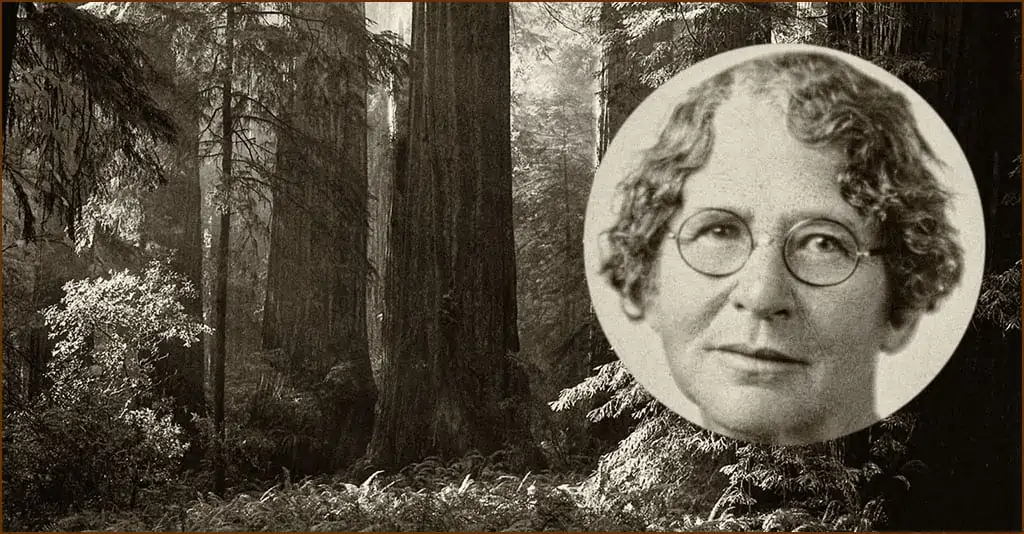

One of the most successful botanists and female plant collectors of her time, Ynés Mexía didn’t begin her career until age 55. Assertive, brave, and not afraid to knock the stereotypes of racism, sexism and ageism on their heads, she was remarkable not just for the number of specimens she collected, but for the number of miles she traveled to collect them.

In fact, she spent 13 years traveling the Americas, often alone, collecting close to 150,000 plants before she was done. A fierce conservationist, she was also a pioneer in the fight to preserve Northern California’s majestic redwood forests.

Exploring the outdoors

Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía was born in 1870 in Washington, DC, where her father served as a diplomat. A year later, the family moved to Mexia, Texas, a town founded by her ancestors. But when her parents divorced, her mother moved the family up and down the East Coast, from Philadelphia up to Ontario and back down to Maryland, where Mexía was packed off to boarding school. A shy, quiet child, she spent much of this turbulent period reading, writing and exploring the outdoors.

After completing her schooling, she considered entering a convent until her father asked her to come to Mexico to supervise his ranch and manage his household. He died in 1896, but Mexía stayed on, managing the ranch and the family business. Married twice, she lost her first husband suddenly after just seven years, and divorced her second.

She spent almost 30 years in Mexico. But in 1909, at age 39, she began showing symptoms of both physical and mental illness, known then as a “nervous breakdown.” Her doctor suggested she move to San Francisco, where she was treated by Dr. Philip King Brown at his Arequipa Sanatorium — a tuberculosis treatment center created for working-class women, for 10 years.

Save the Redwoods League

At Brown’s urging, she became an early member of the Sierra Club and Save the Redwoods League, hiking through the forests, camping in the National Parks, and nurturing a passion for plants and nature that likely had its roots in those long hours spent outdoors as a lonely young girl. And when she learned about the clear cutting of Northern California’s redwood forests at Montgomery Woods, her determination to save these majestic landscapes put her at the forefront of America’s national park conservation movement.

It was her passion for conservation that led her to enroll at the University of California Berkeley in 1921 at the age of 51 — a decision that’s uncommon today, but was absolutely unheard of for any woman at that time, especially a woman of color. After all, it was a time when, as historian Pamela Henson puts it, “male scientists objected to women in the field because they feared they would lower the level of scientific discourse.”

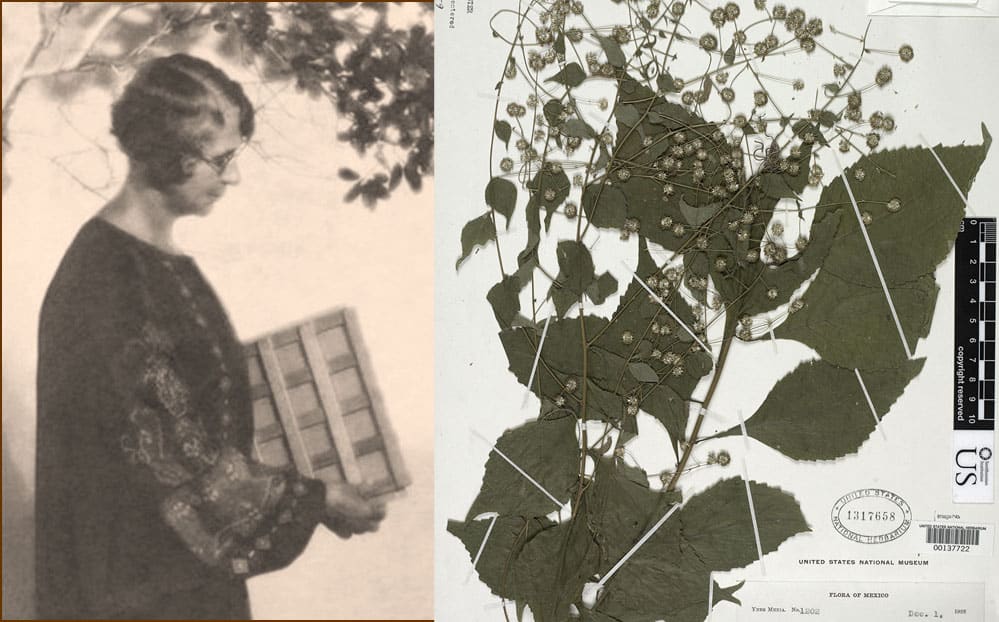

While Ynés Mexía took classes mainly in science and natural history, it was a university expedition led by a Berkeley paleontologist that introduced her to botany — the study of plants, and sparked her desire to collect and categorize plants and conduct intensive field work. Soon after, she was invited to join what was the first of her field collecting trips to Mexico in 1922 as part of a team organized by Stanford University. But she quickly realized she could get more done on her own, abandoning the group and collecting independently.

It took several years but finally, at age 56, she secured enough funding from other institutions to conduct her own expeditions with local guides into Mazatlán and the Sierra Madre Mountains. As her reputation as the first Mexican American female botanist grew, so, too, did her list of sponsors and the funding that led to a short, but prolific, 13-year career.

Alaska to Tierra del Fuego

Mexía continued to explore, from the northern reaches of Alaska, through little-known regions of North and South America, Brazil, Peru, Chile and Ecuador, to the tip of Tierra del Fuego. One of the highlights of her expeditions was canoeing the Amazon River from its delta in Brazil to its source high in the Andes — a trip that covered almost 3,000 miles and took two and a half years.

Some found her habits in the field surprising, clearly not befitting an early 20th-century woman. She traveled alone; rode horseback; wore trousers; and preferred to sleep under the stars even when indoor accommodations were available. During one trip to the “uninhabited and precipitous” foothills of Cruz de Vallarta, Mexico, she stayed at the hut of a local wood cutter, choosing to set up her cot in his banana patch.

Staunchly rejecting societal, sexist stereotypes, she recalled, “A well-known collector and explorer stated it was impossible for a woman to travel alone in Latin America.” But once Mexía decided to “become better acquainted with the South American continent, [she figured] the best way was to make my way right across it.”

Trekking across South America, Ynés Mexía was proud of having “a job where I produce something real and lasting.” And, boy, did she produce. Over her 13-year career she collected more than 150,000 specimens, discovered and categorized over 500 new species, and had over 50 of those named for her.

Dangerous terrains, injuries

Seemingly fearless, she and a local guide traversed rough, dangerous terrains. Mexía once fell from a cliff, breaking ribs and injuring a hand; experienced an earthquake in the middle of the night; and, at one point, accidentally ate poisonous berries, becoming wracked with abdominal pain for which the indigenous people had a remedy: she was to stick a chicken feather down her throat until the berries came back up … which they did.

She seemed to have an almost personal relationship with the plants, once remarking, “My [plant] dryers get filled up; and still numbers of plants sit and look at me and announce they are waiting to be collected. It is terribly trying to a greedy collector like myself.” Her field accounts describe an embarrassment of riches as she wrote in 1926, “I found the luxuriance of the vegetation actually embarrassing. It was hard to know where to begin to collect and even harder to know when to stop.”

In 1938, while on her final expedition to Mexico, Ynés Mexía fell ill and had to abort the trip and return to the United States, where she was diagnosed with lung cancer. Just a month later, she was dead at the age 68. She left most of her estate to Save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club — a generous donation and part of her legacy today. William Colby, then-director of the Sierra Club, remembered her: “All who knew Ynés Mexía could not fail to be impressed by her friendly, unassuming spirit, and by that rare courage that enabled her to travel, much of the time alone, through lands where few would dare to follow.”

Thirty years after her death, Save the Redwoods League established the Ynés Mexía Memorial Grove at Montgomery Woods State Reserve in Mendocino County, California; that same year, Redwood National Park was established by Congress, preserving 58,000 acres of land.

A famed scientist

Although Ynés Mexía never bothered to finish her bachelor’s degree, botanists the world over know her name. Researchers still use her collections, housed in museums and universities across the globe. An early member of many important Bay Area conservation organizations, Mexía was a true pioneer — a woman of color, over 50, traveling the world alone as a botanist. She opened doors for women entering the fields of conservation and botany, proving what they could accomplish if given the freedom to experience the world and pursue their passions. And, at a time when many people believed a woman couldn’t travel alone, Mexía simply replied, “I don’t think there is any place in the world where a woman can’t venture.”