“If you want something done right, do it yourself.” These were words Josephine Garis Cochrane lived by … except when it came to doing the dishes. Why had nobody invented a machine that could clean stacks of dirty dishes without chipping them? After all, it was the 19th century, when there were machines that sewed clothes and cut grass, so how hard could it be?

She would soon find out.

Born in Ohio in 1839, she was the daughter and great-granddaughter of an engineer and inventor. She came by her creative tendencies naturally despite having no formal education in science or engineering. So when faced with a problem, it was second nature for her to look for a technological solution. And if one didn’t exist, she would invent one.

Displeasing her In-laws

She was 19 and just out of high school when she married William Cochran. In an era when women had one main role in life — marrying well and taking part in their husbands’ interests and business, she made a daring move to assert her independence; while she took her husband’s last name, she added an “e” at the end (Cochrane), much to the displeasure of her in-laws.

After failing to strike it rich in the California Gold Rush, her husband moved them to Shelbyville, Illinois, where he ran a prosperous dry goods business. He installed his wife in a mansion, where she enjoyed hosting lavish dinners that showed off her irreplaceable 17th-century heirloom china. Eventually, she noticed too many pieces getting chipped from her household staff scrubbing dishes in the sink. Thinking she could do better, Cochrane tried washing her own dishes until, like every woman in America, she realized how tedious and mind-numbing it was. That’s when she decided there had to be a mechanical solution to her dilemma — something that would make the task easier not just for her, but for other women as well. Before long, she was sketching out design ideas. But she was not the first.

The first dishwasher to win a patent was invented in 1850 by Joel Houghton. A wooden box outfitted with scrubbers, it relied on a hand-cranked wheel to splash water on dirty dishes. Within 10 years, L. A. Alexander upgraded Houghton’s machine, adding a geared mechanism that allowed a user to spin dishes through a tub of still water.

Pressurized Water

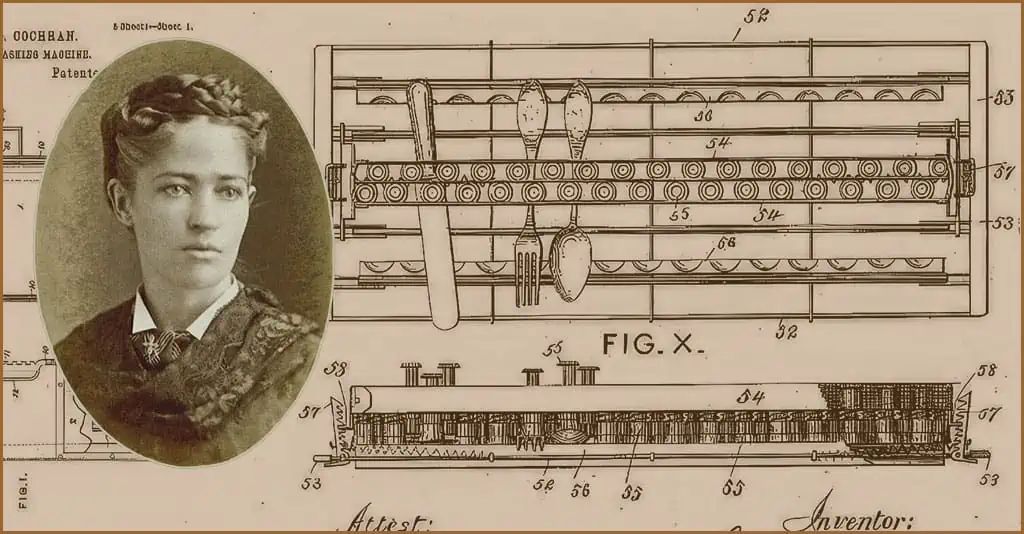

But Josephine Garis Cochrane envisioned a mechanical dishwasher that used hot water under pressure instead of scrubbers to clean dishes — and one that could hold her heirloom dishware securely in a rack of some kind while the pressure of a water sprayer cleaned and sanitized them.

Working out of a shed behind her home (a site now memorialized with a historical marker) with an eye to maximum efficiency, she measured the length, width and height of all her plates, cups and saucers; she then designed and constructed a set of wire compartments, each created to fit specific pieces. The wire compartments went inside a wheel that, in turn, sat on the bottom of a copper boiler. A container on the bottom of the machine held soap. A motor then turned the wheel, pumping hot, soapy water from the bottom of the boiler up and over the dishes.

Soon after she began work on her design, her husband died, leaving her with just $1,500 and a pile of debt. Suddenly, her idea of making a successful — and profitable — dishwashing machine became an urgent financial necessity. And while she had never been deterred by not having an engineering or technical background, she realized she needed someone to help bring her idea to fruition; and she needed someone fast. But finding good help wasn’t as easy as she thought.

Male Assistants as Impediments

As she later complained, “I couldn’t get men to do the things I wanted my way until they had tried and failed on their own. And that proved costly for me. They knew I knew nothing academically, or about mechanics, and insisted on having their own way with my invention until they convinced themselves my way was better, no matter how I had arrived at it.” Eventually she turned to a local Illinois Central Railroad mechanic named George Butters, who agreed to help her build her prototype her way. That first test machine, installed in Cochrane’s kitchen, became the envy of her friends, who began asking her to build machines for them.

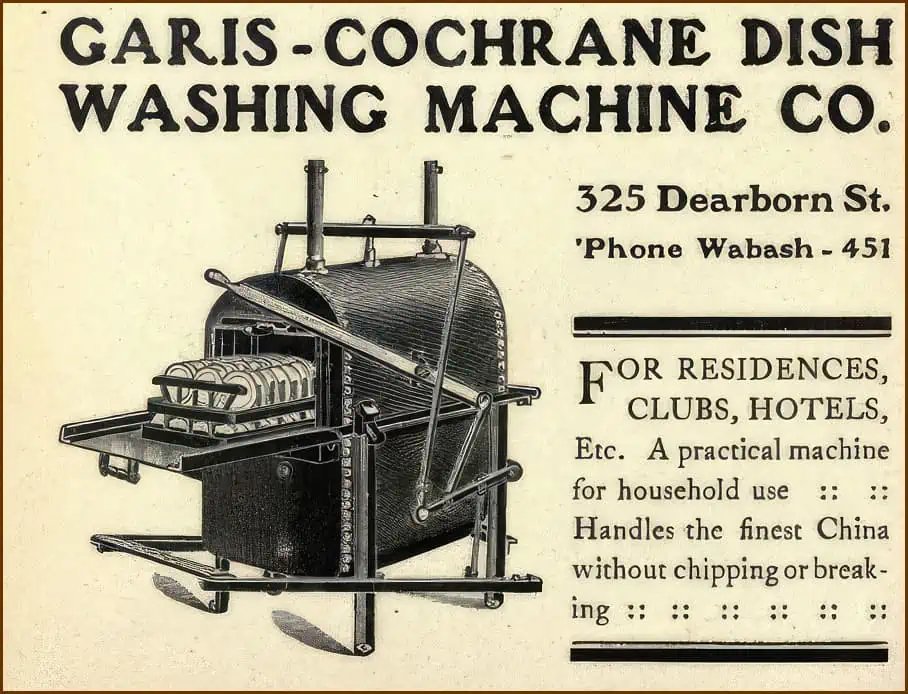

Josephine Garis Cochrane filed her first patent application in 1885; in early 1886, the U.S Patent Office issued Patent #355,139 for her “Dish Washing Machine.” With the patent secured, she founded the Garis-Cochran Dish-Washing Machine Company (named for her father and husband), supervised by George Butters in a contracted factory.

That August, the Chippewa Falls Herald ran a brief gem in its page three Tid-bits column: “Someone has invented a dishwashing machine capable of washing 3,000 dishes in half an hour. One special advantage of this machine is that it don’t lose any time talking in the back alley with policemen.”

Marketing Challenge

Initially, Cochrane hoped to sell her dishwashers directly to women at a time when household chores were assigned along gender lines. But she was also savvy enough to realize that kind of marketing campaign would run her smack up against the domestic politics of the 19th century.

In an interview with the Chicago Record-Herald in 1912, she recalled, “When it comes to buying something for the kitchen that costs $75 or $100, a woman begins at once to think of all the other things she could do with that money. She hates dishwashing — what woman does not? — but she has not learned to think of her time and comfort as being worth money. Besides, she isn’t the deciding factor when it comes to spending comparatively large sums of money for the house.” Bingo.

To her credit, she quickly pivoted from housewives to hotels and restaurants. In 1887 a wealthy friend introduced her to the manager of Chicago’s Palmer House — one of the most famous hotels in the country. He was so impressed with Cochrane’s sales pitch she left their meeting with her first commercial order.

The Ideal Clients: Hotels and Restaurants

Josephine Garis Cochrane next set her sights on Chicago’s Sherman House Hotel — but this time without an “in.” Though she was almost 50 years old, she was very much a product of her time, when a woman of her social standing didn’t leave home unless accompanied by a man. In an interview, Cochrane recalled it was “almost the hardest thing I ever did, crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone. You cannot imagine what it was like in those days for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father. And that lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t. But my reward? An $800 order.”

The Garis-Cochran Company was off and running. But Cochrane struggled to find enough up-front capital to manufacture the machines on her own. Potential investors were only interested if she resigned and turned her company’s management over to men. Clearly not having it, she soldiered on without the up-front moneymen. Which turned out to be a smart move, since many young, heavily financed companies got wiped out in the Panic of 1893. But not Cochrane’s. For her, 1893 would be a banner year — and a turning point in her life.

1893 Chicago World’s Fair

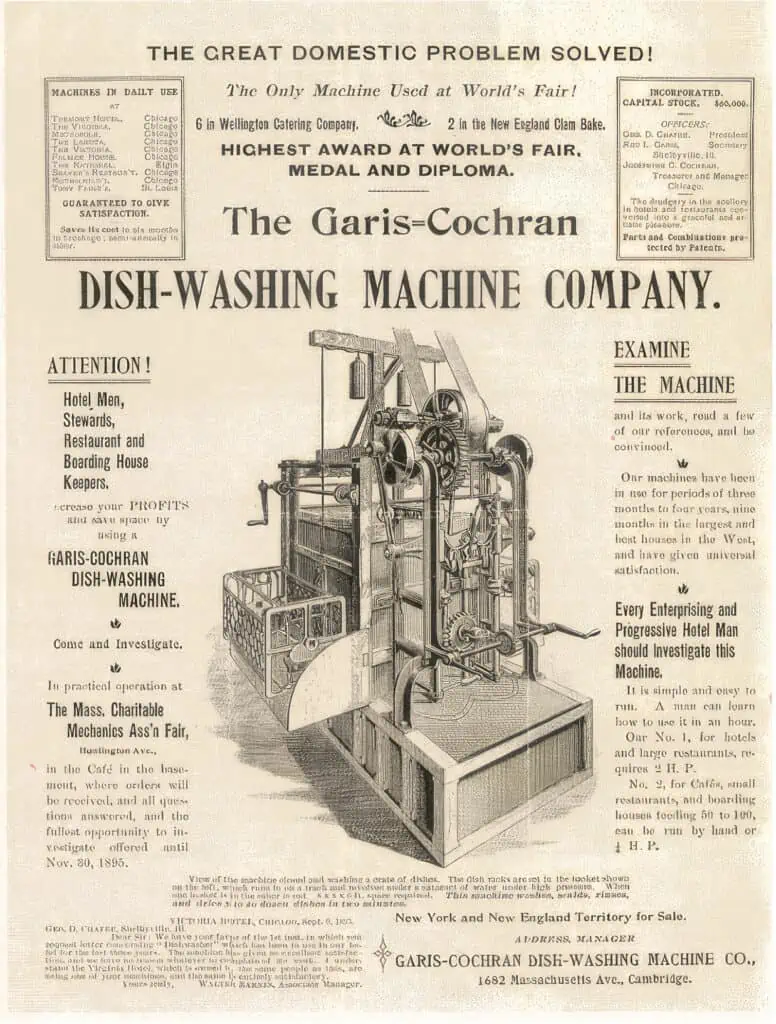

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World’s Fair (a.k.a. The World’s Columbian Exposition), a sparkling gem that stretched along Chicago’s lakefront. Over six months, more than 27 million people came to gawk and wonder at new-fangled marvels like the elevator, zippers, Cracker Jacks, the Ferris wheel, Juicy Fruit gum, and first-ever voice recording.

But one invention turning heads was an odd contraption using gears, belts and pulleys to magically “disappear” a cage full of over 200 dishes, returning them within minutes sparkling clean. It was the Garis-Cochran Dishwashing Machine — and nine others just like it were already being put to use cleaning dirty dishes in the fair’s many restaurants. Judges were so impressed they awarded it their highest prize for “best mechanical construction, durability, and adaptation to its line of work.”

In addition to giving Josephine Garis Cochrane the break she so badly needed, the exposition was a goldmine for marketing. Orders for the Garis-Cochran machines poured in from restaurants and hotels throughout Illinois and nearby states once they realized they could free up dish-duty staffs by 75% while minimizing breakage and replacement costs.

Hospitals and Colleges

And because the scalding water sanitized dishes (which was not possible with hand washing), hospitals and colleges saw her invention as a means to mitigate the spread of germs at a time when people were beginning to understand the link between germs and disease.

In 1897, Garis-Cochran Manufacturing was renamed Crescent Washing Machine Company. And Josephine Cochrane had expanded her market as far away as Alaska and Mexico. The socialite who had feared walking alone across a hotel lobby just a few years earlier now traveled far and wide to oversee installation of her invention. In 1898, she finally opened her own factory in an abandoned schoolhouse near Chicago, with George Butters as foreman and chief mechanic, overseeing three employees.

Cochrane still wanted to sell her dishwashers directly to housewives, but it was an uphill battle. Domestic models cost about $350 — too steep for most homes. Household boilers were too small to hold the amount of hot water a dishwasher required. And early ads casting dishrags and towels as some of the germiest things in the house failed. But she did find one hidden benefit — weary housewives could just store their dirty dishes in her machine, getting them out of sight and out of mind.

Death by “Nervous Exhaustion”

In 1912, Cochrane went to New York to sell her dishwashers to several new hotels and department stores, including the luxurious new Biltmore, and Lord & Taylor, which bought four Garis-Cochrans for its restaurants. She was still actively managing her company when she died at her Chicago home at the age of 74 in 1913 of paralysis due to “nervous exhaustion.” She was buried in Graceland Cemetery in Shelbyville, Illinois.

Among all the tributes that poured in after her death, just one mentioned her “untiring efforts and remarkable ability [to] have built up a large and profitable manufacturing business” at a time when the road to success was not easy for women. Josephine Cochrane never saw her invention become the sought-after, must-have household appliances they are today.

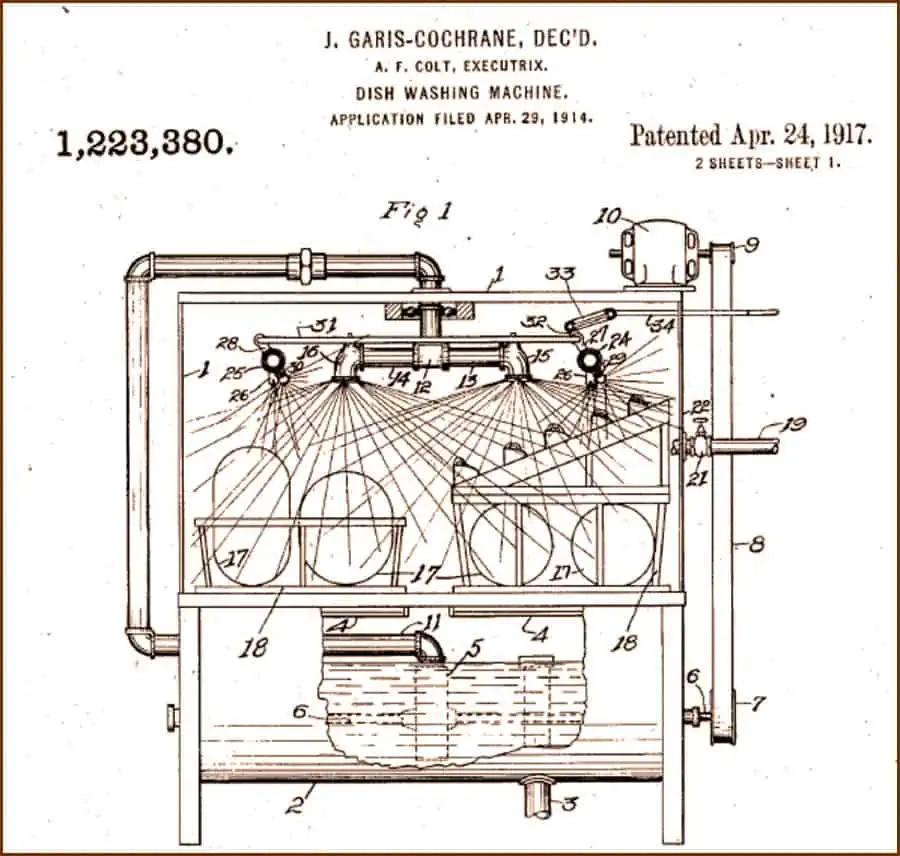

Posthumous Patent

Josephine Garis Cochrane received a second, posthumous patent in 1917 for an improved version of her dishwasher. In 1923 her Crescent Dishwashing Company trademarked its distinctive half-moon logo. Three years later, it was acquired by the Hobart Manufacturing Company, which became KitchenAid which, in 1986, was acquired by Whirlpool Corporation.

Josephine Cochrane was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006. And as a testament to the global impact of her invention, the government of Romania (where Cochrane had no connection whatsoever) issued a 2013 stamp with her likeness in honor of World Intellectual Property Day — part of a three-stamp series featuring innovative women.

It wouldn’t be until the 1950s that the combination of readily available hot water in the home, effective dishwashing detergents, and women’s change in attitudes toward housework began making dishwashers popular with the public. And while most of us take dishwashers for granted today, it wasn’t until the 1960s that Josephine Garis Cochrane’s vision was finally realized.

So, next time you load your dishes and glassware, drop in a Cascade pod, and turn on your dishwasher with the simple touch of a button or shift of a lever, take just a moment to thank Josephine Garis Cochran.