For most women, being dubbed America’s “Ice Woman” would be cringe-worthy at best. But Mary Pennington, whose pioneering work in storing, shipping, refrigerating and flash-freezing perishable foods revolutionized America’s food supply, wore it as a well-deserved badge of honor.

Her life’s work was America’s “cold chain,” the system by which perishable foods travel by refrigerated trucks and rail cars to a nationwide web of chilled warehouses, cold packing plants and food factories before reaching supermarkets, restaurants and our refrigerators/freezers. A huge — and hugely important — job, considering roughly half of all the foods we consume in a year, from meat, fish, poultry, and eggs to dairy, veggies, fruit and frozen foods, depend on refrigeration for sanitation and food safety.

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1872, her family moved to Philadelphia when she was a child to be closer to her mother’s well-to-do Quaker relatives. When she wasn’t out in the garden with her father, she could be found at the library.

Chemistry

It was there, at age 12, she picked up a book on medical chemistry that would be the turning point in her life. But this was the 19th century, and girls just didn’t “do” science. So when the headmistress of her boarding school denied her request to study chemistry on the grounds it was inappropriate and most unladylike, it was no surprise.

Not one to be deterred, Mary Pennington was 18 when she approached the dean of the University of Pennsylvania to request admission to its school of science. She enrolled at Towne Scientific School (today’s School of Engineering & Applied Science, home of the oldest chemical engineering course of study in continuous existence in America and one of its first bioengineering programs), immersing herself in chemistry, biology and hygiene.

Denied her earned degree

After two years, having completed the requirements for her bachelor’s degree, sexism reared its ugly head when the Trustees, who disapproved of women at the university, refused to grant her a degree. Instead, she was given a certificate of proficiency in biology.

But no degree meant no graduate studies. That is, until faculty members intervened, using a rarely-used university statute granting grad school admission to extraordinary students. A doctoral student in Penn’s electrochemical school, Pennington earned her Ph.D. in 1895. Two years later, having devoted her studies to chemical botany, she took a one-year fellowship at Yale, focusing on physiological chemistry.

Pennington returned to Philadelphia in 1898, unable to find work as a female scientist. So she accepted a position teaching chemistry at Women’s Medical College (now Drexel University College of Medicine). It was during this period she decided to open her own business. Her first step? Securing commitments from 400 local physicians to steer at least $50/year her way. She opened the doors of the Philadelphia Clinical Laboratory in 1901.

I Scream, You Scream … Unsafe Pushcart Ice Cream

Three years later, Mary Pennington was put in charge of the bacterial lab for the Philadelphia Department of Health and Charities, where she focused on the dangers of unsafe milk, including ice cream sold from pushcarts to the city’s children. Once Pennington showed local vendors microscope slides of bacterial growth on their equipment, they began boiling their equipment to disinfect it. Industry standards she established were adopted first in Pennsylvania, and eventually nationwide.

America’s migration from rural farms to cities in the early 20th century meant food had to travel long distances, and be stored for longer periods, with no recognized industry standards for safe food handling and storage.

Food poisoning deaths

Consumers were understandably wary of refrigerated foods that often arrived damaged, spoiled or moldy. Thousands died every year from eating food that had gone bad on the way to market. Of special concern were eggs, milk, poultry, and fish.

Pennington entered the field of refrigeration in 1905 when a family friend and chief of the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry (our U.S. Food & Drug Administration) recruited her to study the effects of refrigeration on perishable foods. A year later, when the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed to secure America’s food supply, Pennington was tasked with researching and developing safe, sanitary methods of processing, storing and shipping milk, poultry, eggs and seafood.

Gender-neutral name

By 1908, she was chief of the Bureau of Chemistry’s Food Research Lab. But despite having aced her Civil Service Exam, the only way she could get the job was for her director to submit her resume under the gender-neutral name “M.E. Pennington”; after all, prominent government jobs just didn’t go to women. Throughout her tenure with the USDA, she used M. E. Pennington — and with good reason. In 1916, having been chief for 10 years, a railroad executive on whom she called told his secretary to “get rid of the woman” because he had “an appointment with Dr. Pennington, the government expert.”

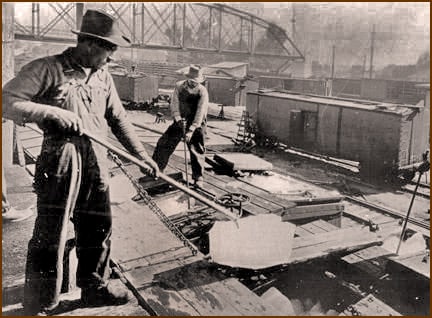

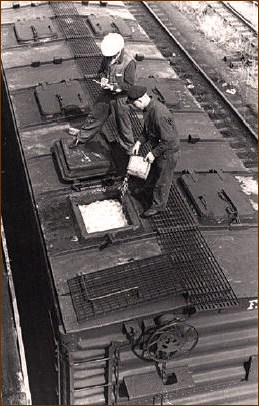

During World War I, she served on President Hoover’s War Food Administration as a consultant. With 40,000 refrigerated train cars transporting perishable food to the troops, she set out to ride the rails — 500 times, to be exact — before learning only 3,000 had the proper air circulation/refrigeration necessary for food preservation. She designed a more effectively insulated refrigerated car to safely transport food to American troops — a breakthrough that earned her a Notable Service Medal in 1919 for her contribution to the war effort.

Pennington worked as a civil servant until starting her own consulting firm in 1922, focusing on spoilage-free methods of preserving, storing and shipping perishable foods, and discovering an interest in the safety and convenience of frozen foods that dominated the later years of her professional life. In 1923 she founded the Household Refrigeration Bureau, teaching consumers the importance of refrigerators for food storage and leading the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) to name her America’s foremost authority on home refrigeration. So when The New Yorker profiled her in 1941 as the “Ice Woman,” it wasn’t much of a stretch.

The romance of ice

Mary Pennington had devoted over 40 years to educating the government and consumers about the importance of properly handling perishable food while overseeing the design and construction of modern refrigerated warehouses along with commercial and household refrigerators. She wrote numerous books on the chicken and the egg, including a 1915 USDA Bulletin on How to Kill and Bleed Market Poultry, and her two-volume set, Eggs Book I: Whence Come Our Eggs and Poultry? and Eggs Book II: The Best of Eggs and Poultry, distributed at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. She also penned 13 pamphlets to educate the public about household refrigeration, with catchy titles like Journeys with Refrigerated Foods and The Romance of Ice.

Over a long career, she accumulated her share of accolades and awards. In 1940, she was the American Chemical Society’s recipient of the Francis P. Garvan Gold Medal honoring outstanding achievement in science by a woman. Seven years later, she was elected a Fellow by the American Society of Refrigerating Engineers. She was the first woman elected to the Poultry Historical Society Hall of Fame in 1959 thanks to her invention of a new type of egg-packing case that reduced breakage. And she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2018.

Mary Engle Pennington never retired. She was still active as a consultant and Vice President of the American Institute of Refrigeration when she died of a heart attack in Manhattan at the age of 80 in 1952. She is buried in her hometown of Philadelphia in Laurel Hill Cemetery.

And when it came to her own kitchen, it was completely electric — uncommon for the time. But until the day she died, Mary Engle Pennington proudly ate frozen, refrigerated and canned foods from every part of the United States every day, knowing she had helped make them safe for consumption.