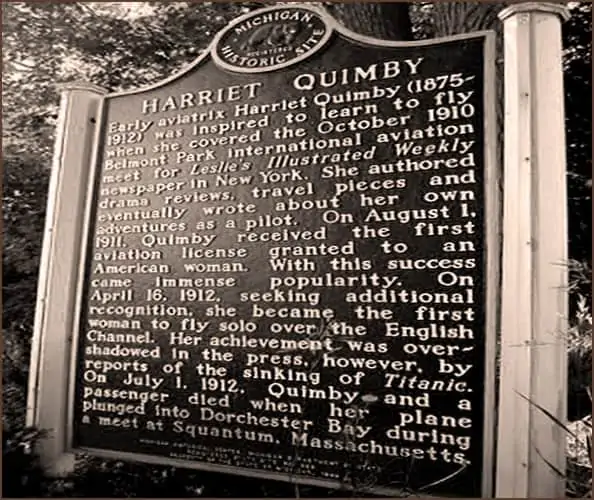

In August of 1911, 36-year-old Harriet Quimby became America’s first licensed female pilot. Dubbed “America’s First Lady of the Air,” she couldn’t know she had less than a year to revel in her title before falling from the sky to her death.

Although information about Harriet Quimby’s early life is scarce, it’s believed she was born in Michigan in 1875. Her father was a Civil War veteran whose pension application claimed he was an invalid, unable to perform manual labor for the family’s subsistence due to the “hardships of Army life.” Her mother was an herbalist who concocted and sold remedies like Quimby’s Liver Invigorator and Blood Purifier. By 1900, the family was in San Francisco where, according to the census, Harriet was an actress.

Journalist

She soon turned her attention to journalism, writing for San Francisco’s Dramatic Review, the San Francisco Call, the Chronicle, and assorted magazines before moving to New York as drama critic for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly at age 29.

After a friend married Hollywood film pioneer D. W. Griffith (known for the racist blockbuster 1915 film Birth of a Nation) and offered her a chance to try her hand at writing screenplays, seven of her 18-minute shorts shot by Griffith made it to the silent screen.

She was well on her way to becoming a successful journalist, with over 250 articles published under her byline over the course of nine years, when Leslie’s devoted an issue to aviation, assigning Quimby to cover an International Aviation Tournament at Belmont Park on Long Island in 1910. Some 150,000 spectators were there for the climax of the Wright Brothers-staged event. The assignment changed her life.

Licensed pilot

After meeting John Moisant, an aviator/flight instructor, Quimby was determined to become airborne. And by spring of 1911 she was taking flying lessons, intent on proving to herself and her readers that women could take to the skies, “going for everything in aviation that men have done: altitude, speed, endurance and the rest.” After just 33 lessons, she earned a pilot’s license from the Aero Club of America, making her America’s first licensed female pilot and only the 37th person in the world, male or female, to become licensed.

Newspapers nationwide took notice. The New York Times described her flight trial, consisting of figure eights, landing within 100 feet of a designated mark, and climbing to 160 feet. Quimby aced it. She flew five circuits of figure eights with their tight right and left turns, easily rounded a series of pylons, landed within 7′ 9″ of the mark, and ascended to 220 feet.

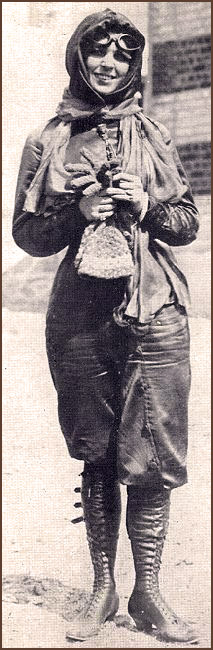

But Harriet Quimby wasn’t just a good flyer. Slim, vivacious, and described by a friend as “the prettiest girl I have ever seen,” the Times couldn’t help adding, “she wore the conventional aviator’s garb of brown shirt and trousers, close-fitting skull cap and goggles. Her face was covered with grease and dirt. But her sparkling blue eyes flashed happily as she remarked, ‘Well, I guess I get that license.'”

Celebrity aviatrix

Almost overnight, she became a celebrity aviatrix. A month later, as part of the Moisant International Aviators exhibition team, she earned $1,500 as the first woman to fly at night; two months later she earned a tidy sum as the first woman to fly over Mexico City for the inauguration of Mexico’s president-elect. It was a lucrative business, and one she encouraged other women to consider: “In my opinion, there is no reason why the aeroplane should not open a fruitful occupation for women. I see no reason why they cannot realize handsome incomes by carrying passengers between adjacent towns, why they cannot derive incomes from parcel deliveries, from taking photographs from above, or from conducting schools for flying.”

And as a seasoned journalist, she knew how to feed the public relations machine with self-written stories touting her accomplishments, always being accessible for interviews and photo ops, and creating a public persona in a custom-designed flying suit no one would forget.

Abandoning skirts

Writing in Leslie’s, “if a woman wants to fly, first of all she must abandon skirts,” Quimby did just that. She had a one-piece flying suit designed just for her. With purple being THE color at the turn of the 19th century, she chose a rich hue best described as “plum.” Described as a blouse with “knickerbockers,” it was woolen-backed satin, the woolen fabric protecting against cold air currents while the lustrous satin draped gracefully as she moved. High-topped leather boots showed off slim ankles hidden from the male gaze as she climbed into her plane. An attached hood framed her face or lay across her shoulders in a soft cowl when not in use.

It was while preparing for her Mexico City flyover Harriet Quimby got the idea to attempt a solo flight across the English Channel. At 5:30 AM on April 16, 1912, she set out in a borrowed 50-horsepower Biérot monoplane from the white cliffs of Dover, England, to Hardelot, France. The weather was bad — heavy fog, with wind predicted. The British pilot who accompanied her was so worried she might fly off course, he offered to wear her purple flying suit and make the flight for her, secretly switching places upon safely landing. Suffice to say, Harriet Quimby wasn’t having it.

The English Channel

The French coastline was 22 miles away. Circling at 1500 feet, she ascended to 6000 feet, trying to clear the fog as “the mist felt like tiny needles on my skin” and her head ached from concentrating on using the compass to stay on course. An hour into the flight, descending to find an opening in the fog, the engine flooded before “the gasoline quickly burned away and my engine began an even purr.” Finally, a great sandy beach framed by rich farmland came into view. Quimby landed on the beach after a flight of 69 minutes as curious locals rushed to the scene, immediately realizing what they had just witnessed.

Harriet Quimby succeeded in becoming the first woman to fly solo across the English Channel. But the excitement, and any celebration of her amazing achievement, were overshadowed by the news that, two days earlier, the Titanic had gone down in the icy waters of the North Atlantic with more than 1500 souls.

Back in New York, a new, pure white, 70-hp Biérot aircraft awaited her, as did a seven-day event for which the “Queen of the Channel Crossing” would earn an unheard of $100,000. It was the Boston Air Meet; and Quimby would cap off the event on its final day by becoming the first woman to fly the U.S. mail from Boston to New York. She never made that flight.

It was late afternoon on July 1, 1912, when she took the manager of the meet, William Willard, up in her new two-seater for a trial run, circling the Boston Light over Dorchester Bay. As reporters clustered around, peppering her with questions, she joked that a forced water landing wasn’t in the works. Always ready with a good quote, she said, “I’m a cat, and I don’t like the water.”

The San Francisco Examiner described what happened next: “It was sunset. The great white wings swept directly into the west and dipped toward the earth. There was a flash of the tail and, outlined before the spectators in the red glow of the west, two figures were seen to shoot from their seats into the bay, 1000 feet below, some 200 feet from shore. The powerful machine, now freed of its passengers, glided off gracefully into the wind, striking the water on an even keel before diving its nose into the mud and flipping over on its back. It was recovered undamaged save for a few broken struts and wires.”

The same could not be said for Harriet Quimby. Her death certificate cited “accidental fall from an aeroplane; multiple internal injuries and fractures; and shock” resulting in “immediate death.” And though she had jokingly tempted fate before the flight, Quimby had also left a sealed note for her parents, whom she had moved to New York, telling them that if the worst happened, she had met her fate “rejoicing.” She was 37 years old. Initially buried in New York City’s Woodlawn Cemetery, she was later reburied in a family plot in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, in Westchester County, NY.

Known today as one of American aviation’s pioneers, Harriet Quimby paved the way for every other woman flyer, Amelia Earhart and Bessie Coleman among them, with her passion for flight and her encouragement to every woman who aspired to fly. “Men flyers have given the impression that aeroplaning is very perilous work, something an ordinary mortal should not dream of attempting. But when I saw how easy men flyers handle their machines, I said I could fly. Flying is a fine, dignified sport for women, healthy and stimulating for the mind, and there is no reason to be afraid so long as one is careful.”

In 2004, Harriet Quimby’s legacy was honored with induction into the National Aviation Hall of Fame. In 1991, the US Post Office honored her with a special commemorative 50¢ air mail stamp. Converse College in Spartanburg, SC, now houses the Quimby Collection of research papers, newspaper clips, photos and documents chronicling Harriet Quimby’s life and accomplishments. And if you visit the town of Arcadia, Michigan, you’ll find a marker near the still-standing Quimby home, now an official state historical site.