If anything, the hardest job for Spotted Wolf was just getting into the Marine Corps. She started thinking about enlisting at 18, right after America entered World War II, but was met with resistance every step of the way, with one recruitment officer telling her war was “really not for women.” Nevertheless, she persisted and, at age 20, was accepted into the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in the summer of 1943.

WWI ‘Marinettes’

Women were first allowed to join the Marines to perform clerical duties in 1918. Known as “Marinettes,” they assume stateside roles to free their battle-ready male counterparts to go to France. A year later, they were phased out of the Marine Corps, their contributions recognized with induction into the American Legion.

Between World Wars, much thought but very little serious discussion was devoted to whether women should be allowed to enlist directly into the armed services or be kept separate, in auxiliaries, serving as cooks, waitresses, canteen workers, hostesses, librarians, chauffeurs, messengers … or even strolling minstrels.

Marine Corps Women’s Reserve

In late 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed off on the formation of a Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, making the Marines the last branch of service to accept women into its ranks. But all the hoo-ha over female Marines didn’t end there. After all, what would these women be called?

By now, the public was used to cute, catchy nicknames for its military women — Navy WAVES, Army WACS and Coast Guard SPARS — and was quick to weigh in. Suggestions included Femarines; Dainty Devil-Dogs; Women’s Leather-neck Aides; Glamarines and even Sub-Marines until General Thomas Holcomb put an end to the silliness by declaring, “They are Marines. They don’t have a nickname and they don’t need one. They train in a Marine atmosphere at a Marine post. They inherit the traditions of Marines. They are Marines.”

The first official call for women to enlist in the U.S.M.C. Women’s Reserve went out in February of 1943 with posters encouraging women to “Be a Marine … Free a Man to Fight!”

First of 19,000 in World War II

But the bar was high. You had to be a U.S. citizen; not be married to a Marine; have no children under 18; stand at least 60″ and weigh at least 95 pounds; have good vision and sound teeth; and be 20-35 years old with at least two years of high school. Enlisted women initially trained at the Naval Training School at Hunter College in the Bronx, New York, until the Corps got its own training center at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where almost 19,000 women became Marines during World War II.

In boot camp, Minnie Spotted Wolf attended half-day sessions to observe hand-to-hand combat, the use of mortars, bazookas, flame-throwers, guns, amphibious assault vehicles and landing craft. Her days began with 0545 reveille, followed by close order drills, a rigorous exercise program and a diet designed to build up the new recruits.

Heavy equipment

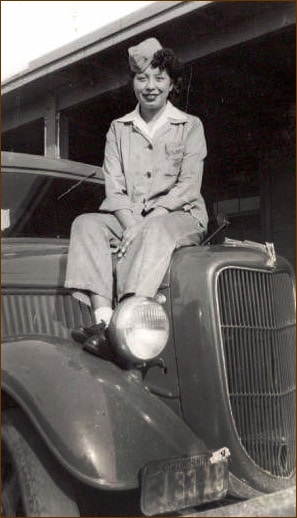

From there, she served in California and Hawaii. Described by Overdrive Magazine as “slender, tough and determined,” she drove heavy equipment trucks like the International M-5H-6 and Chevrolet WA — a job usually done by men. As further testimony to her considerable abilities behind the wheel, she was assigned as a driver for generals and high-ranking officers visiting the bases.

During her four years of service, the press found Spotted Wolf irresistible, with no fewer than 81 articles appearing in newspapers from coast to coast in August of 1943. The Austin American’s headline read, “Marines Grab Indian Queen” while Salt Lake City’s Deseret News announced “Rootin’ Tootin’ Lassie Signs Up,” on one hand touting her abilities as a “bronc-busting, bridge-building, truck-driving Indian Queen” while, on the other, describing her as “a slender and modest little morsel.”

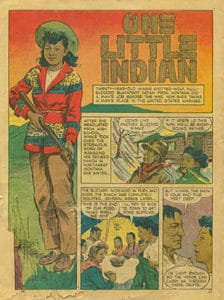

Star of a comic book

A four-page comic book about her was even published to promote the war effort. Titled “One Little Indian,” it appeared in Calling All Girls magazine for teens, with dramatic tales of how “20-year-old Minnie Spotted Wolf, full-blooded Blackfeet Indian, did a man’s job before the war. Now she’s taking a man’s place in the U.S. Marines.”

She served honorably from 1943 to 1947, after which she returned to Montana, married a farmer named Robert England, and raised four children.

She earned a two-year degree in 1955, followed by a Bachelor’s Degree in elementary education from the College of Great Falls in 1969, teaching at reservation schools and little country schools throughout Montana for 29 years. But she was no prim stereotypical schoolmarm; her daughter recalled “she usually kept a horse for riding near where she worked,” and “could outride guys into her early 50s.”

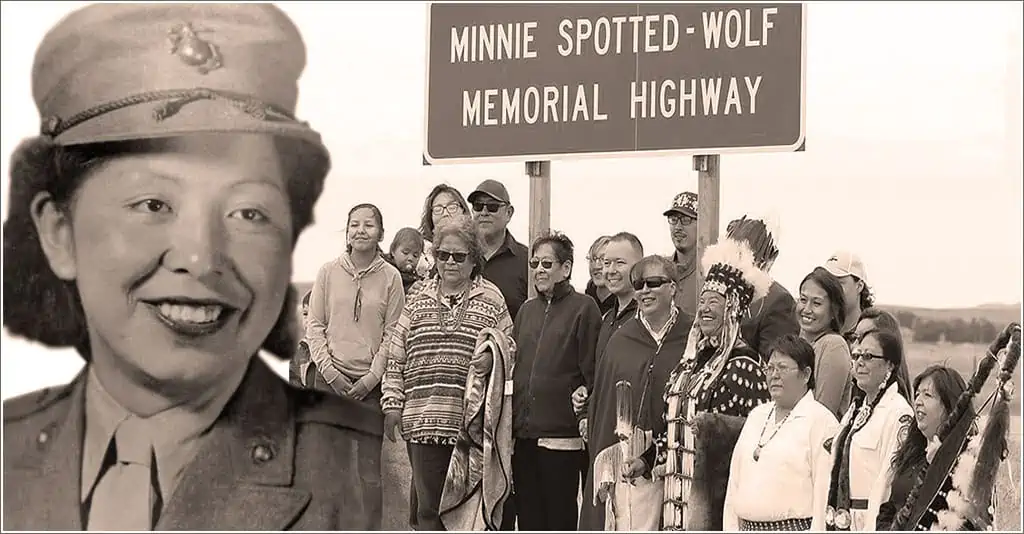

Minnie Spotted Wolf died on January 1, 1988, leaving a legacy of service as a U.S. Marine and beloved teacher. On a chilly Friday in August, dignitaries arrived as her family and members of the Blackfeet tribe gathered near mile marker 85 on U.S. Highway 89 in Pondera County, Montana. One lane of traffic near a metal monument at the southern entry into Blackfeet Country was blocked by the D.O.T. as seats in front of a podium began to fill. While Montana’s highways had long been named for men, that was about to change.

Dedicated on August 9, 2019, 76 years after her enlistment, a stretch of U.S. Highway 89 is now officially known as Minnie Spotted Wolf Memorial Highway. Her daughter spoke of her mother’s pride in her heritage and her military career, saying, “She wasn’t in the military just for herself, but for the Indian people. She wanted others to know where she came from and who she was.”

Minnie Spotted Wolf was always a patriot, active in her local American Legion Post #127 and proudly wearing her Post uniform as flag bearer during the annual Indian Days celebration and whenever she attended military funerals. When she was laid to rest following her death on January 1, 1988, at the age of 65, she was buried in that uniform, with black slacks and coat.

Shame on American school system for glossing over brave women like Minnie in their teaching. I am 70 years old

with a Masters in Education/Spec Ed( retired)never heard her name or celebrating Native American day-yet we know all the gossip of Harry and his woes! Come on America, give women their dues!!!Rosemary Gebhart BA Psychology ,MA in Early Education AND Special Education-makes me angry!!!

Thank you Minnie Spotted Wolf for paving the way for the future generations of female Warriors to come after you. My Service thanks you. That is a legacy that you helped form. I stand at attention and render a salute to you, Ma’am! Semper Fi

Minnie is or was someone I would have been able to call a true patriot. Rest in peace from a Vietnam combat veteran of Oklahoma. Well written article