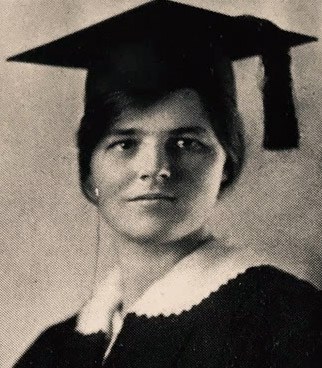

Diminutive, quiet, and bespectacled, it was Mary Sears’ nature to let her research and prodigious body of work speak louder than any commendations or public recognition that came her way. Still, few would argue that she changed the course of oceanographic history, contributed to its growth as an internationally recognized science and, along the way, helped win World War II.

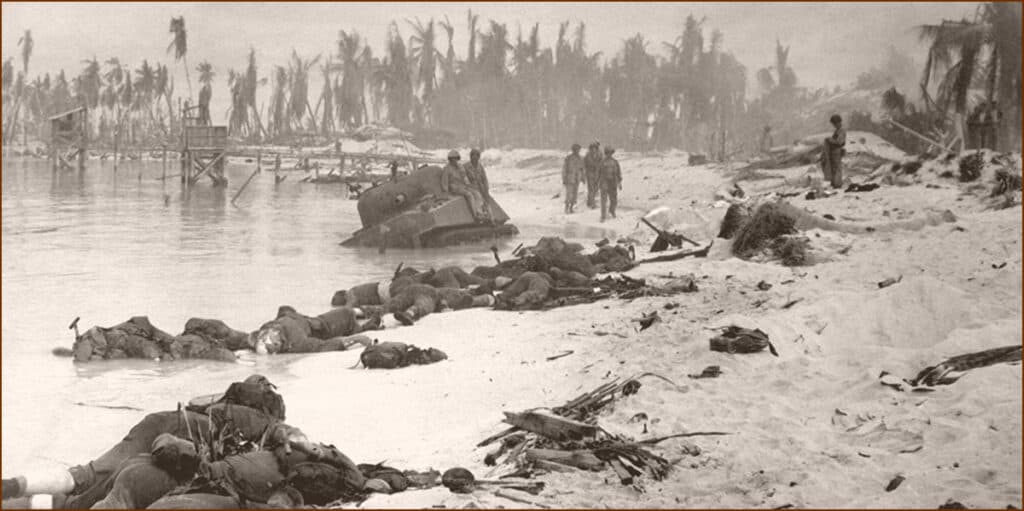

The unassuming scientist would initially be rejected when she tried to join the U.S. Naval Women’s Reserves (WAVES) at the outbreak of World War II. But her expertise suddenly became vital as the conflict exploded across the Pacific theater and the Battle of Tarawa demonstrated deadly weaknesses in the Navy’s understanding of tidal dynamics and coastal infrastructure as they related to massive amphibious assaults. In a turnabout that put her career on a new course, the Navy brought Mary Sears in to help solve the problem.

~ ~ ~

Mary Sears was born in 1905 in Wayland, Massachusetts. She would disappear for hours, exploring the nearby bogs, collecting frogs and turtles for her large terrarium. Her mother died from polio at age 28 in 1911 when Mary was just six years old. Soon after, her bereft father moved to Europe, leaving his young children in the care of live-in nannies, relatives, and friends.

One of those friends was Sophie Bennett, a teacher at Boston’s highly competitive Winsor School, a private, college-prep day school for girls. Founded in 1886, Winsor had long been among the world’s top schools for its success in preparing young women to enter America’s finest universities; in 2018 it was still ranked the best all-girls school in the United States. Sears enrolled at Winsor as a fifth-grade student in 1915. Later that year, her father returned from Europe, began dating Bennett, and married her several years later.

Influential Teacher

Sears graduated from Winsor in 1923 and enrolled in Radcliffe College. She had every intention of studying Ancient Greek until she took a biology course taught by zoologist George H. Parker and changed her field of study. Born in Philadelphia, Parker was part of a group of scientists at the Academy of Natural Sciences that included distinguished paleontologist Dr. Joseph Leidy.

Four years later, Sears graduated magna cum laude with a degree in zoology as a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. She remained at Radcliffe for graduate school, earning her master’s degree in 1929 and her Ph.D. in zoology in 1933. Grounded in science, and gifted with enthusiasm, curiosity, and a brilliant mind, she wrote her Ph.D. thesis on melanophores — cells that give many organisms, including her childhood favorite, box turtles, their color patterns. Her advisor was Henry Bigelow, a founder and first director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

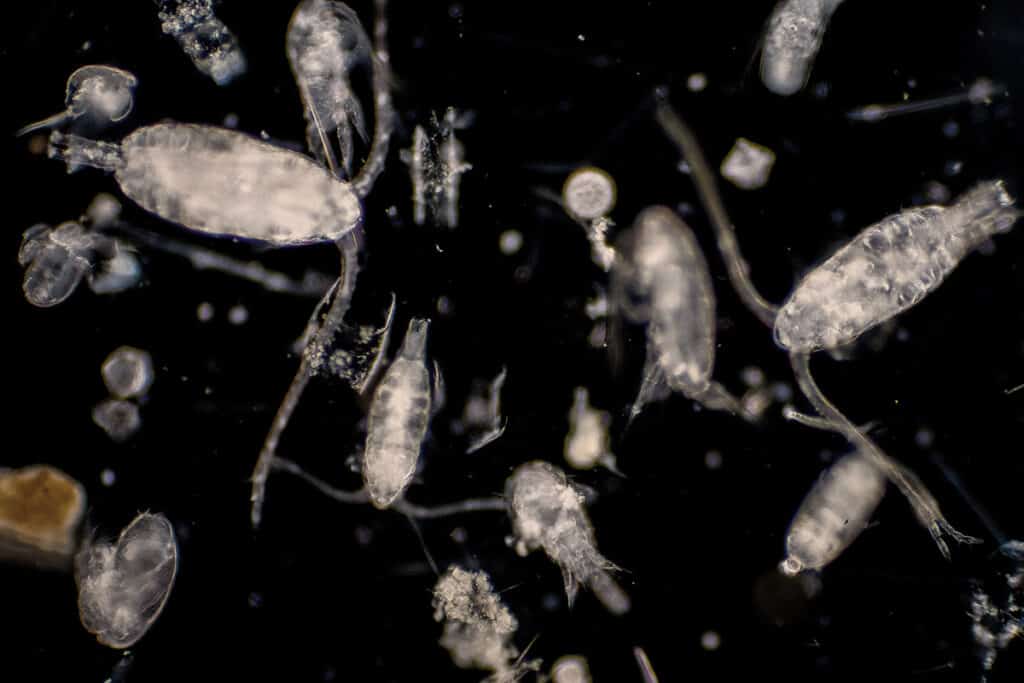

In 1932, armed with her doctorate, Sears spent her summers studying plankton at WHOI. From the Greek word planktos, meaning “drifter,” plankton are microscopic organisms that drift in the water, going wherever the tides and currents take them. Tiny and aimless as they are, they provide the foundation of fresh- and seawater food pyramids. Her appointment as a year-round planktonologist at Woods Hole came in 1940.

Zooplankton Expert

She was present at WHOI for discussions leading up to the acquisition of its first research vessels, the 142-foot Atlantis and the 40-foot Asterias, as well as its first laboratory, later named the Bigelow Laboratory for her mentor. Working with him, Sears published papers on zooplankton populations from Cape Cod to the Chesapeake Bay as well as plankton in the Gulf of Maine, between Cape Cod and Nova Scotia, comprising the entire coastline.

As you can imagine, for an oceanographer, going to sea was a necessity. After all, where would Jacques Cousteau have been without his research vessel Calypso? There was just one problem: Mary Sears was a woman. And because of the time-honored belief that women aboard ships would distract the crew and provoke the wrath of the sea, she was banned from the WHOI’s research ships.

But in 1941, ornithologist William Vogt reached out to Sears, a member of Wellesley’s Committee on Inter-American Cultural and Artistic Relations. Author Charles Mann described Vogt as “the intellectual father of the modern environmental movement.” He needed her help analyzing plankton for clues as to why the birds off Peru’s coastal islands who fueled that country’s guano industry were dying in massive numbers. Sailing the Peruvian islands with Vogt and an all-male crew for nine months, Sears did not distract the men; nor did she provoke the wrath of the sea. She was still at sea when she learned about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

As World War II Starts

When she returned to Woods Hole in early 1942, it was not the same place she had left. War efforts had transformed WHOI. The harborside lab was fenced off with barbed wire; wooden guard shacks had popped up; and the popular aquarium and seal pool were closed to the public until further notice. Sears joined a group researching barnacles and underwater vegetation that accumulated on ship hulls. But she couldn’t help noticing the halls became less crowded as more men left to join the Navy. Full of patriotic fervor, Mary Sears wanted to do her part.

Despite her age (nearly 40), she went to a nearby recruiting station to sign up for the WAVES, the newly organized all-female component of the U.S. Naval Reserves, only to be turned down due to a long-past diagnosis of arthritis secondary to a Strep infection. She might have spent the war years stuck in the WHOI lab but for the intervention of U.S. Naval Lt. Roger Revelle, an oceanographer from San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography serving in the Navy’s Bureau of Ships. Revelle came to WHOI hoping to recruit one of its scientists to serve at the Navy’s Hydrographic Office (known as Hydro). As luck would have it, the only scientist the WHOI director was willing to part with — the only one he considered nonessential to his wartime research — was Mary Sears.

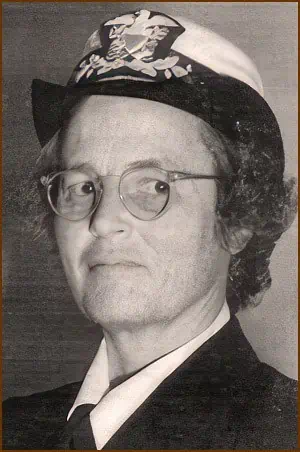

Lieutenant Sears

After Revelle’s visit, Sears reapplied for a commission in the WAVES, knowing she would not be accepted without a medical waiver. Again, she was in luck. Admiral George Bryan, the officer in charge of Hydro, was also a Woods Hole trustee who knew about Sears’ expertise and her dogged work ethic. He also knew she was familiar with the development of something called a bathythermograph — an instrument that could help ships evade and attack the enemy. And while Bryan didn’t know all the details of this new top-secret innovation, he understood the impact its new technology could have on Naval war strategy. Admiral Bryan personally wrote a recommendation for Sears’ commission. In January of 1943 she received the long-awaited waiver — and the chance to serve her country more directly.

That spring, after completing two months of intensive training at the Naval Midshipmen’s School at Mount Holyoke College (one of only two locations where women could train to become naval officers), Sears was commissioned as a lieutenant (junior grade) to head up the Navy’s new Oceanographic Unit (OU) in Maryland — a place considered understaffed, poorly supplied, and home to research considered menial by most scientists. But Sears didn’t miss a beat. She began producing oceanographic charts in advance of planned amphibious assaults throughout the Pacific Theater. Within a month, she had published papers on sea drift to better help the Navy find crews and debris after their ships sank or planes crashed.

Sears wasted no time assembling a team most people might find eccentric. They included Fenner Chace, Jr., an authority on crustaceans and skilled maker of handkerchief-sized cloth survival maps that could withstand the elements and be easily concealed. Mary Grier was considered the most knowledgeable oceanographic librarian in America. It was said that if anything, anywhere, in any language, had been published about the North Pacific, Mary Grier knew about it and knew where to find it. Then there was Dora Henry, a.k.a. “The Barnacle Lady.” She was an acknowledged expert in something Mary Sears had researched on her return to WHOI in 1942: barnacles and their buildup on ship hulls known as “bottom fouling” that slowed ships down and decreased their fuel efficiency during long cruises.

Battle of Tarawa’s Heavy Losses

Then came November 1943, when America conducted its first offensive in the critical Pacific Theater — the Battle of Tarawa. Admiral Chester Nimitz’s formidable fleet shelled the atoll, pitting 18,000 Marines against 4,000 Japanese defenders. But U.S. intelligence proved outdated and faulty; tides were at their lowest; the water was unexpectedly shallow; and landing craft grounded far offshore and became stranded or submerged on coral outcrops. With rifles held high, the Marines slogged ashore and into a deadly fusillade that left 3,500 troops dead or wounded. While the U.S. press was quick to chalk up the horrific loss to Japan’s fierce resistance, top brass kept its inept reconnaissance and outdated data top secret.

For the first time, the U.S. Navy understood it had to study the oceans in very different ways to produce the intelligence they desperately needed if they were to avert another Tarawa. Lucky for them, Mary Sears — a woman they had initially rejected — and her team were ready.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff expanded Sears’ small unit to 400 personnel after she explained, “given good weather data, one could forecast wave conditions and surf height…for the obvious advantage of amphibious landing operations.” Her unit collected raw data from Allied vessels and shore stations, processed it, and passed it along to field units as ordered. Sears also had relevant Japanese oceanographic material published in the 1930s translated into English.

Sinking Ships With Oceanic Data

Her unit’s data supported the underwater offensive that crippled Japanese warships and its merchant fleet. Since submarines ran in a dark, silent column of water, analyzing the mix of currents, salinity, and density aided navigation and, more importantly, helped evade the enemy.

Admiral Nimitz’s strategy was to neutralize most of the Japanese-held islands in the central Pacific by nonstop bombing, restricting landings to key strongholds. But since only President Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs knew the targets in advance, Sears had to supply appropriate intelligence for all possible targets. By the time Nimitz set his sights on Iwo Jima, the deadly errors of Tarawa would not be repeated.

In October 1945, three months after V-J Day, Sears’ Oceanographic Unit became the Oceanographic Division, which she led. Cited for “accomplishments of great value to the Armed Forces of the United States,” she was promoted to lieutenant commander. She worked as a Navy oceanographer until leaving active duty in June 1946, when Admiral Nimitz issued a commendation thanking her for the U.S. Navy’s having reliable oceanographic data.

Post-War Senior Scientist

After spending a year in Denmark studying siphonophores (predators like the Portuguese Man O’War who use their stinging tentacles to lure their prey), Sears returned to Woods Hole in 1947 as Senior Scientist in the Biology Department, a position she held until retiring in 1970. She was named a Scientist Emeritus in 1978.

As you might expect, Mary Sears’ list of honors and awards is as long as your arm. She was elected a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1960 and a Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1964. To mark her 80th birthday in 1985, the highly-esteemed journal Deep-Sea Research, of which she was founding editor, dedicated an issue to her.

She received honorary degrees from Mount Holyoke College and Southeastern Massachusetts University (now the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth). Radcliffe honored her in 1992 with its Alumnae Recognition Award, given to “women whose lives and spirits exemplify the value of a liberal arts education.” And she was named Woman of the Year by the Falmouth Business and Professional Women’s Organization in 1996 for her many professional and community contributions.

New Navy Ship, The Mary Sears

When it came to military honors, Sears was awarded the American Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, and Naval Reserve Medal. In 2000 the US Navy recognized her service with the launch of a 300-foot research vessel named for her; the Oceanographic Survey Ship USNS Mary Sears is one of seven research vessels operating today. She was also recognized in 1996 at the retirement of the Research Vessel Atlantis II, which she had christened in 1962.

Two awards now bear her name. The Oceanography Society presents the Mary Sears Medal for extraordinary accomplishments in biological oceanography, marine biology, or marine ecology. And in 1994 the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution established the Mary Sears Women Pioneers in Oceanography Award, recognizing long-term, life achievement and impact, with special consideration given to those candidates who have shown leadership through mentoring junior scientists, technicians, or students.

Finally, in 2022, author Catherine Musemeche wrote the excellent Lethal Tides (Harper Collins Publishers), the story of Mary Sears and the marine scientists who helped win World War II.

Pushing Past Barriers

Late in her life, an aspiring female oceanographer asked Sears what barriers she had faced in her career. Without missing a beat, Sears replied, “Well, in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, the ladies’ room was on the fourth floor.” But she went on to say that in science, as in the war, “We worked so hard for a common cause I was hardly aware of any barriers.” Mary Sears counseled every young female scientist she met to do the job, stand firm, and simply refuse to be pushed aside.

Mary Sears died at her home in Woods Hole in September of 1997 at the age of 92 following a brief illness. The WHOI cited her as one of its first staff members and a guiding force in its development.

Following a private funeral, she was cremated. As somehow befits the character of the shy, bespectacled, down-to-earth scientist who always wanted her research and body of work to speak louder than any public recognition she might receive, Mary Sears’ ashes were buried in the Woods Hole Village Cemetery beneath a beautifully weathered, lichen-spotted stone bearing a plaque that reads simply:

Mary Sears

1905-1997