In the opening decades of the 19th century, Mary Anning, a country bumpkin who lived in a town overlooking the English Channel, made some of the earliest landmark discoveries in the emerging new science of paleontology. Yet male scientists often ended up taking all the credit.

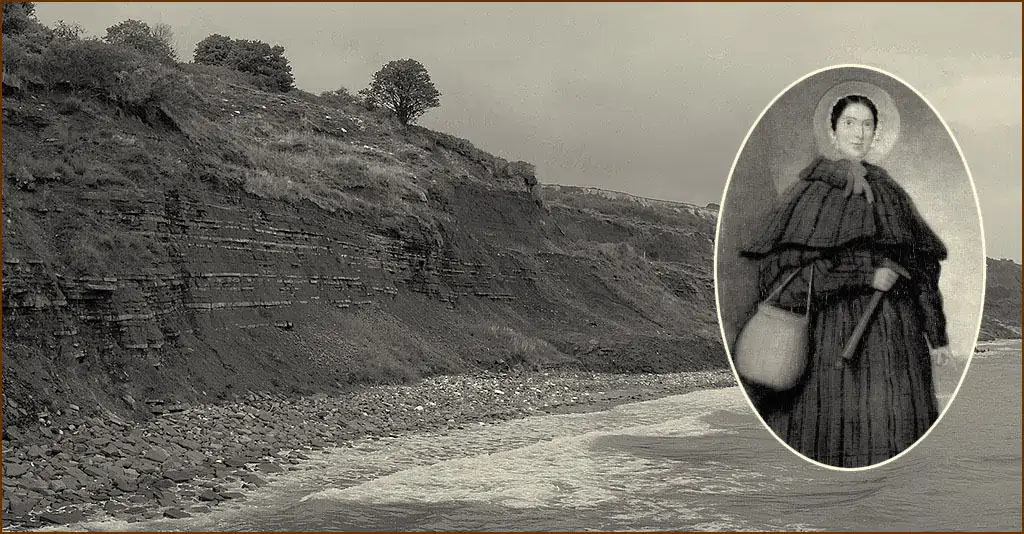

Her story begins on a stunningly beautiful stretch of coast whose eroding sandstone and chalk cliffs, periodic landslides and storm-battered beaches provide a window into the evolution of life itself. Known as the Jurassic Coast, it was there, as she scavenged for and sold the bones of long-extinct creatures to put food on her family’s table, that Mary Anning made her own bones as a trailblazing paleontologist.

Early Life

She was born in 1799 in the quiet seaside town of Lyme Regis, one of 10 children, only two of whom survived to adulthood. Her father, a cabinet maker, supplemented his income by collecting and selling fossils from the nearby beaches. A poor girl born into a working-class family of religious dissenters (Protestants who had broken with the Church of England) and already seen as “other” by her peers, she was taunted with the singsong nickname “stone girl, bone girl.” Because there was no money to send her to school, her meager education came from the local church school.

Snake Stones, Devil’s Fingers and Verteberries

While Napoleon waged war against neighboring European powers, the English were encouraged to vacation close to home. They flocked to seaside towns like Lyme Regis just as fossils and collecting were starting to become trendy. Anning’s father soon realized he could sell the curious-looking fossils he picked up on his walks along the beach to souvenir-seeking tourists.

Anning began accompanying her father when she was just five years old, helping him find, excavate and carefully clean the fossils. Some of their most popular finds were ammonites (tightly-coiled mollusk shells known as “snakestones”), belemnites (the bullet-shaped tails of creatures related to squid and cuttlefish), and “verteberries,” or fossilized vertebrae.

But her father died of tuberculosis in 1810, leaving a pregnant widow, two children and considerable debt. With the family reduced to relying on charity, Anning’s brother was apprenticed to an upholsterer while her mother continued the souvenir-sales business, encouraging Mary to pick up where her father had left off to help pay the family’s debts by selling her finds.

Not long after her father’s death, Anning, sharp-eyed and sure-footed on the rock-strewn beach, and with a knack for finding good specimens, uncovered a large ammonite that brought half a crown (roughly $50), more than her father had ever fetched for a fossil. Realizing she could earn serious money for the family, she became a regular beachcomber. After all, a major find could mean the difference between feeding the family and starving. Her first major find came when she was just 12 years old.

An Extinct “Fish-Lizard”

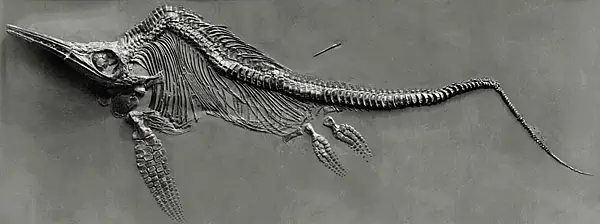

In 1811 her brother found what looked like a crocodile skull full of sharp teeth. He and a team carefully excavated the head, but Anning sensed more bones were there for the finding. The following year, she returned to the site, beginning the painstaking work of exposing the creature’s entire spinal column of 60 vertebrae, a set of ribs, and other bones. By the time she was finished, the odd creature measured an amazing 17 feet in length.

Scientists initially agreed with Anning’s brother — it had to be a crocodile. But the specimen was studied and debated for years before being named Ichthyosaurus, or “fish-lizard” — a marine reptile that lived 201-194 million years ago. And while the Annings didn’t discover the first specimen of this creature, theirs was the most complete skeleton known at the time. It created an uproar in England’s scientific and religious communities.

At a time when scientists unquestioningly accepted the biblical Genesis theory of creation, which didn’t account for extinction or evolution, this creature appeared to be older. Plus, it had long been accepted that when creatures like this disappeared, they had simply migrated to far-off lands.

Anning’s find required scientists to re-think the age of the Earth as well as the history of life upon it, and helped set the stage for Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution 48 years later with his Origin of the Species.

But all that scientific pondering didn’t put food on the family’s table. So Anning sold her complete find to a local landowner and collector for £23 (today’s equivalent of $2,240), enough to feed her small family for six months.

Mary Who??

When Anning’s find was eventually written up in an 1814 scientific journal, her name was never even mentioned. Her amazing find was, instead, credited to the landowner whose estate contained the cliff face where it was uncovered.

She would unearth several more complete Ichthyosaur skeletons over the next four years, most going to museums or making the rounds of the scientific lecture circuit. But the men — and they were always men — expounding their theories of the amazing fish-lizard never spoke of the woman who had found, extracted and cleaned the very fossils that were making them famous and building their careers. Throughout her lifetime, gender and class barriers kept Mary Anning from receiving the recognition and compensation her discoveries warranted.

Though she was becoming known in scientific circles as one of Britain’s most knowledgeable paleontologists, she was female at a time when women just didn’t “do” science. They were barred from joining the Geological Society of London. In fact, it would not be until 1904 — 57 years after Anning’s death, that the Society would admit women to its ranks.

She never published papers about her fossils; after all, no editor of a reputable scientific journal would accept a submission from a woman. Even family friend and geologist/paleontologist William Conybeare didn’t give credit where credit was due when he presented Anning’s scientific drawings to the Geological Society of London, referring to her in passing simply as the “proprietor” who sought money for the find. It was easy for the male-dominated scientific community to keep Mary Anning in her rightful place.

But she knew she deserved better. When a young admirer wrote to her, she supposedly replied, “I beg your pardon for distrusting your friendship. But the world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.” A young woman who often joined Anning on her fossil hunts was more forthright, writing, “She says the world has used her ill … These men of learning have sucked her brains and made a great deal by publishing works of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.”

A Country Bumpkin with a Scientific Mind

It was way too easy for the London scientific community to ignore Anning. After all, she was poor; she spoke with a decidedly country (Dorset) accent; and had very little formal education. Yet she was incredibly literate, devouring every fossil-related bit of news she could find in the scientific journals of her time. She even taught herself French in her twenties so she could read the works of the great French anatomist/paleontologist Georges Curvier. She was also self-taught in the fields of geology, paleontology, anatomy and the detailed art of scientific illustration.

She cleaned and prepared her specimens so professionally that when a noted scientist brought her Ichthyosaurus to public attention, he praised the preparation but credited the collector, either unable or unwilling to accept that a poor country bumpkin could have been responsible for such fine work.

Discovery of a Lifetime

In 1823, Anning made what would be the discovery of her lifetime. She found a fossilized skull — small, beady-eyed, with a mouthful of needle-shaped teeth, it resembled nothing she had ever seen. Further excavation revealed a stout torso and broad pelvis with four flippers and a tiny tail. But what set this creature apart was its long neck, accounting for almost half its nine-foot length.

Stymied, she reached out to one of the only men in Europe who might fully appreciate her find, the Reverend (and geologist/paleontologist) William Buckland, sending him her sketches of the mysterious creature. It turned out to be the skeleton of a Pliosaurus (meaning “near to reptile”), the sea’s top-ranked Jurassic-era predator, and the first articulated remains of its kind known to science.

It caused a ruckus when the legendary Cuvier suggested the fossil was a hoax because of its ridiculously long neck, stout torso and flippers. He actually accused Anning of attaching a fossilized snake’s head and vertebrae to the body of an Ichthyosaurus. Only when it became clear that the specimen had not been tampered with was the famous man forced to eat his words.

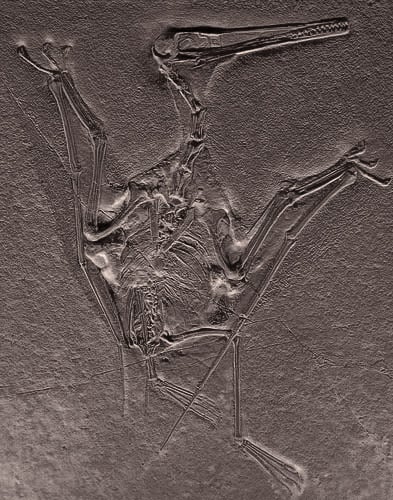

Pterodactyls and Fossilized Feces

Five years later, she unearthed an odd jumble of bones with a long tail and wings. As news of her latest find spread, scientists throughout Europe debated its identity. As it turned out, Anning had found the skeleton of the first Pterosaur (now known as a Pterodactyl) ever discovered outside Germany. With its wings and long tail, the creature was thought to be the largest-ever flying animal, with a wing span that was often thirty feet.

But not everything Anning studied was so sensational. She had long been finding lumpy, conical rocks along the shore known by locals as “bezoar stones.” Cracking some of them open, she discovered two things: (1) they were full of fish bones, and (2) they were found in the midsections of both the Ichthyosaur and Pliosaur skeletons. She again reached out to Reverend Buckland, who suggested they were, in fact, fossilized feces, later termed “coprolites.” While Buckland later got credit for it, Mary Anning had unknowingly initiated the study of fossilized poop, an important part of paleontology to this day.

On the Brink of Financial Ruin

Anning was making a name for herself as one of Britain’s most prolific fossil finders and amateur paleontologists. She even managed to save enough for a small cottage with a storefront window, where she opened Anning’s Fossil Depot. A popular spot for local tourists , she continued to sell fossils to collectors and museum curators the world over. But by 1830, major finds were harder to come by; at the same time, England’s economy was in decline, reducing the demand for the smaller fossils that were the bread and butter of her shop.

Some years earlier, a British collector had begun helping the Annings by buying up a number of specimens he later auctioned off, donating the proceeds back to them. And in 1830, Anning’s childhood friend and fellow geologist, Henry De la Beche, was inspired to paint “Duria Antiquior — A More Ancient Dorset.” He made prints of his work and sold them to raise money for the family. Complete with the Ichthyosaur, Pliosaur and Pterosaur, it was the first pictorial representation of prehistoric life actually based on the fossil record.

But eight years later, disaster struck when Anning lost her life savings of £300 (just over $400) to a bad investment. It was then the Rev. William Buckland approached the British Association for the Advancement of Science, convincing them to grant her an annuity of £25 (about $34) in honor of her many contributions to science. A seemingly paltry sum, it was, at the time, an exceedingly rare honor for a woman.

With Death Came Recognition

Anning developed breast cancer sometime around 1846. With no known treatment, she was on increasing doses of laudanum for the pain, making it impossible for her to walk long distances or poke about the nooks and crannies of seaside cliffs. When the Geological Society of London learned of her diagnosis, they raised money from its members to help with her expenses.

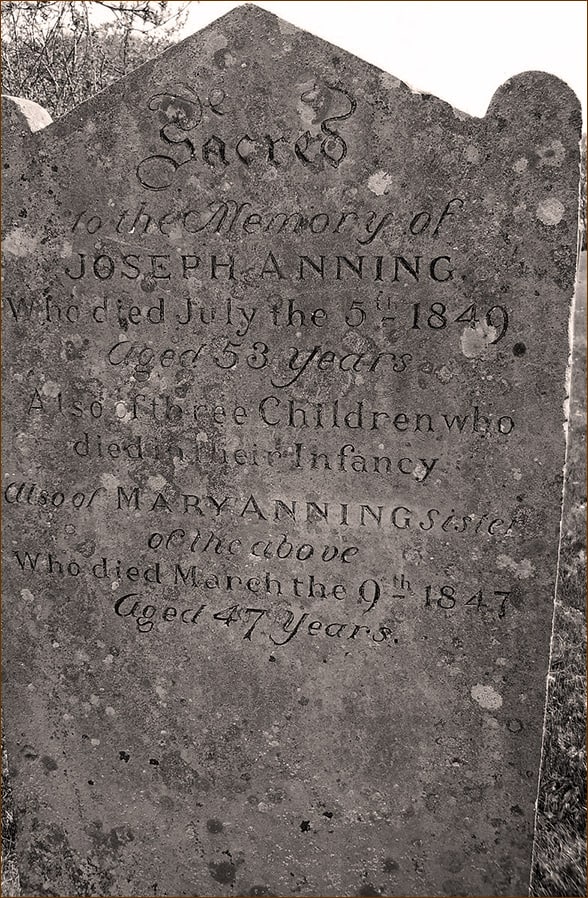

She died in 1847 at the age of 47 and was buried in the churchyard of St. Michael’s, the local parish church, alongside her brother and father, not far from the beaches where she made her greatest finds. Members of the Geological Society paid for her funeral and contributed to a stained-glass window in her memory, commemorating “her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as well as her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.” They even published her obituary in their quarterly journal, the first time they had so honored anyone — especially a woman — who was not a member.

Legacy

Because of her gender and socioeconomic status, Mary Anning wasn’t the kind of person Britain’s scientific elite cared about when George III was king and a brash young Napoleon Bonaparte was setting himself up to become Emperor of France.

But today she has emerged from history to take her rightful place as one of the world’s great early paleontologists. Britain’s Natural History Museum and the British Society for the History of Science consider her the greatest fossil hunter ever known. In fact, the Natural History Museum has made her and her finds the main attraction of their Fossil Marine Reptiles gallery.

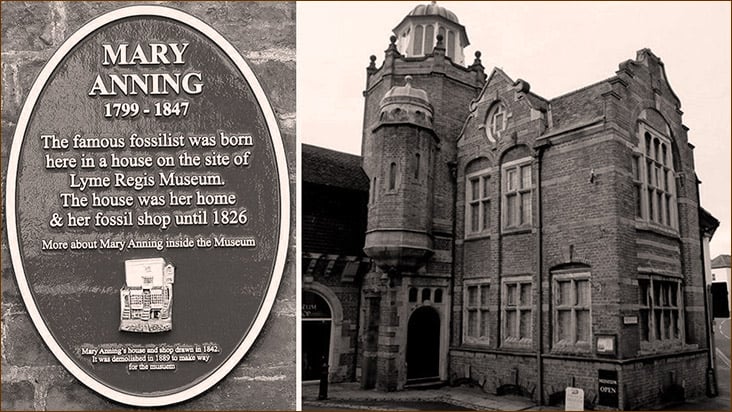

The former site of the old Anning’s Fossil Depot is now home to the Lyme Regis Museum and its Mary Anning wing, added in 2017. She has become the subject of several books and a movie. And one of her Ichthyosaurus skulls, along with her portrait, hold pride of place in the front reception hall of the Geological Society.

In 2010, the Royal Society included Anning in their list of the 10 British women who have most influenced the history of science. Swansea University in Wales launched their new research/survey vessel, the Mary Anning, in 2018. And just this year, a sculptor has been commissioned to create a public statue of Anning in her hometown of Lyme Regis.

Mary Anning’s work would prove to be nothing short of amazing. She changed the way we saw the history of the world, her discoveries proving life on Earth was far older than people thought, and that some creatures had, in fact, gone extinct. But her richest legacy may well live on in the children who still roam the Jurassic Coast beaches every summer, following in her footsteps as they hunt for fossils, proving what Mary Anning always knew — that it’s the excitement of the chase.