It’s 1907. Imagine you’re an Irish immigrant cooking for a wealthy family when a man you’ve never seen before shows up, accusing you of spreading death and disease, and asking for samples of your blood, urine, and stool. Mary Mallon did what any woman confronted by a strange man making such an outrageous, indecent-sounding demand would do. She grabbed a nearby carving knife and lunged at him. Luckily, the man, George Soper, escaped unscathed. But for Mary Mallon, who became known as “Typhoid Mary,” it was the start of a nightmare that lasted the rest of her life.

Less than a mile from bustling Manhattan, North Brother Island is located on the East River between the Bronx and Riker’s Island. It has a long and fabled history. In 1904 it was the site of the wreck of the steamship General Slocum in which 1,021 people died. It was later used to quarantine and treat tuberculosis patients. It housed returning veterans of World War II who faced a housing shortage.

Today it’s home to several species of shore birds. Crumbling red brick buildings, shattered windows, and thick vines snaking in and out of rusty framework are all that’s left of what was once Riverside Hospital, whose most famous patient was Mary Mallon, the subject of one of America’s first epidemiological investigations of an infectious disease.

Poor Irish Immigrant

Born in a poor Irish village in 1869, she traveled alone to America at the age of 15, staying with an aunt and uncle. Like many single young Irish women, she found work as a domestic servant and was soon recognized for her cooking skills. Before long, Mallon settled into a well-paying career as a cook, working for some of New York City’s most affluent families.

Hired in the summer of 1906 by wealthy banker Charles H. Warren, whose family and servants vacationed in Oyster Bay, Long Island, she arrived in early August. Three weeks later, six of the 11 inhabitants of the Warren household showed symptoms of typhoid fever. The Warrens were horrified. After all, wasn’t typhoid fever a disease of poverty, thriving in the overcrowded, filthy conditions of New York slums like the notorious Five Points and Hell’s Kitchen, a world away from genteel Oyster Bay?

Today we understand typhoid fever as a major cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries. In 2019, estimates cited about 9 million cases and 110,000 associated deaths a year from the extremely contagious bacteria Salmonella typhi which lives in the intestines and bloodstream. From there it travels to the lymph nodes, gallbladder, liver, and spleen, spreading through contaminated food and water. And chronic carriers, many of whom never show symptoms, can shed bacteria for long periods of time in their communities, silently spreading the disease.

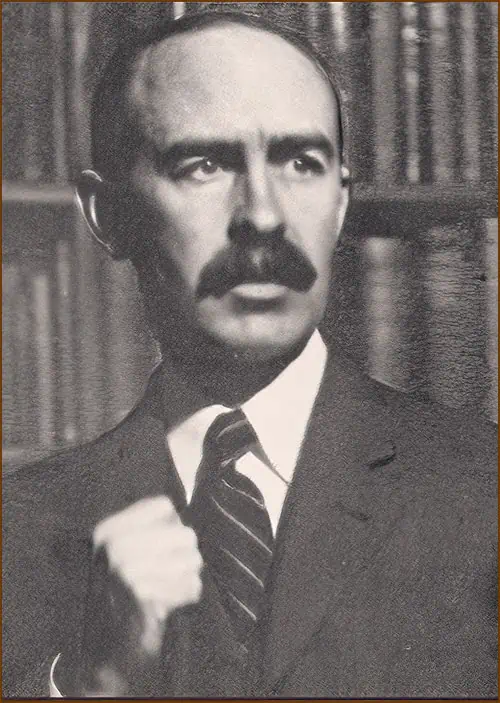

But in the fall of 1906, all Charles Warren’s landlord knew was that the disease outbreak could ruin his ability to rent out his summer home again. So, in a “who ya gonna call” moment, he reached out to George Soper, Ph.D. Not a medical doctor but a civil engineer (or, as one paper described him, “a doctor to sick cities”), Soper was an expert in sanitation, his work investigating other disease outbreaks for New York State earning him the title “epidemic fighter.” And he believed typhoid could be quickly spread by just one asymptomatic person serving as a carrier.

The Culprit: Mary Mallon

He tested everyone and everything, from the source of the home’s drinking water and its plumbing system to an old woman who lived on the beach and sold clams to the locals when he thought shellfish might be the culprit. He questioned those who were ill, including the cook — who reported nothing more than a slight case of the flu. But when all his analyses came back negative, Soper was convinced: it had to be Mary Mallon.

Tracing all the occupants and visitors to the home on or before August 20, since the incubation period for typhoid was about 10-14 days, one thing stood out — on August 4, the Warren family had engaged a new cook. Now, in the middle of his investigations, that cook had suddenly left without giving notice or explanation some three weeks after the typhoid outbreak.

Armed with a description of Mallon — a tall, buxom woman about 40, with blue eyes and a firm mouth and jaw who people remembered as “a pretty good cook,” but “not particularly clean in her work habits” — Soper visited employment agencies throughout the city, tracing Mallon’s work history over 10 years. What he learned was that every single home where she had worked during that period had an outbreak of typhoid fever. And after each outbreak, Mallon quickly but quietly left, finding employment elsewhere under a series of different names.

While Soper believed he now knew the “who” of the mystery, he struggled with the “how” when it came to the spread of typhoid germs. After all, the high temperatures required to cook food would have killed the bacteria. The answer lay in one of Mallon’s most popular desserts –vanilla ice cream topped with fresh-cut peaches. Comparing her preparation of the cold dessert with her hot, cooked meals, he realized handling and cutting up the peaches provided the perfect way for a cook to “cleanse her hands of microbes and pass them on.” Sure enough, when questioned, Mallon freely admitted she never washed her hand, even after using the bathroom. Today there’s no defending her appalling personal hygiene habits; but remember — these were early days for understanding “germ theory” and the role bacteria played in the field of infectious disease.

Chasing Typhoid Mary

Finally knowing how Mallon was transmitting disease, Soper set out to track her down. In March 1907, he found her working in a Park Avenue brownstone. Confronting her with his evidence, Soper presented what must have seemed to her an outrageous request for samples of her blood, urine, and stool. To say she was less than compliant is an understatement … she grabbed a carving fork and advanced toward him.

Never one to give up, he convinced Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, an early advocate of hygiene and public health, to work with him. She later wrote, “It was Mary’s tragedy that she could not trust us.” After successfully evading authorities for hours, Mallon was found when pursuers spotted a small piece of her dress sticking out from under the door of her hiding place. It took the efforts of Soper, Dr. Baker, and four police officers to bring her to a nearby hospital where she tested positive for Salmonella typhi. Follow-up tests confirmed the diagnosis.

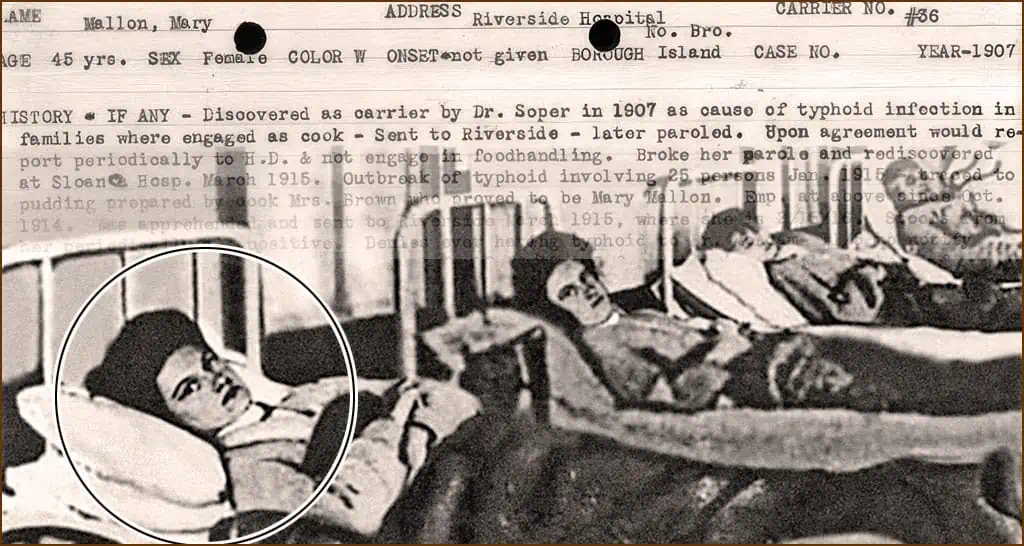

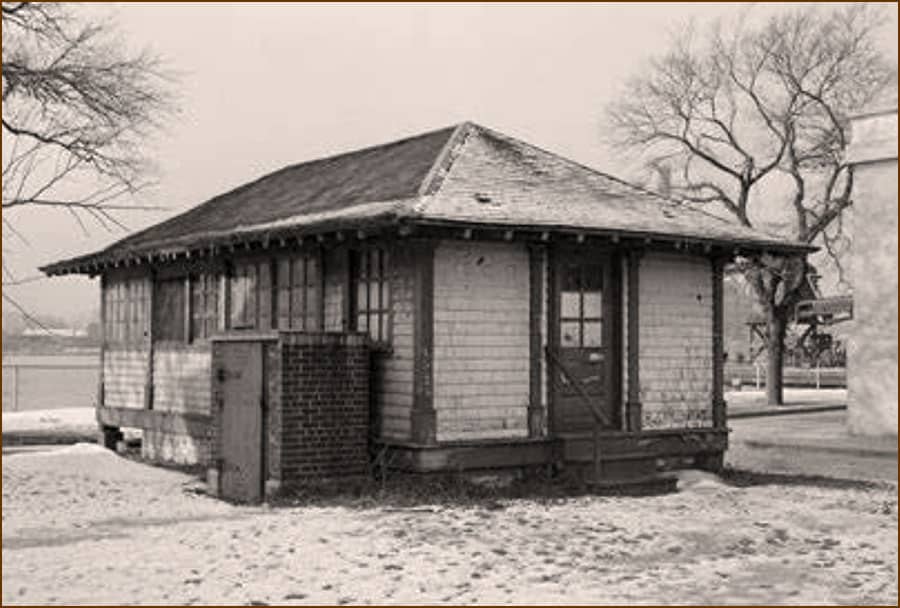

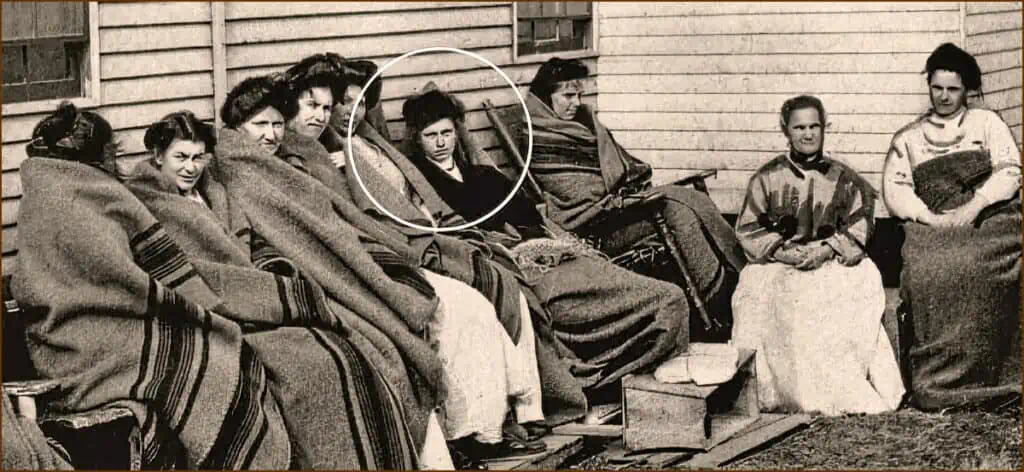

On March 19, 1907, Typhoid Mary was transferred by the Department of Health to North Brother Island, where she was quarantined in a small hut separate from the main building. In two years of confinement, 120 out of 163 of her stool samples tested positive for Salmonella, yet she never demonstrated any symptoms (fever, headache, abdominal pain, constipation and/or diarrhea) and stubbornly, vehemently denied she could be a spreader.

Finding “Patient Zero”

As for George Soper, he became the first to describe a “healthy carrier” of Salmonella typhi in the United States. Not only did his work show how one symptom-free carrier could be “patient zero” at the root of a disease outbreak; it sparked a vigorous debate about personal freedom vs. the greater good of the public health. He eventually published the results of his investigation in the June 15th, 1907, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

It’s a good bet Mary Mallon never understood what it meant to be an asymptomatic spreader because no one had ever fully explained it to her in a way she could understand. Instead, doctors treated her with Urotropine (a urinary tract antiseptic) to kill the S. typhi germs excreted in her urine; brewer’s yeast (to improve her intestinal flora); Anti-Auto-Tox (for liver function and constipation) and given regular laxative purges. And she was offered a cure — the surgical removal of her gallbladder. Despite being assured by the gynecologist who treated the hospital’s female patients that he would have “the best surgeon in town do the cutting,” she flatly refused.

In 1909, the flagship newspaper of William Randolph Hearst’s publishing empire, New York American, dubbed her “Typhoid Mary,” vilifying her as “the most harmless and yet the most dangerous woman in America” and a “human vehicle” under constant guard so she didn’t escape.

Mallon Court Suit Thrown Out

That same year, when Mallon sued the health department, claiming “this contention that I am a perpetual menace in the spread of typhoid germs is not true. I am treated like an outcast, a criminal,” her case was promptly denied by the New York Supreme Court. Finally, in February 1910, with a new city health commissioner in place, Mallon was released on one condition: she must never work as a cook again.

After her release, she worked for a time as a laundress — a job she found not only menial and unsatisfying but one that paid poorly and offered none of the perks that came from working for the city’s elite. Plus, all she knew was cooking. Still stubbornly unconvinced she was not a danger to society and working under a series of aliases to evade the New York City Health Department, she went back to cooking in hotels, spas and institutions in New York and New Jersey. But when a 1915 typhoid outbreak sickened 25 people at Sloane Maternity Hospital, George Soper was called in again. The hospital cook working under the name “Mrs. Brown” was none other than Typhoid Mary.

Media Hysteria

The press had a field day with the news, and public sentiment turned against “Typhoid Mary.” In March 1915, Mallon was apprehended for the second and final time and sent back to North Brother Island, where she spent the rest of her life in quarantine. A month later, Washington’s Tacoma Times carried a mocking front-page story depicting her as a “Witch in New York!”, writing “but this 20th-century witch does not weave incantations and scatter curses over the community. No! She scatters GERMS — typhoid germs!”

On Christmas morning in 1932, a delivery man found Mary Mallon on the floor of her cottage, paralyzed. She had suffered a stroke and would never walk again. For the next six years she was cared for in Riverside Hospital.

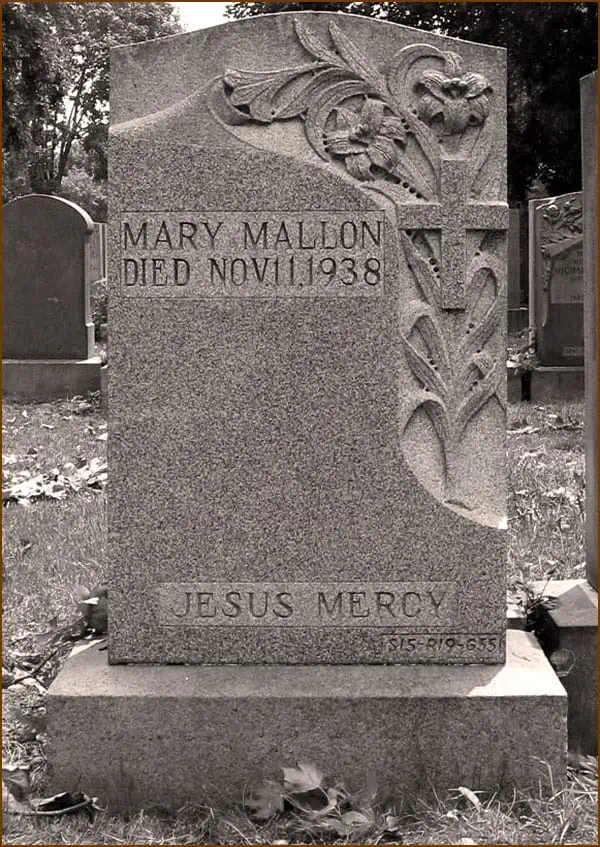

Having spent 26 years in quarantine on North Brother Island, Mallon died in November 1938 at the age of 69. Her death certificate cited the cause of death as “terminal bronchopneumonia” with “typhoid carrier” listed as a contributing factor. Her body was hurriedly removed and cremated, her ashes buried at Old St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. Nine people attended her funeral at St. Luke’s Church but refused to identify themselves to newspapers. While an autopsy supposedly revealed she had shed Salmonella typhi bacteria from gallstones, raising the question of what might have been had she undergone surgery, some researchers insist there was no autopsy — that this was just another urban legend floated to calm ongoing bioethical arguments.

Although researchers agree early data is unreliable and many cases went unreported, it’s believed at least 47 people were infected with Salmonella typhi by Typhoid Mary, three of whom died. By the time of her death in 1938, authorities had also changed their response to public health threats. More than 400 healthy carriers of typhoid had been identified by New York officials, none of whom were forced into confinement and long-term quarantine.

A Time Before Antibiotics

In these days of COVID, you could argue Mary Mallon’s story has a place in the ongoing debate over the legalities and moral issues involved in depriving people of their freedoms in the name of the greater good and public health. But her case belonged to another time — a time before antibiotics; a time when the theory of germs and disease-causing bacteria was only just emerging; and a time when neither Mallon nor the public really understood what she was being accused of. Today doctors have two vaccines to prevent typhoid fever. It can also be treated with antibiotics. And Salmonella typhi bacteria can still be shed by chronic asymptomatic carriers for decades. Mary Mallon, a.k.a. “Typhoid Mary,” was the first and most famous of those.

But she hasn’t been forgotten. The October/November 2004 issue of Irish America Magazine reported that medical students of infectious disease at nearby Montefiore Hospital make regular pilgrimages to her grave, its stone inscribed with her name, dates, and two simple words: “Jesus Mercy.”