Think of a song born of wind bubbles, visual swoops, clouds and something called a “wobbulator.” Hummable, with a strong beat, but totally unique. One of the most-heard and instantly recognizable pieces of music today. Give up? It’s the theme for the popular British TV sci-fi series Doctor Who; and it was created by Delia Derbyshire, referred to as the “unsung hero of British electronic music.”

Mathematics and Music

Born in Coventry, England, her family moved to the safety of Lancashire, some 125 miles north, after World War II’s 1940 Coventry Blitz. An extremely bright child, Delia could read and write by age four. She was accepted at both Oxford and Cambridge, quite a feat for a working-class girl in the 1950s, when just one in 10 students were female. She chose Cambridge after being offered a math scholarship.

Though she loved the precision of mathematics and its sense of structure, she switched to music after her first year, graduating in 1959 with a Bachelor’s degree in math and music. But not music in the traditional sense. Derbyshire was into sound and acoustics. As she put it, “I was always into the theory of sound. The physics teacher refused to teach acoustics, so I studied it myself and did very well. It was always a mixture of mathematics and music.”

From the United Nations to Pink Floyd

Not sure what to do with her degree, Cambridge’s careers office suggested a job working with the deaf, or in underwater depth sounding. Instead, Derbyshire approached Decca Records, only to learn they didn’t hire women to work in their studios. So she did something completely different, working for the United Nations in Geneva, teaching piano and math to the children of diplomats.

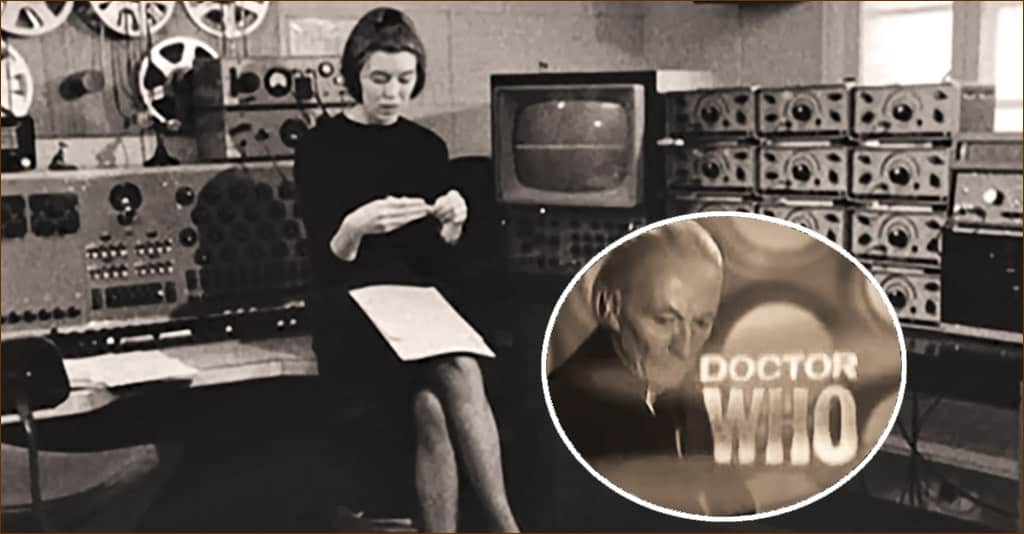

Back in London by late 1960, Derbyshire took a job with the BBC as a trainee assistant studio manager. When she learned about their Radiophonic Workshop, she knew that was the place for her. Its specialty was creating sounds to accompany radio and television broadcasts. By the spring of 1962 she was assigned there and, over the next 11 years, created music and sound for almost 200 radio and TV programs.

She rubbed elbows with musicians like the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, Paul McCartney and George Martin, and members of Pink Floyd, who were frequent visitors. Never starstruck or easily flustered, she impressed them with her knowledge of sound manipulation and disarmed them with her sense of humor and an easy charm.

Ron Grainer and The Doctor

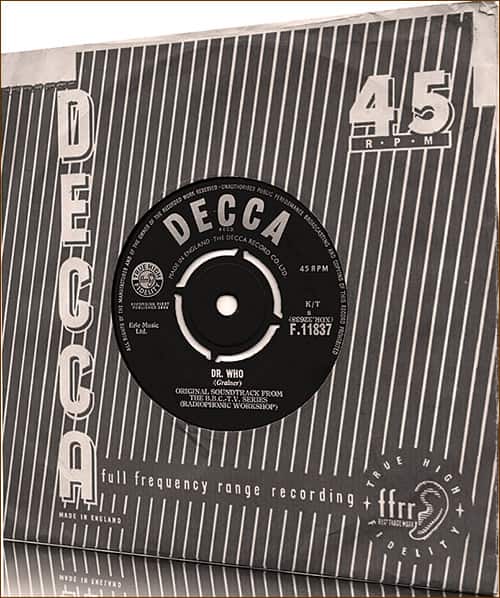

In the summer of 1963, Derbyshire met an Australian composer working for the BBC named Ron Grainer. The result of their meeting, and one of her first works, was the electronic version of a score for the Doctor Who series — one of the first TV themes created and produced completely by electronics.

Grainer wrote the score on a single sheet of paper, including visual titles, swoops, and concepts like wind bubbles and clouds, leaving it to Derbyshire to realize it using electronic sound. With that one page to go on, she worked her magic, piecing together what became one of the most-recognizable pieces of electronic music. In fact, her recording of Grainer’s Doctor Who theme was ranked by music site Pitchfork as the 76th greatest song of the 1960s.

The first time Grainer heard the theme, he was amazed, asking, “Did I really write this?” To which Derbyshire modestly replied, “Most of it!” Grainer petitioned the BBC to give her co-composer credit, but was turned down because of BBC policy: members of the Radiophonic Workshop were to remain anonymous. Derbyshire would not get on-screen credit for her work until Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary special, The Day of the Doctor, airing in November of 2013. But her original version served as Doctor Who’s theme for 17 seasons, from 1963 to 1980.

Birth of the Doctor Who Theme

In 1963, Robert Moog had yet to introduce his synthesizer; and commercial digital recording was a decade away. So Derbyshire worked the old-fashioned way, using a collection of tape recorders for echo and reverberation effects, along with oscillators, amplifiers, noise generators, filters, modulators and mixers to create and manipulate sounds made from everyday objects — bells, bottles, stringed things, clocks, copper hot water cylinders, a broken upright piano; and Derbyshire’s favorite — an old industrial metal lampshade that made a bell-like chime when tapped.

She recorded on analog tape machines with a supply reel on one side and a take-up reel on the other. Each note was hand-crafted, the familiar first notes made by plucking a single bass string. Grainer’s “swoops” came from manually adjusting an oscillator’s pitch to a precisely-timed pattern. Filtered white noise became “clouds” while the wobbulator (one of the oscillators) created “wind bubbles.”

Derbyshire described the process: “There were no musicians; no synthesizers; not even a 2-track or stereo tape machine. It was all mono (single-channel recording). Every part of the song was constructed on 1/4-inch mono tape, inch by inch, using…filtered white noise and something called a wobbulator. Three separate tapes were made, then put into the machines. We stood next to them, counted down, and pushed all three ‘start’ buttons at once, letting the outputs mix together.” The resulting theme song lasted just two minutes and 19 seconds.

Life After Doctor Who

In the mid-’60s, Delia Derbyshire collaborated with experimental and electronic music producers, playing at festivals, producing albums and working on electronic scores and soundtracks for movies and plays. In the early ’70s, she worked odd jobs, first as a radio operator, then in a bookstore and an art gallery. Then, in 1975, the music stopped. Or so it seemed.

After a failed marriage, she met her partner for the rest of her life. He summed up Derbyshire’s post-BBC years, often perceived as a complete withdrawal from music: “In private, she never stopped writing music. She simply refused to compromise her integrity in any way. Ultimately, she couldn’t cope. Just burned herself out. An obsessive need for perfection destroyed her.”

Delia Derbyshire died of renal failure at the age of 64 in 2001, when technology had finally started to catch up with her remarkable ear for music. After her death, 267 reel-to-reel tapes and a box of 1,000 papers were found in her attic. And while almost all the tapes have been digitized, none of her music has been published due to copyright issues.

Legacy

As a child hearing air raid sirens and the shoes of Lancashire factory workers on its cobblestone streets, Delia Derbyshire “saw” the potential for sound and music in everyday objects. Her trailblazing sounds are familiar to more than 100,000,000 people thanks to Doctor Who’s popularity. Today, most of her music and sound for television and radio is on tape at the BBC Sound Archives.

There have been numerous plays, documentaries and TV docudramas about Delia Derbyshire. Coventry now boasts a “Derbyshire Way.” A commemorative plaque was unveiled at her girlhood home in Coventry in 2017 as part of a BBC celebration of important musicians and venues, the ceremony performed by former Doctor Who actors Colin Baker and Nicola Bryant. That same year, Delia Derbyshire was awarded a posthumous honorary doctorate for her pioneering contributions to electronic music by Coventry University.

Today, her namesake charity, the educational Delia Derbyshire Day, gives children the opportunity to learn about and experiment with her techniques of creating music from everyday objects, encouraging the next generation to find its own creative voice.

Excelente artículo, sensible. No la conocía. Gracias!

A Genius with a Passion. Unfortunately born too early for Humanity to understand that Men and Women are created alike. Such an unfair World. Reminds me of Alan Turing. Saved the World and ended up being chemically castrated. We Humans are capable of the greatest beauty but so easily create destruction.

What a lovely article dedicated to an unsung genius….Cheers for creating this page and may her memory live on in those who continue to create inspired by her work and spirit!