Blanche Stuart Scott couldn’t stand the thought of “being a nobody and a nothing in New York’s millions.” So this only child, spoiled by wealthy parents and described as stubborn, adventurous, competitive and fiercely determined, became somebody, racking up a slew of firsts along the way. Unfortunately, some of those firsts weren’t. Some were more like close, but no cigar.

Born in Rochester, NY, Scott never ‘fessed up to her age, telling the Associated Press in 1928, “Don’t ask how old I am – I’ve been 29 for years.” But reviews of Rochester census data, the Social Security Death Index and Rochester cemetery records seem to indicate she was born circa 1884/85.

Her father made his fortune making and selling patent medicines, including something called Scott’s Arabian Paste, or hoof paste, advertised in the 1890s as a miracle cure for “soreness and inflammation no matter where found in Man or Beast, including boils, cuts, rope burns, contracted feet, cracked heels, thrush, and caked udder in the cow.” In the Scott family, hyperbole and exaggerated claims may have come naturally.

Rambunctious and impetuous, young Blanche Scott loved ice skating, exploring the wilds of Rochester and outdoing the neighborhood boys with tricks on her bicycle. She also had an insatiable curiosity about machines, including the new-fangled horseless carriages just beginning to hit the streets. One anecdote claims she crashed so many bikes her father refused to buy her another. Instead, when he bought himself a new 1-cylinder car, he taught Blanche how to drive at age 13.

13 Year-Old Automotive Joy Rider

At a time when there were no age restrictions or license requirement for drivers, when speed limits were about 2-8 miles per hour, and lead-footed drivers were called “Scorchers,” neighbors were by turns amused and horrified to see a tiny red-haired girl joy riding through Rochester’s streets. Many accounts claim Mr. Scott’s new car was a Cadillac. And if Scott was born in 1884/85, she would have been 13 in 1897/88. Turns out Cadillac’s first 1-cylinder horseless carriage models, the Runabout and Tonneau, didn’t hit America’s streets until 1902.

Her father died in 1903, leaving his widow to raise an out-of-control daughter. Her solution was to pack Blanche off to a series of fancy finishing schools in hopes they would soften the rough edges and return a more ladylike young woman. After graduating from the Misses School for Girls in Rochester, Howard Seminary in Massachusetts and the Fort Edward Collegiate Institute in New York, Scott moved to New York City, outwardly more demure, but inside every bit as daring. She described herself during this period as “a screwball … a cocky kid of 18, and the whole thing was a lark.”

Automotive Adventure

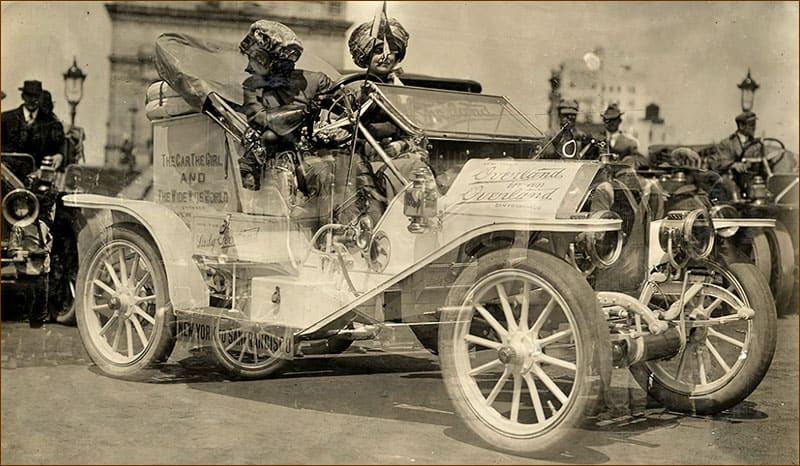

In 1910, the Willys-Overland Motor Company sponsored a cross-country automobile trip from New York to San Francisco to promote their 25-hp Model 38 Overland. Blanche Scott remembered reading about two men, Dwight Huss and Percy McGargle, who made the first documented transcontinental automobile journey five years earlier. She figured if two men could do it, so could she. So she wrote the company’s president with an offer he couldn’t refuse — she would drive his car across America as a publicity stunt to set a record for women. Recognizing a publicity goldmine when he saw one, he agreed. An ad in the Syracuse Post Standard described the $1,000 Overland as “so simple and trouble proof that even a novice can successfully operate it from the very start. All complex mechanisms have been eliminated in this car. It is the ideal woman’s car.”

In May 1910, a spiffy silver and blue car with neatly painted letters proclaiming it the “Lady-Overland” left New York City with its slogan, “The Car, The Girl and the Wide, Wide World,” lettered on the door. Scott was accompanied by newspaperwoman Gertrude Buffington Phillips, who wouldn’t drive but would file reports from the road. They arrived in San Francisco in July 1910 after covering over 5,000 miles in 67 days spent zigzagging between Willys dealers.

Along the way, they got lost on uncharted roads, fixed flats, dodged potholes and gophers, and scared horses and cows half to death as they motored through America’s small towns. Scott told of the hardships she overcame tackling Death Valley as Jacob Murdock had done in 1908. Problem was, some reports indicate she crossed into California at Lake Tahoe, much farther north.

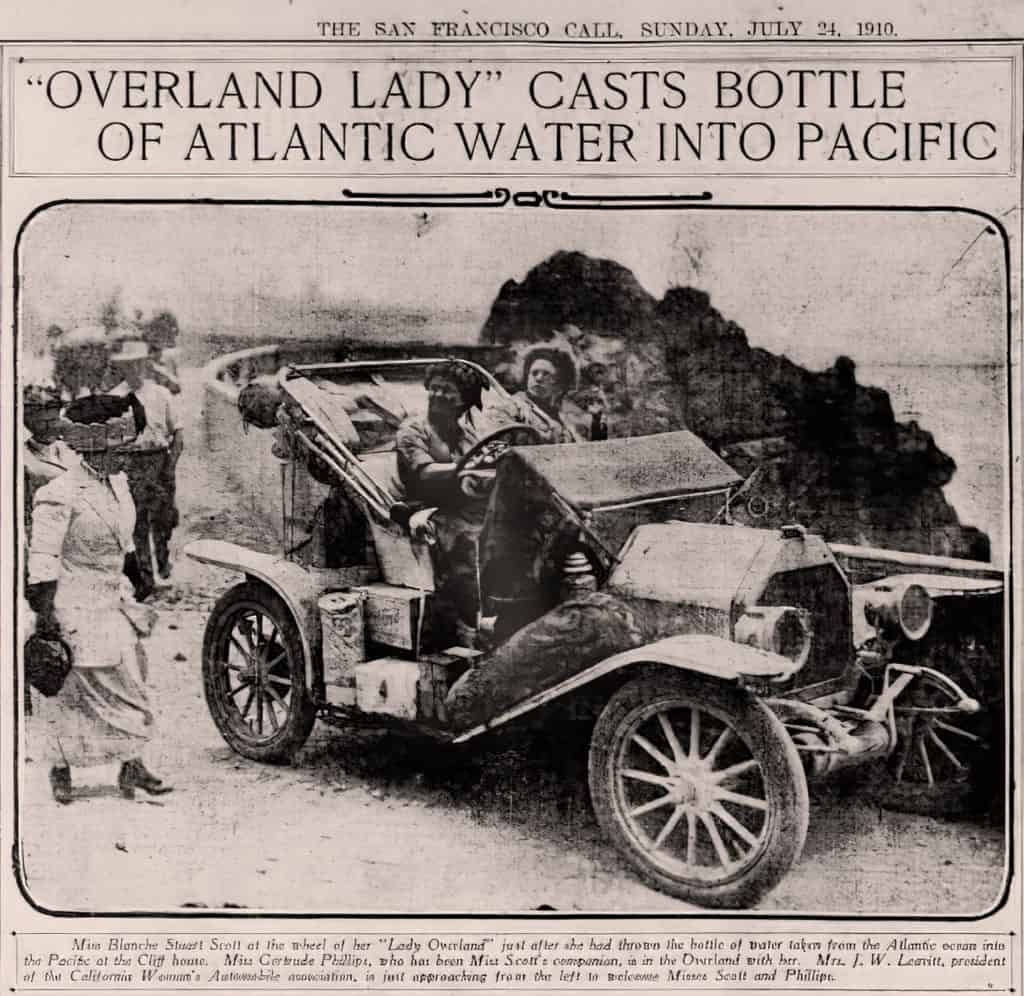

They were met in San Francisco by a band and nearly 1,000 automobiles lining Market Street. Scott continued to the Cliff House where, according to the San Francisco Call, she “tossed a bottle of Atlantic Ocean water into the Pacific.”

Blanche Stuart Scott had finally become somebody when she was lauded as the first woman to drive coast to coast across America. Except she wasn’t. That first actually belongs to Alice Huyler Ramsey, who set the record a year earlier in 1909.

But the cross-country trip was a first for Scott for another reason. Just outside Dayton, OH, she spotted an airplane, part of an exhibition sponsored by Dayton’s Wright School, for the first time. Before she reached Indianapolis, the spark was lit for what would be her next great adventure. As she later recalled, “I thought these people flying were idiots, not realizing I’d be doing the same thing three weeks later.”

Bogus Flight Report

While she was in California, an Associated Press reporter told Scott the pilot of a French-made Farman biplane wanted to take her aloft. Against her better judgment, she agreed. But the plane crashed before she could make the flight, damaging the aircraft but leaving the pilot uninjured. The reporter, however, had already filed a story that ran in the New York Times on August 7, 1910: “Flight Winds Up Auto Trip” told of a Vassar College student (no enrollment records exist for Scott, according to Barbara Hoeft of Vassar’s Alumnae House) who had driven across the continent on a dare before making an ascent in a biplane, where she and the pilot flew a mile and a quarter over several minutes. To save his job, the reporter and Scott agreed to keep quiet about the crash and the ride that never happened. In what would become a pattern, Scott’s first flight was a fabrication.

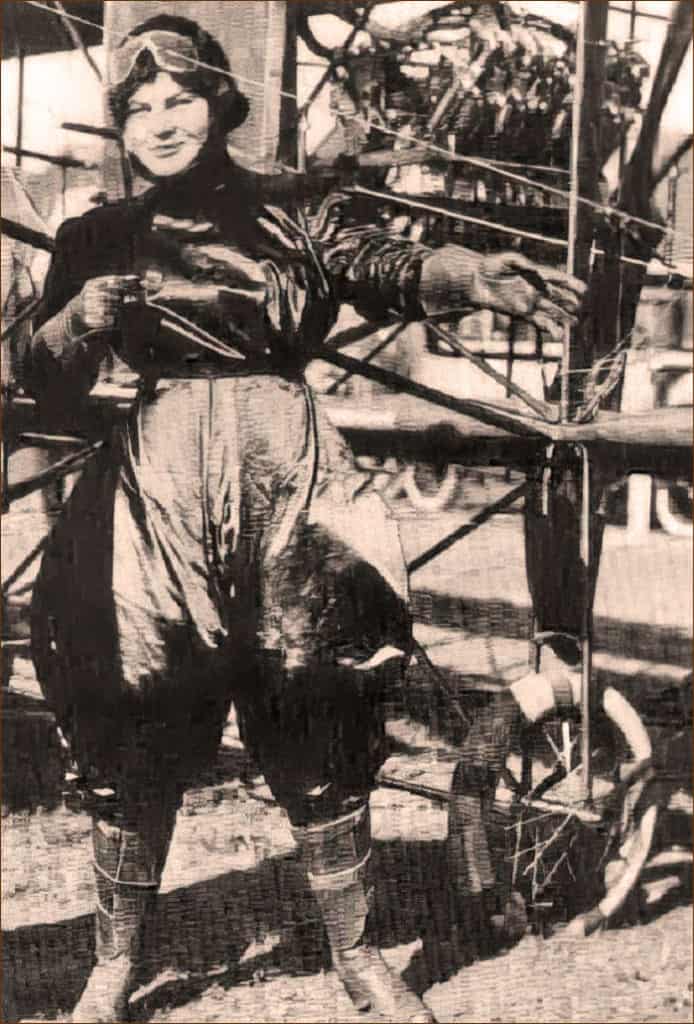

The spate of publicity surrounding Scott’s road trip caught the eye of a press agent for Glenn Curtiss’ exhibition team, who approached her with the idea of joining this exciting new form of public entertainment. Against his better judgment, Curtiss (considered the founder of America’s aircraft industry) offered Scott flying lessons in Hammondsport, NY, making her the first and only woman he ever taught.

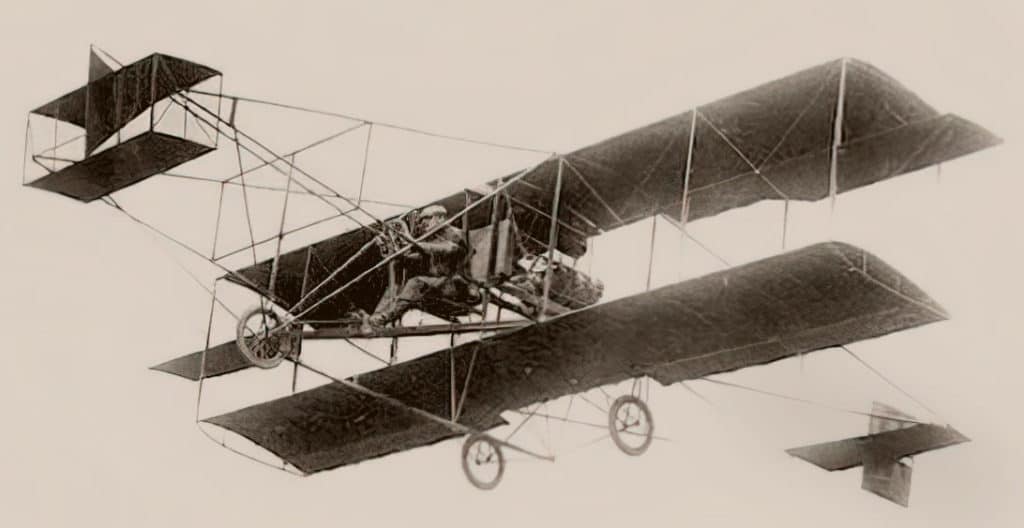

She learned to fly in a one-seat plane called a Curtiss Pusher. As she described it, Curtiss stood outside the craft while Scott, wearing custom-made bloomers filled with three petticoats, sat in “an undertaker’s chair” in front of “a motor that sounded like a whirling bolt of a dishpan.” She recalled, “In those days they didn’t take you up in the air to teach you. They told you this and that. You got in. They waved or kissed you good-bye and trusted to luck you’d get back.”

She began by learning how to taxi up and down the field. A reluctant Curtiss, fearful that a mishap with a female pupil would create negative press, had placed a block of wood called a limiter behind the throttle pedal to keep the plane from gaining enough speed to become airborne. But a sudden gust of wind came up behind Scott, lifting the box-kite-like biplane to an altitude of 40 feet in what might best be called an extended hop before she landed safely.

But that unplanned hop on September 6, 1910, was enough for the Early Birds of Aviation (their website describes an organization of pioneer aviators whose mission was to preserve aviation history, advance interest in aeronautics and enjoy good fellowship) to credit Blanche Scott with being America’s first woman to pilot and solo an airplane.

Not Quite First

Ten days later, a woman named Bessica Raiche made her first solo flight in a biplane she and her husband built. She took off and skimmed over the airfield a few feet above ground for about a mile before running into a depression which jammed the nose of her plane into the ground and threw her out, the lightweight plane falling on top of her. Luckily, she emerged shaken but uninjured.

While Scott was accidentally lifted into the air by a gust of wind, Raiche took flight after careful planning, with enough eyewitnesses to document her flight of almost a mile. As a result, the Aeronautical Society of America declared her the first woman aviator in America, awarding her its diamond-studded gold medal at a dinner in her honor.

That same year, Scott became a professional pilot when she debuted as a member of the Curtiss exhibition team at an air meet in Fort Wayne, IN, legitimately marking the first professional appearance of a female aviator witnessed by thousands.

“Tomboy of the Air”

Nicknamed the “Tomboy of the Air,” she became an accomplished stunt pilot known for flying upside down and performing heart-stopping “death dives” from 4,000 feet, suddenly pulling up only 200 feet from the ground, earning up to $5,000 a week.

It was Spring 1911 when Scott joined Thomas Baldwin’s exhibition group, flying a new aircraft — the first plane built with a steel framework, called the Red Devil. She was only supposed to fly over the airport when, before realizing it, she had been in the air for nearly an hour. When a large crowd, worried that she was missing or had crashed, greeted her upon landing, a reporter asked, “Do you realize your flight was 30 miles out and 30 miles back?” Scott’s answer: “I needed to fly, so I flew.”

Next morning, New York papers ran headlines describing how Scott had accomplished the longest flight ever made by a female in yet another first for the woman determined to become somebody.

Another Not Quite First

But, once again, it was a case of mistaken firsts. A year earlier, on December 31, 1910, Belgian-born Helene Dutrieu made the first nonstop flight of 104 miles in two hours and 41 minutes, earning the Femina Cup, awarded to female pilots by the French women’s magazine, Femina. By the time Scott was granted her dubious honor in 1911, Dutrieu had won for a second time.

The following year, Scott was flying for Glenn Martin, whose 1912 aircraft company went through a series of mergers before becoming Lockheed Martin. In that capacity, she became the first female test pilot, flying prototype aircraft so designers could work out the bugs before final blueprints were made.

The next year found her with yet another exhibition team. But a crash on Memorial Day in 1913 resulted in serious injuries requiring a year-long recuperation. She had already witnessed fellow aviator Harriet Quimby’s death and had now had her own serious accident. And she was unnerved by the public’s macabre fascination with air crashes after overhearing one disappointed spectator remark, “It wasn’t as exciting as I had expected. Nobody got killed.” Blanche Stuart Scott retired from flying in 1916.

From Airborne to Airwaves

After hanging up her leather aviator’s helmet and goggles for the last time, Scott headed to Hollywood where, four years earlier, she had landed roles in the first silent movies made about flying, “An Aviator’s Success” and “The Aviator and the Autoist Race for a Bride.”

A 1928 Associated Press interview described the “first woman pilot in the US to solo still using the airways — as a radio station’s program director. To look at her, you’d never know she was a pioneer barnstormer. She has blonde curls, twinkling eyes, the attractive figure of a college girl and the vivacity of a successful businesswoman.” During the 1930s, Scott worked for RKO, Universal and Warner Brothers studios, writing comedies, stage treatments and children’s stories while writing, producing and hosting “Rambles with Roberta,” a series of radio shows airing in California and New York.

Despite having her feet firmly on the ground, Scott’s love of flying still ran deep. So in September of 1948, when renowned US Air Force pilot and flying ace Chuck Yeager offered her a 600-mph ride in the passenger seat of a TF-80C two-seat jet trainer, she jumped at the chance. Knowing her history as a stunt pilot, Yeager made sure to treat her to some snap rolls and a 14,000-foot dive.

Not the First Jet Flight by a Female

Scott and the media promptly trumpeted hers as the first flight in a jet by an American woman. Unfortunately, it was another dubious claim. Ann G. Baumgartner Carl was an American aviator and the first American woman to fly a US Air Force jet when she flew the Bell YP-50A jet fighter at Wright Field as a test pilot during World War II.

In the 1950s, firmly believing “retirement is a crime,” Blanche Scott went back to Dayton, OH, where her fascination with flight was born. She was hired by the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Base as a special consultant, a position she held until 1956, traveling extensively to acquire priceless early aviation materials for its collection. During that time, she collected $1.25 million worth of early aviation artifacts, describing herself as “one of the world’s best chiselers.”

Death and Legacy

Blanche Scott died in January of 1970 in her hometown of Rochester, NY. At her request, she was cremated, her ashes buried at Rochester’s Riverside Cemetery. And while most sources say she was 84 at the time of her death, even her tombstone is iffy about her true age as it bears a birthdate that’s off by five years, putting her closer to 90 at the time of her death.

An adventurous, daring woman who was flying when airplanes were first being invented, she lived long enough to see Neil Armstrong walk on the moon. And despite some questionable firsts, she never had to worry about being “a nobody and a nothing in New York’s millions” or anywhere else. She was a true pioneer in what was the new, dangerous and male-dominated aviation industry, taking to the air long before women on the ground had the right to vote.

She was honored by the Aeronautics Association of the United States in 1953 and the Antique Airplane Association in 1960. In 1980, 10 years after her death and 70 years after that first accidental extended hop, the US Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp recognizing her achievements in aviation. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2005. And if you visit the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, you’ll find a portrait of Blanche Scott, placed in 1950 to honor her.