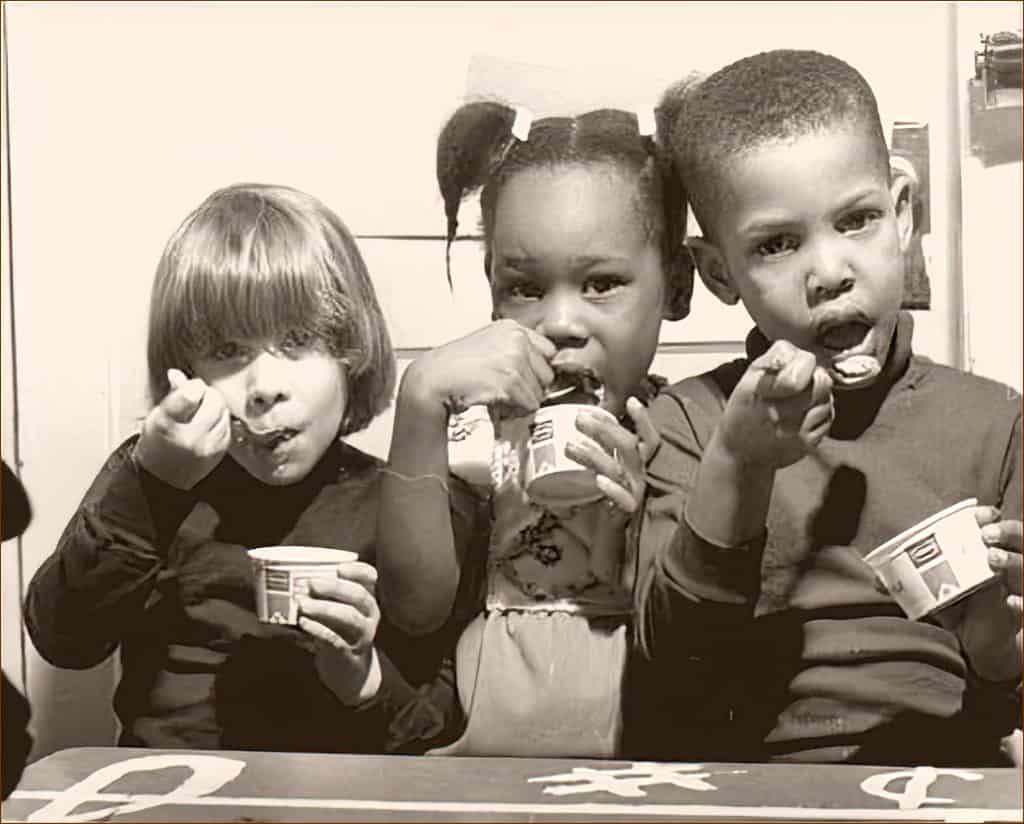

Some folks take their time with long, slow licks while others just bite right into it. We eat it from cones, in cups and with big soup spoons right out of the carton in front of our TVs. It gives us headaches and brain freeze, but we keep coming back for more. It’s ice cream. And long before anyone ever heard of two guys named Ben & Jerry; even before Philly’s own William Breyer hand-cranked his first batch of ice cream during the Civil War, these four women were making names for themselves, serving up everyone’s favorite summer treat.

Aunt Sallie Shadd:

In early 19th century Wilmington, DE, a Black woman named Betty Jackson operated a tearoom on French Street selling cakes, fruit and desserts to the elite. Her son, Jeremiah Shadd, was a well-known butcher with a fine reputation for his cured meats.

Oral local legend has it that Shadd’s wife, known by all as Aunt Sallie Shadd, was the inventor of ice cream, scooping sweet frozen desserts for the free Black community.

Shadd is said to have purchased Sallie’s freedom. Like other members of the family, she went into the catering business featuring her own signature recipes — including one using frozen cream, strawberries and sugar. According to Refrigeration: A History, Shadd’s reputation was brought to the attention of First Lady Dolley Madison, who came to Wilmington to try the frozen dessert. To her delight, she enjoyed it so much she included it on the menu for husband James Madison’s 1813 inaugural ball as something called “Strawberry Bombe Flambe.” From then on, ice cream was served at the White House.

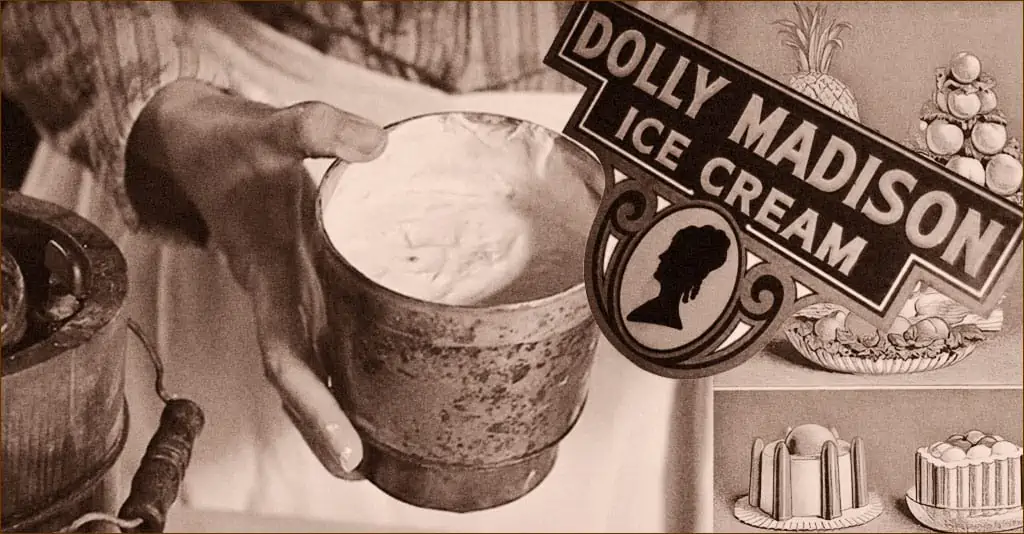

First Ice Cream in the White House

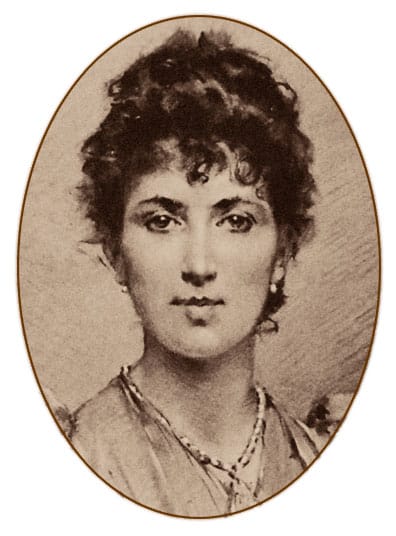

Dolley Madison received accolades for its creation. Modern-day soda fountains began advertising Dolley Madison Ice Cream, their signs bearing the former first lady’s recognizable profile. Aunt Sallie Shadd was largely forgotten. But anyone who knows their Wilmington history will tell you: it was a free Black woman who first produced that delicious White House treat.

Today, if you’re in Houston, TX, you can stop by Patra Lee’s Kitchen for a taste of Aunt Sallie’s Shortcake ice cream — strawberry ice cream mixed with bits of vanilla sponge cake, strawberry compote, and swirls of strawberry balsamic caramel sauce.

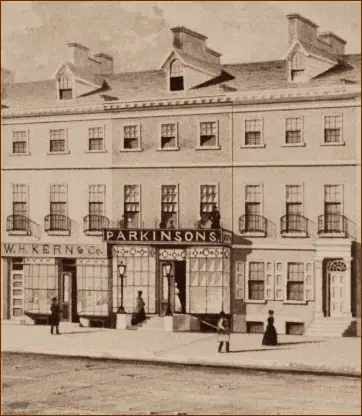

Eleanor Parkinson:

Philadelphia has a well-deserved reputation for excellence when it comes to ice cream. In 1818, Eleanor Parkinson and her husband opened adjacent stores on Chestnut Street. His was a tavern called the Pennsylvania Arms. But it was his wife’s establishment — Parkinson’s Ice Cream Saloon — that made news and made her reputation. The business took off, demand for her ice cream becoming so great her husband left his tavern to join her.

Before Parkinson opened her doors, ice cream was something of an exotic treat only available to the wealthy class. But Parkinson had a secret to her ice cream. She insisted it be made from just three readily available ingredients: cream, sugar and flavoring. While other recipes called for things like milk, eggs, gelatin, salt and a preservative, Parkinson demanded the freshest cream from local dairy farms and didn’t add preservatives. According to her, one should “use cream entirely and, on no account, mingle the slightest quantity of milk, which detracts materially from the richness and smoothness of the ices.”

“The Philadelphia Method”

Locals flocked to her Chestnut Street establishment, considering her recipes tastier and safer to eat. Before long, her simplified way of making ice cream became known as “the Philadelphia method.”

In 1844 she published The Complete Confectioner, Pastry-Cook and Baker, including over 30 recipes for ice cream, all following her by-then recognized “Philadelphia method.” Cited as a valuable approach to making ice cream, Mary J. Lincoln, author of The Boston Cookbook, touted Parkinson’s Philadelphia ice cream as “the simplest and most delicious form of ice cream.”

Nancy M. Johnson

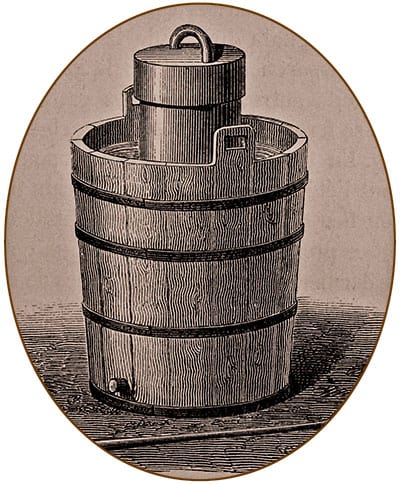

In 1843, Philadelphia resident Nancy Johnson obtained a patent for the first hand-powered ice cream freezer, described as a “hand-cranked ice cream freezer, with a movable crank and center paddle to churn the mix around.” Once out of her freezer, the icy concoctions, be they ice creams or sorbets, lasted about half an hour before melting in the days before refrigerators, when not everyone had the luxury of an icebox.

This was two years prior to passage of the Married Women’s Property Act in 1845. Prior to that, a woman had no legal identity when she married under the laws of coverture, meaning her property passed into the hands of her husband — he controlled it and, while he could not sell it without her consent, was entitled to all income and profits from said property. Women were not permitted to control their own finances, own property or sign legal agreements. Clearly, Nancy M. Johnson wasn’t having it. She was an early feminist who showed women of her time they could make their own way for themselves.

Her new device made churning the creamy mixture much easier, replacing the old “pot freezer” method in which you placed a metal pot in a bin or bucket filled with ice, added ingredients to the inner pot, then stirred like nobody’s business. An awful lot of work for an unpredictable, often lumpy dessert.

Johnson’s device featured two concentric cylinders, a lid, a paddle and a hand crank. An outer wooden pail held crushed ice; the inner tin or pewter cylinder contained the ingredients for the ice cream mix. The lid was bolted onto the bucket with the handle inserted through the top of the lid. The paddle inside attached to the handle was called a dasher. Turning the hand crank moved the paddle, scraping the frozen cream from the walls to constantly expose not-yet-frozen layers of mixed ingredients. The constant movement of the paddle produced a smoother ice cream with a consistent texture and taste.

Johnson’s invention made ice cream production faster, easier and less labor-intensive than all those hours of stirring by hand, translating into less expense and making ice cream more accessible to everyday people.

Unfortunately, Nancy Johnson couldn’t afford to manufacture her own invention, so she sold the patent to William Young for $200. But Young did the right thing, giving credit where credit was due, marketing the Johnson Patent Ice-Cream Freezer for the first time in 1848.

Agnes B. Marshall

Nineteenth-century culinary entrepreneur and celebrity chef Agnes B. Marshall was known as the Queen of Ices. But unlike our sweet treats today, some of her ice cream creations were a bit on the savory side, mixing spices, meats, custards and veggies.

Goose liver and spinach ice creams

Take, for example, her Foie Gras a la Caneton — a blend of cayenne, jelly, goose liver and eggs poured into a mold shaped like a duck. She also experimented with spinach, cucumber, pumpernickel and fish curry ice creams, leading modern-day food historian Sarah Lohman to describe Marshall’s recipes as “genius, to the point of madness.”

Her well-written, fully illustrated 1885 cookbook, The Book of Ices, contained no fewer than 177 different ice cream and dessert recipes. This was followed by her 1888 cookbook, Mrs. A. B. Marshall’s Book of Cookery, believed to include the first ice cream cone recipe. Very different from the waffle cones we know and love today, hers were oven-baked, made from almonds and flour, and known as cornets. Her books, coupled with cooking tours throughout England in front of live audiences, made her hugely successful.

She began her career in 1883 by founding Marshall’s School of Cookery. The fact that she was its main owner and driving force was unusual, considering women only earned the legal right to purchase property through England’s Married Women’s Property Act in 1884. In addition to her well-received cookbooks, she published her own magazine, The Table, featuring recipes and articles written by Marshall.

Liquid nitrogen ice cream

One of the things she wrote about in 1901 was based on contemporary scientific papers about freezing. It was the possibility of using “liquid oxygen” to freeze ice cream at home. The idea was that you could make your own ice cream by adding drops of “liquid oxygen” and “stirring with a spoon the ingredients of ice cream.” While there’s no evidence Marshall put this scientific concept to the test, an offshoot of the concept — liquid nitrogen ice cream — is one of the biggest trends in the dessert world today.

In fact, a liquid nitrogen ice cream store inspired by the 19th-century new-fangled technology opened its doors in 2014 in St. Louis. Named Ices Plain & Fancy in a nod to her book titled Fancy Ices, it offers “the finest quality ice cream, flash-churned to order using liquid nitrogen.” And when you enter the shop, you’ll see Marshall’s portrait on the wall. And for those who want to kick out the jams 19th-century style, be sure to order “Mrs. Marshall’s Old-Fashioned Ice Cream,” — a mixture of vanilla, cider, bitters and orange peels.

Dolley Madison

Oyster ice cream

Speaking of Dolley Madison, she preferred her ice cream savory — as in oyster ice cream, using small, sweet oysters from the Potomac River near her home. And while general store soda fountains bearing her name and profile eventually popped up all across America, Dolley Madison’s main contribution to ice cream history is limited to pretty much liking it publicly — in other words, in the world of ice cream, she was the equivalent of a 19th-century influencer.