Born into slavery in 1818 and sold away from her parents as a child, Bridget “Biddy” Mason went from being a slave owner’s wedding present to his new bride to one of Los Angeles’ wealthiest women, and one of the first African American women to buy and own property in the United States.

As the property of a Mississippi farmer named Robert Smith, Mason cared for Smith’s sickly wife, worked the fields and tended the farm’s livestock. With no formal education, she gradually learned about herbal medicine and midwifery from older enslaved women. She also gave birth to three daughters — Ellen, Ann and Harriet, believed to have been fathered by Smith.

Mormon migration

Always believing the grass was greener, Smith spent his life looking for richer farmland and a better life. When Mormon missionaries came to Mississippi seeking converts to create a new community in the Salt Lake Valley, Smith and his wife joined the faith, becoming part of the Mormon migration in 1847.

Mason, along with others in Smith’s “family,” was compelled to join the trek. The 2,000-mile journey took seven months. She walked most of the way, responsible for setting up and breaking camp, herding cattle, cooking meals and serving as midwife while caring for her three young daughters, the baby strapped to her back. Three years later, the 1850 United States Federal Census of Slave Inhabitants in Deseret County, Utah, showed Biddy, along with her three daughters, as one of 10 enslaved people owned by Robert M. Smith.

On to California

But life was harsh in Utah. So when Brigham Young asked for volunteers to establish a Mormon outpost in Southern California in 1851, Smith uprooted his household yet again to travel across the desert to the new state of California, settling in San Bernardino while ignoring Brigham Young’s warning that slavery was illegal in California.

There, Mason met and befriended a group of formerly-enslaved African Americans including Robert Owens, the local livery stable owner. Mason had no way of knowing California had adopted a constitution stating “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated” there. But the Owens family knew, and they urged her to legally challenge her slave status.

Meanwhile, as tensions built between North and South, Smith feared his human chattel would be seized, and made plans to take Mason, her daughters and his community of enslaved people to an isolated canyon in Santa Monica until they could move to Texas, a slave state.

But Mason’s friends — including one of the Owens’ sons who was courting Mason’s 17-year-old daughter — weren’t having it, and alerted the Los Angeles County Sheriff that Smith was holding enslaved people against the law. The sheriff and his posse apprehended Smith’s wagon train armed with a writ of habeas corpus, ordering him to court for “persuading and enticing and seducing persons of color to go out of the state of California,” and taking Mason and the rest of Smith’s slaves into protective custody.

Free at last

In 1856, U.S. District Judge Benjamin Hays presided as Smith claimed Mason and 14 others he kept in the canyon were family members who voluntarily offered to go to Texas. As a black woman, Mason could not testify against a white man in court. So Judge Hays invited her into chambers, where she gave an entirely different account. She told the judge she was fearful of the trip, despite Smith having assured her she would be just as free in Texas as she was in California.

When Judge Hays explained that California law prevented her minor children being taken to a slave state, Mason — herself having been forcibly removed from her parents, replied, “I do not want to be separated from my children, and do not in such case wish to go.” Hays promptly ruled in favor of Mason and confirmed “all of the said persons of color are entitled to their freedom and are free forever.”

After spending five years enslaved in a free state, freedom wasn’t the only thing Biddy Mason gained that day. Born into slavery, she never had a proper surname. Once free, she chose the name Mason — the middle name of Amasa Lyman, a Morman who was mayor of San Bernardino, and whose family Biddy had come to know well.

Nurse and midwife

Free at last, Mason moved with her children into the Owens’ home. It was through them she met Dr. John Griffin, one of the first formally-trained doctors in Southern California, known as the “Father of East Los Angeles.” Impressed with her nursing skills, he hired her to work with him as nurse and midwife for $2.50 a day, a good wage for a black woman at the time. Over the course of her life, Mason delivered hundreds of Los Angeles babies. “Aunt Biddy,” as she became known to everyone, was often seen carrying her big black bag holding not just the tools of her trade, but the precious papers Judge Hays had given her affirming her freedom.

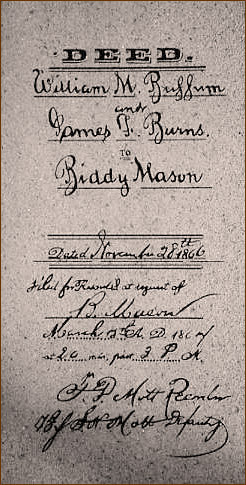

After 10 years, she had saved $250, which the Owens family and Dr. Griffin encouraged her to invest in real estate. And so, in 1866, at age 48, Biddy Mason bought a lot on Spring Street, outside the tiny outpost of Los Angeles. Newly plotted on what was called a “Map of the Plains,” her daughter recalled there was “a ditch of water on the place and a willow fence running around the plot” of land. It was there Mason built a simple clapboard house she would own until her death.

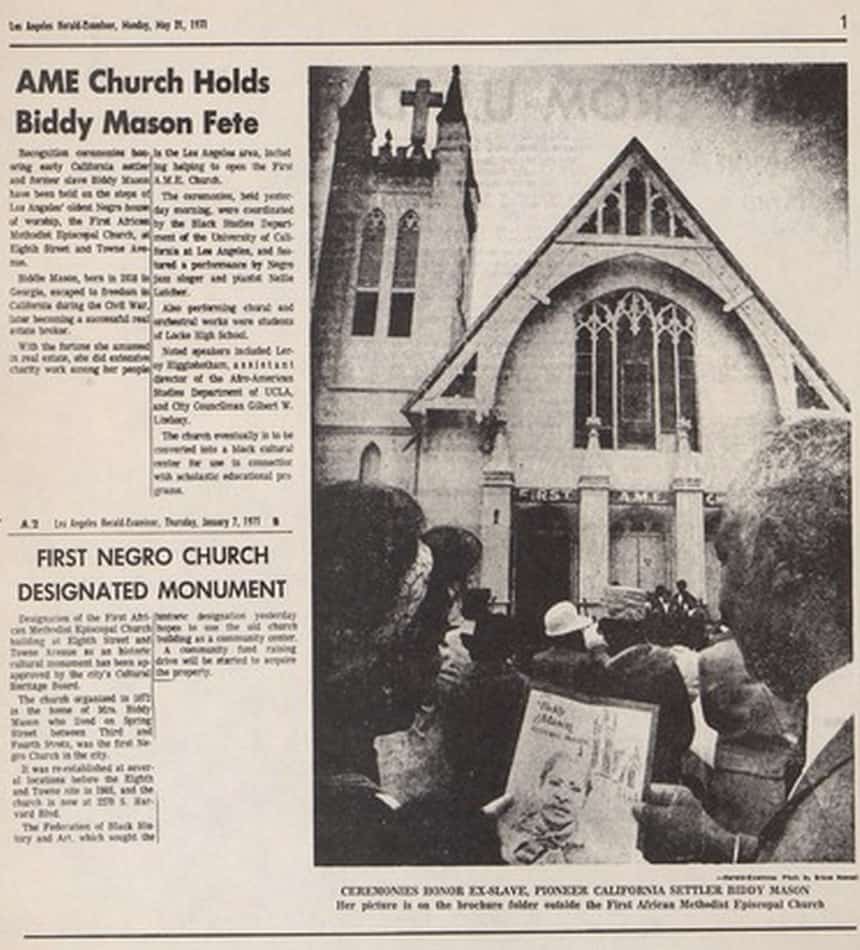

First African Methodist Episcopal Church

Mason always told her children that simple homestead “must never be sold” so they would always have a home of their own. But, as it turned out, that home became so much more. It was a place where stranded or needy settlers found refuge; a daycare center for working mothers; and where the First African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in 1872, and continued to meet until they could erect their own building.

Through the years, Mason continued to invest; but as her fortunes grew, she always made it a point to give back to the community. According to the Los Angeles Times, she was a frequent visitor to the jail that had once given her refuge. She paid taxes and all expenses on church property to hold it for her neighbors. And when Los Angeles flooded in the early 1880s, she gave the nearby grocer an open order so that every family left homeless could be supplied with groceries while she paid the bill. She also founded an elementary school for black children.

Biddy Mason eventually left Dr. Griffin to set up her own business, continuing to serve the community as a midwife. But she was also a shrewd businesswoman, buying and selling property as the city of Los Angeles grew and developed around her and signing every deed with her signature “X”, since she had never learned to read or write. By the early 1890s, the main financial district of Los Angeles was just one block from Mason’s property.

Died in 1891

In January of 1891, at the age of 73, Bridget “Biddy” Mason died at her beloved homestead, leaving her heirs a fortune estimated at $3 million and a legacy of perseverance, compassion, generosity and triumph. At the time of her death, she was one of the wealthiest women in Los Angeles. Yet, for reasons unknown, she was buried in an unmarked grave in the city’s Evergreen Cemetery.

As so often happens, her estate became the focus of a bitter family feud. Once settled, what was known as the “Mason Block” was put into the hands of her grandson, who became the wealthiest black man in Los Angeles County. To their credit, the family was able to hold onto Mason’s cherished “first homestead” until the Great Depression.

Biddy Mason’s memory was eventually reclaimed by the city of Los Angeles. In 1988, Tom Brady, the city’s first black mayor, and several thousand members of the church she helped found, held a graveside ceremony at which her grave was officially marked with a stone. That same year, the California Afro-American Museum included her in their “Black Angelenos” exhibit.

Memorial Park

Today, Biddy Mason Memorial Park occupies the location of her original homestead, purchased for $250 in 1866. Designed by architects Katherine Spitz and Pamela Burton, Biddy Mason Time and Place is an 80-foot-long, poured concrete wall by artist Sheila Levrant de Bretteville. It tells Mason’s story through a timeline illustrated by impressions like agave leaves, wagon wheels and a midwife’s bag, along with text and images of survey maps of early Los Angeles as well as Mason’s emancipation papers. Beginning with “Biddy Mason born a slave,” it concludes with “Los Angeles mourns and reveres Grandma Mason.”

But the best, and most fitting, memorial to Bridget “Biddy” Mason are her own words as recalled by her great-granddaughter many years after her death:

“If you hold your hand closed, nothing good can come of it. The open hand is blessed, for it gives abundance, even as it receives.”

This is true story is very beautiful and show how you can come from nothing to the Top most. May Biddy Mason Soul Rest in Peace with the Almighty God.