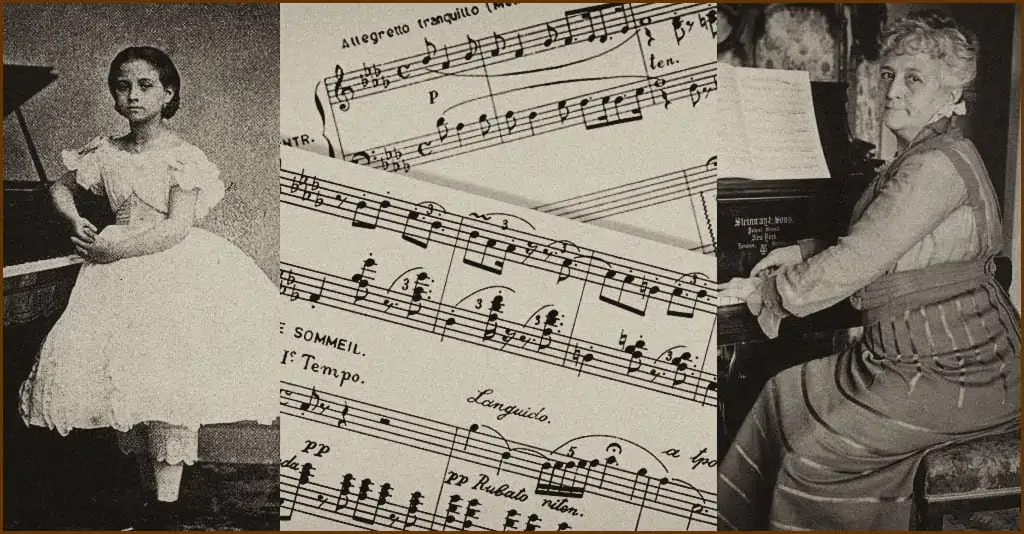

Music gave us The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, The Duke and, of course, The Boss. But long before Elvis swiveled his pelvis, Ellington tickled the ivories and Springsteen picked up the guitar, the music world was captivated by The Valkyrie of the Piano.

Born in Caracas, Venezuela in 1853, María Teresa Carreño García de Sena was a pianist and composer. She was considered the world’s supreme female pianist and one of its most popular touring artists. Her remarkable career spanned 54 of her 63 years, during which she toured the world and composed some 75 works for solo piano and voice, choir and orchestra, and chamber groups.

Known for her boundless energy and unbridled passion, her stage presence was said to leave audiences breathless. In fact, it was that energy and passion that led to her being nicknamed the Valkyrie of the Piano. Pianist Claudio Arrau, himself a South American child prodigy, recalled his joy in hearing her perform, exclaiming, “Oh! She was a goddess!” During her career, some of the most prominent musicians of her time sang her praises — Gounod, Rossini, Liszt, Berlioz, Brahms and a young Rachmaninoff among them.

Given her first piano lessons by her father, a politician and amateur pianist, Carreño practiced “two hours in the morning and two in the afternoon, and the rest of the day I played with my doll.” But when the family was exiled in a change of regime during Venezuela’s five-year Federal War, they immigrated to New York in 1862, where she studied with Louis Moreau Gottschalk, America’s first pianist to achieve international acclaim. Ironically, her new home was soon torn apart by another conflict — America’s Civil War.

By the time she arrived in New York, Teresa Carreño had been playing private concerts for years. But Gottschalk quickly recognized her talent; he began actively promoting her, encouraged her to perform, and even helped arrange her debut in New York City’s Irving Hall in 1862 when she was just nine years old. Dwight’s Journal of Music provides a wonderful description of the event: “Little Miss Teresa Carreño is indeed a wonder. A child of nine years, with a fine head and face full of intelligence, rather Spanish-looking, runs across the stage of the great Music Hall, has a funny deal of difficulty in getting herself up onto the seat before the Grand Piano, runs her fingers over the keyboard like a virtuoso, then plays you a difficult Nocturne, with octave passages and all, not only clearly and correctly, but with true expression.”

Wonder child

She toured America as a wonder child following her debut with five New York concerts before hitting Boston, where she sold out a dozen more. In Europe, she became well known before her 13th birthday.

That same year, she performed for President and Mrs. Lincoln at the White House, where they were mourning the death of their son, later writing that the Lincolns were “so very nice” she forgot to be nervous about her performance. Fifty-three years later, she returned to the White House to perform for President Woodrow Wilson.

Carreño spent her teens in Paris, studying and performing throughout Europe before returning to Venezuela in her early 30s. In addition to composing and performing, she had also developed a mezzo-soprano voice good enough for her to take the stage in productions of Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni. With the second of her four husbands, who was a baritone, she organized and directed an opera company in Caracas. But it, like their marriage, was short-lived, collapsing after just two years.

Composer, pianist, singer, conductor

Given the time in which she lived, Teresa Carreño was remarkably versatile. She was a prolific composer in an age that was outwardly intolerant of female composers. If a featured opera singer was unavailable, or became ill, she took the stage and sang. And if a temperamental conductor didn’t show up, or walked out, Carreño picked up the baton.

As a composer, she focused on works for piano, publishing her first piece in 1863 when she was just nine years old. Known for her innovation, she incorporated the merengue, a type of Dominican music and dance, into her compositions, often as interludes between other larger sections of a piece. A perfect example can be heard in her piece Un bal en rêve, (A Dream Ball) with its dance-like feeling.

Considered the equal of any pianist, male or female, Carreño continued to tour and perform until 1917 when, during a stay in Havana, Cuba, she became ill and returned to New York. Her health continued to erode; she eventually developed problems with her eyesight which led to paralysis of the optic nerve.

Honorary pallbearers

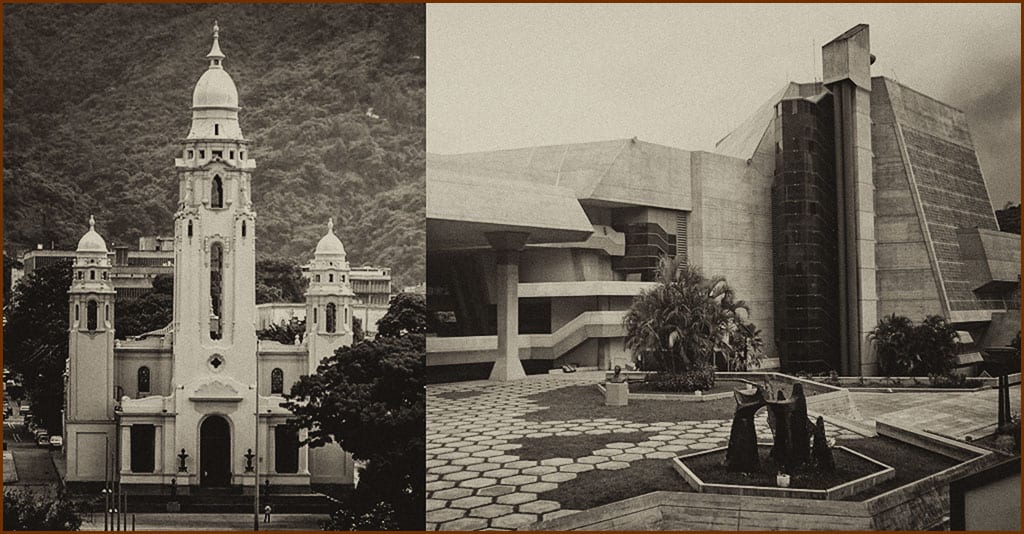

An American citizen, Teresa Carreño died at her New York apartment at the age of 63 in 1917. Honorary pallbearers at her funeral service included Ignace Paderewski (Polish composer and Prime Minister of Poland), Walter Damrosch (German-American conductor and composer and long-time director of the New York Symphony Orchestra) and Charles Steinway (amateur composer, pianist and CEO of Steinway & Sons). She was cremated and her ashes eventually repatriated to Caracas, where they lie in the National Pantheon, Venezuela’s resting place of national heroes.

Along with her professional brilliance, demanding career and hectic touring schedule, she lived a turbulent personal life that included four husbands — the fourth of which was the brother of the second, five children, and the pain of surrendering her first daughter for adoption, a decision she always regretted. All five children survived her, and were living throughout Europe at the time of her death.

Carreño also had a lasting impact on her native country. Today, Caracas is home to a sprawling performance space known as the Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex — the second largest and most important theatre in Caracas and Venezuela. Home to the Venezuelan Symphony Orchestra, it also houses some of Carreño’s historical correspondence, her musical scores and a collection of photographs.

Her only book, Possibilities of Tone Color by Artistic Use of Pedals, was published posthumously in 1919; she had been working on it at the time of her death two years earlier. But she is also the subject of a beautifully-illustrated children’s book titled Dancing Hands: How Teresa Carreño Played the Piano for President Lincoln, by Margarita Engle and Rafael López, published in 2019.

New York historical marker

If you’re in New York City, where West 96th Street and West End Avenue intersect, you’ll find a historical marker set into the corner of the Della Robia Apartments, Teresa Carreño’s home, commemorating her professional debut in Manhattan in 1862 and the 150th anniversary of her birth. And because this is the age of the Internet, she was also honored with a Google Doodle on what would have been her 165th birthday. There’s even a crater on planet Venus called Teresa Carreño.

Finally, her legacy as one of the world’s greatest pianists lives on through the biennial Teresa Carreño International Master Piano Competition, held in Miami Beach and sponsored by the nonprofit South Florida Friends of Classical Music. Open to pianists of all nationalities between the ages of 18 and 32, it provides one intensive week of concerts, master classes, and the contest itself, where competitors play for a renowned international jury of teachers and performers.

Lovely article about Teresa Carreño but I would like to clarify that the dance type in Un bal en reve relates to the Venezuelan merengue (not Dominican).

Thank you.

You would think, after a life in music, I would have known of this amazing lady. Until I read this article I had not, although I am familiar with all of the other musicians mentioned. Thank you Sandy. The contributions of women have been ignored for far too long. Wednesday’s Women is opening our eyes to some of them. Brava.