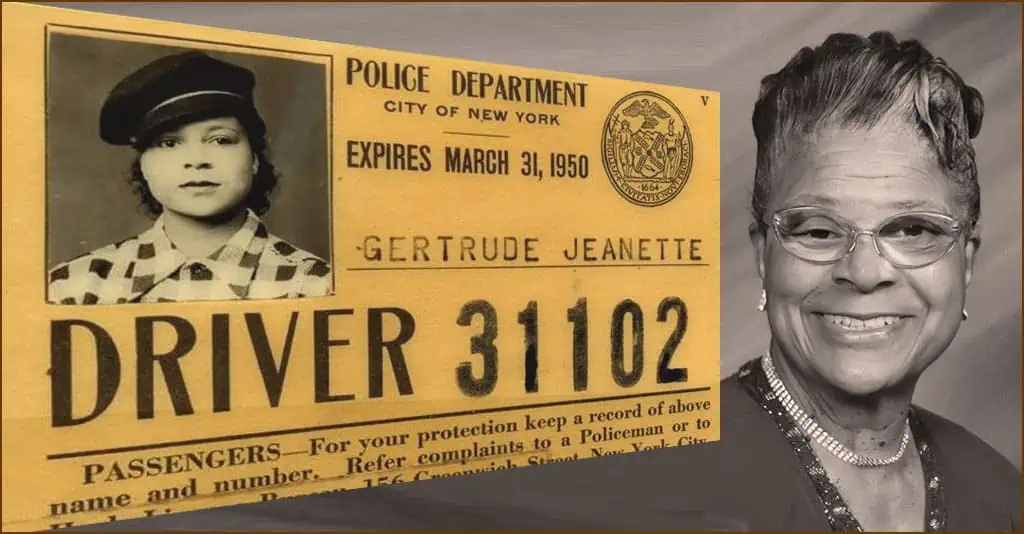

Gertrude Jeannette was a true trailblazer as the first woman to get a motorcycle license in Manhattan and The Big Apple’s first licensed female cabdriver. Perhaps her more important accomplishments were as an actor, director and playwright who mentored a generation of Black actors in New York. But none of that would have happened were it not for a persistent childhood stutter and a man named Joe Jeannette who loved to dance.

Born in a suburb of Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1914, Jeannette attended segregated Dunbar High School, where every day started with the anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” After graduation, she planned to attend Fisk University in Tennessee. But life took a turn the night of her senior prom when she met the man who would become her husband.

Lindy Hop and Marriage Proposal

Joe Jeannette, also born in Arkansas, was visiting from New York when he showed up at the dance. Later in life, his widow recalled, “He could dance — I never could keep up with him.” The couple danced the Lindy Hop, born in Harlem and made popular during the swing era of the 1930s and ’40s. By the time the dance ended, Joe Jeannette had proposed.

But Gertrude Hadley had a mind of her own and replied, “Just because I’m a small-town girl, I’m not a fool,” before walking off the dance floor. Nevertheless, Joe Jeannette persisted; the couple eloped in 1933, arriving in New York City’s Harlem in 1934.

It was there, beneath the elevated train tracks on today’s Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Harlem, Jeannette learned to ride a motorcycle. Her husband, who was president of the Harlem Dusters club, some 50 riders strong, would push her in and out between the pillars of the “el” with the engine off, just so she could get the feel of the bike. By 1935, she drove well enough to qualify as the first woman in Manhattan to get a motorcycle license.

American Negro Theatre

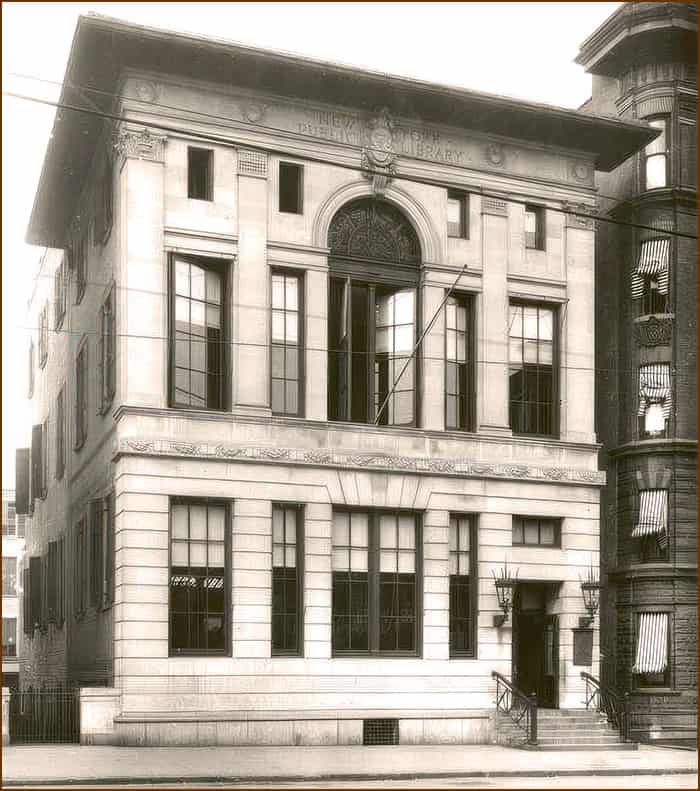

By the early 1940s, having put her education on hold, Gertrude Jeannette had enrolled in a WPA-sponsored bookkeeping class. It was there she met one of the founders of the American Negro Theatre, who noticed she had a stammer and suggested she take advantage of their speech therapy classes. The only catch? Acting classes were part of the speech therapy curriculum. Becoming an actor was the farthest thing from Gertrude Jeannette’s mind. But to pay for the speech therapist, Jeannette realized she needed a job.

Without telling her husband, she answered a 1942 ad for women to replace the city’s male cabbies drafted into World War II. Having learned to drive in Arkansas, she knew she could handle a taxi. Thirty-two women took the required driving test; only two passed, and one had citations on her driving record. The only woman left standing was Gertrude Jeannette who, according to Allan Fromberg, New York City’s deputy commissioner for public affairs, became the first licensed female cabdriver in Manhattan.

Manhattan Taxi Driver

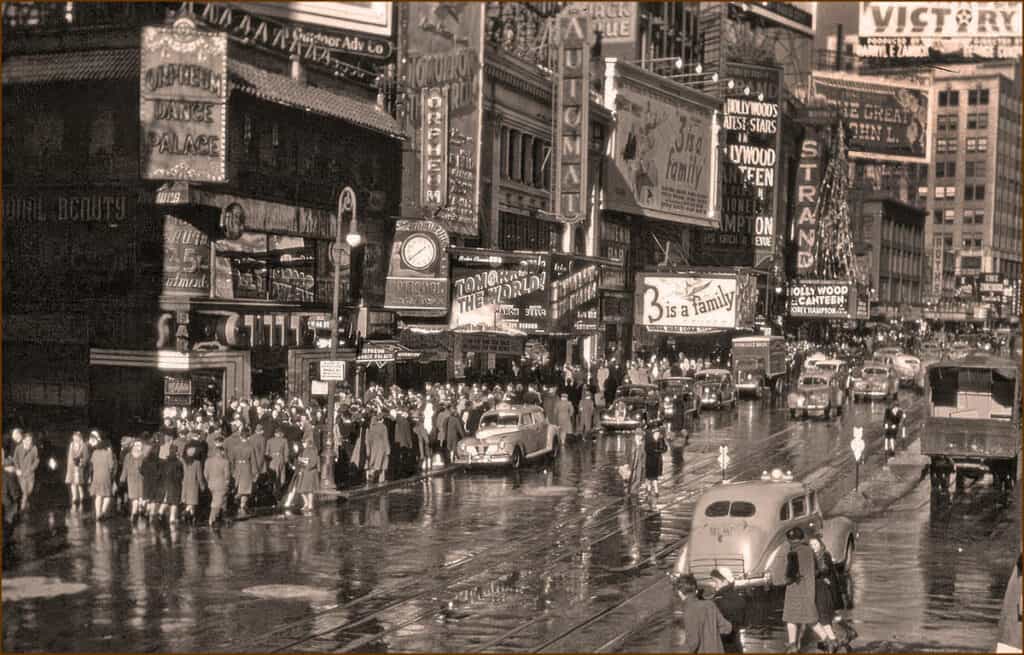

Though she had yet to start acting classes, her first day on the job had its share of drama. She rolled up in front of the Waldorf-Astoria and was cut off by other cabbies. “In those days, they didn’t allow Black drivers to work downtown,” recalled Jeannette. Not to be deterred, she calmly kept her place on the taxi line until a Checker cab suddenly veered in front of her. “I rammed my fender under his, swung it over to the right and ripped it,” she remembered in 2011 at a ceremony honoring her at Harlem’s Dwyer Cultural Center. Naturally, the other driver had a few choice words for her to which she countered, “You tried to cut in front of me! I couldn’t stop.” Shocked to hear her voice, the angry driver yelled, “A woman driver! A woman driver!” Jeannette was later scolded by an inspector … but not before she drove off with her very first fare.

As planned, she used her taxi earnings for speech therapy and the requisite acting classes. She already knew she had an excellent memory — after all, she had to learn the map of New York City to get her cab license. So she only had to read a script once or twice to memorize lines. And she discovered that if she was confident delivering her lines, she didn’t stammer.

The Theatre also required its students to audition for roles, which Jeannette did, albeit reluctantly. And every time she auditioned, she got the part. Which is how she found herself running lines with up-and-coming actors like Sidney Poitier (who paid for his lessons by working as a janitor), Ruby Dee and husband Ossie Davis, and Harry Belafonte. She was soon recognized for her stage presence, landing her first role in the Theatre’s production of “Our Town.” Four years later, she performed in her first Broadway show, “Lost in the Stars,” opening at the Music Box Theater in 1949.

Other Broadway roles followed in plays including “The Amen Corner,” “The Great White Hope,” and “Skin of Our Teeth.” She also had a small role in one of Tennessee Williams’ last Broadway plays, “Vieux Carré.” Though she had just two lines, she influenced Williams in creating her character, Nursie, a Black maid. Williams felt he couldn’t write authentically for a Black character, and sought Jeannette’s input throughout the rehearsal process.

Writing and Producing Plays

It was during this period she also began directing and producing her own plays. Struck by the absence of authentic Black characters on the stage and parts she knew she wouldn’t play, Jeannette began writing plays in the 1950s “about women, and strong women, that I knew no one would be ashamed to play.”

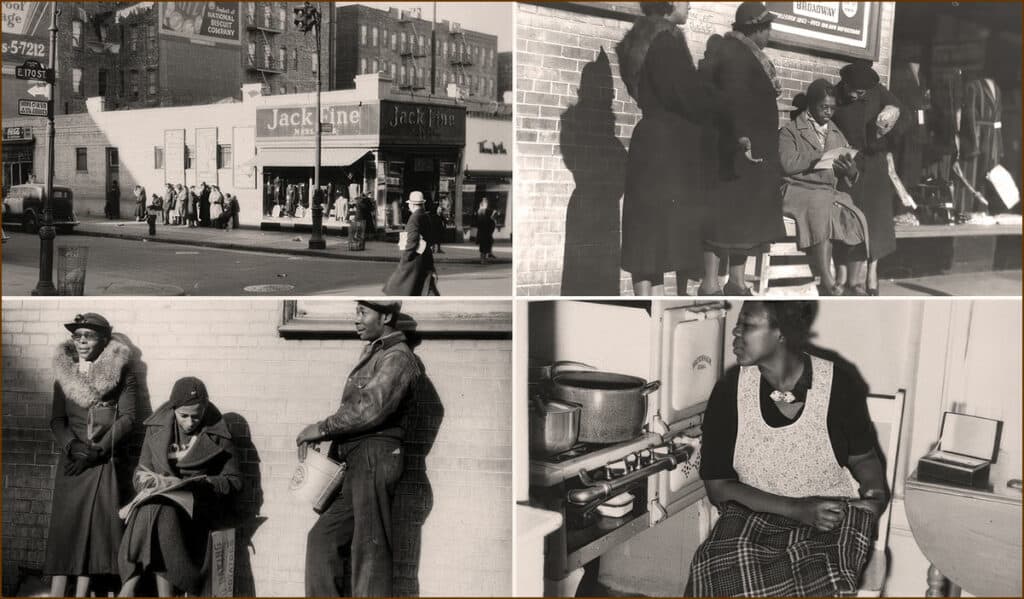

As a director, she mentored a generation of Black actors in New York, writing five plays that tackled racism, politics, family ties and the importance of education head on. One of them, “A Bolt From the Blue,” focused on what was called the Bronx Slave Market — groups of Black women who huddled outside department stores hoping for jobs as day laborers or domestic workers in the 1930s and ’40s.

Gertrude Jeannette made the leap from Broadway to early television and the silver screen in 1950 when she replaced Pearl Bailey in a CBS General Electric Hour production of James Weldon Johnson’s “God’s Trombones.” In the mid-1960s and 1970s, she appeared in popular films including “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” “Shaft” and “Black Girl.”

Civil Rights Activist

In addition to making a name for herself on the stage and screen, Gertrude Jeannette was also a civil rights activist. In 1949, she was at Peekskill, some 50 miles outside New York City, when the Ku Klux Klan arrived to lynch singer, actor and activist Paul Robeson, who was scheduled to appear at an open-air concert. Her husband and his motorcycle club, the Harlem Dusters, were there to help with security. The Klan hung Robeson in effigy, lit burning crosses on the open field and clashed with attendees before Jeannette and her husband rushed to their motorcycles to help get Robeson out of harm’s way.

Harlem’s American Negro Theatre closed its doors in 1951 after just 11 years. By then, many Black actors had moved to Hollywood while others, including Gertrude Jeannette, were barred from working during the Red Scare of the 1950s. She always believed she was singled out because of her association with Robeson. But that didn’t stop her.

Determined to stay put, she founded a series of community theaters throughout Harlem with the goal of developing local theatrical talent and enriching the community’s cultural life. Of those, the best known, founded in 1979, was the Harlem Artists Development League Especially for You Players, or HADLEY — which was her maiden name. The HADLEY, according to the 2010 Harlem Travel Guide, continues to bring professional theater at reasonable prices to the community so entire families can experience dramas, mysteries, comedies and educational theater.

Still Directing at Age 98

Gertrude Hadley Jeannette enjoyed a remarkable 70-year career on stage, in film and on television. She continued to act into her 80s, and retired from directing at age 98. She was 103 years old when she died at her home in April of 2018, having survived her husband by 62 years. She is survived by 10 nephews and six nieces. At her request, she was cremated; the location and disposition of her ashes remains unknown.

She received many awards during her career, one of which was the Outstanding Pioneer Award from AUDELCO in 1984 — the Audience Development Committee was established to honor excellence in African American theater in New York City. She was named AT&T and Black American Newspapers’ Personality of the Year in 1987. In 1991 she was honored as a “Living Legend” at the National Black Theater Festival in Winston-Salem NC. The Manhattan Section of the National Council of Negro Women bestowed their Harlem Business Recognition Award upon her in 1992. Six years later, she received the Lionel Hampton Legacy Award. She was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 1999.

Paul Robeson Award

And in 2002, she received the Paul Robeson Award from the Actors’ Equity Association. Created in 1971, the award honors “individuals that best exemplify and practice the principles to which Mr. Robeson devoted his life: dedication to universal brotherhood of all humankind, commitment to the freedom of conscience and expression, belief in the artist’s responsibility to society, respect for the dignity of the individual and concern for and service to all humans of any race or nationality.” Previous recipients included American Negro Theatre alumni Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis and Sidney Poitier.