This is the tale of a rusty, dinged-up, century-old tinned Christmas pudding and how it wound up in the dark recesses of a family pantry in a seaport town on England’s south coast. It’s also the story of the 19th-century woman known as the Mother of Britain’s Royal Navy.

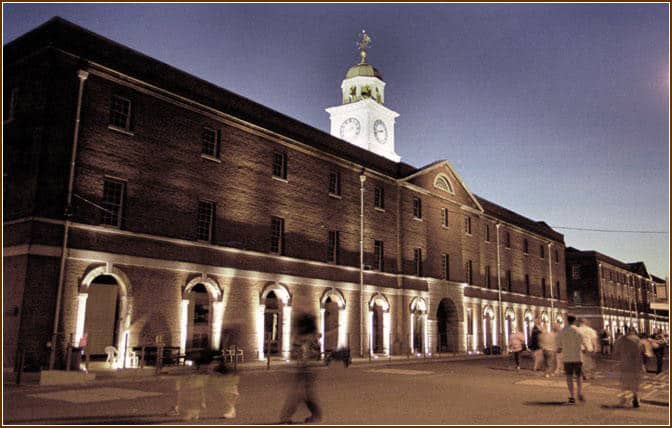

Navy Museum

In 2019, the pudding was displayed at the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. Thought to be one of 1,000 puddings made by Peak, Frean & Co, in 1899, it is the only extant example issued to the Navy and, according to the museum’s collections manager, may be “the oldest surviving Christmas pudding.” But the real story of how it wound up in that pantry belongs to a woman named Agnes Weston, beloved of generations of British sailors as just “Aggie,” The Mother of the Royal Navy.

Born in 1840, Agnes Weston grew up in comfortable middle-class surroundings as the daughter of a barrister. A headstrong, defiant girl when it came to accepting her parents’ Christian faith, she described church-going as being “90% hypocrisy and 10% sincerity.” But she eventually had a change of heart thanks to the teachings of a minister new to the family’s church in Bath. And, as with everything else in her life, when Weston accepted her new-found faith, she did so with a 100%, all-or-nothing commitment. She was determined to actively live her faith by helping others.

Sailors’ penpal

Her charitable path led to a Sunday school class of raucous boys the locals called “the unmanageables” — boys no one else would take on. But Aggie Weston took them on and was so successful in managing the heretofore unmanageables she was asked to find recreation facilities for some local militia troops. When those young men left England, Weston promised to write so they would have at least one link to home. When her list of pen pals became too much for her to handle by herself, she published a monthly newsletter called Ashore and Afloat, which she personally wrote until her death — by which time more than 55,000 copies were being distributed.

Her first link to the Royal Navy came when sailors on troopships saw the letters some of the soldiers were receiving and asked if she could write to them as well. Never one to turn down a heartfelt request, Weston obliged.

Sailors’ rest facilities

By the late 19th century, almost 4,000 young men were being trained by the Royal Navy, most of them away from family for the first time, wandering neighborhoods with nothing to do and no place to go but the pubs. But it was also a time when the British temperance movement was popular, with one out of every six men abstaining from drink. A staunch supporter of temperance and director of the Royal Naval Temperance Society in the 1870s, Weston prevailed upon a good friend to open her family’s home to the boys as a safe, comfortable, welcoming place to meet. Eventually, her idea became so popular she needed more space. So when a group of sailors asked her to provide what she termed a “sailors’ rest house,” she knew she had to find a way. After all, as Weston once said, “You don’t make a torpedo gunner out of a drunkard.”

More complex than any of her previous undertakings, Weston realized this would require some out-of-the-box thinking along with her characteristic all-or-nothing approach. She was determined to bring home comforts and wholesome entertainment to the sailors of the Royal Navy in England’s seediest dockyard cities. Naturally, society raised its collective eyebrows at something no respectable young lady from a professional home would have done. But Aggie Weston, never giving a fig for what society thought, jumped into her latest challenge with both feet.

Queen Victoria

Her single-minded dedication resulted in Sailors’ Rests becoming a presence in all the Royal Navy’s main bases, including several abroad. They became so popular local taverns closed in the face of her stiff competition, only to be taken over by Weston to give the seamen more space. The Rests were so valuable even Queen Victoria recognized them, bestowing her patronage and the much-coveted prefix “Royal” to the Sailors’ Rests. And after meeting Agnes Weston several times, the Queen named her a Dame of the Empire.

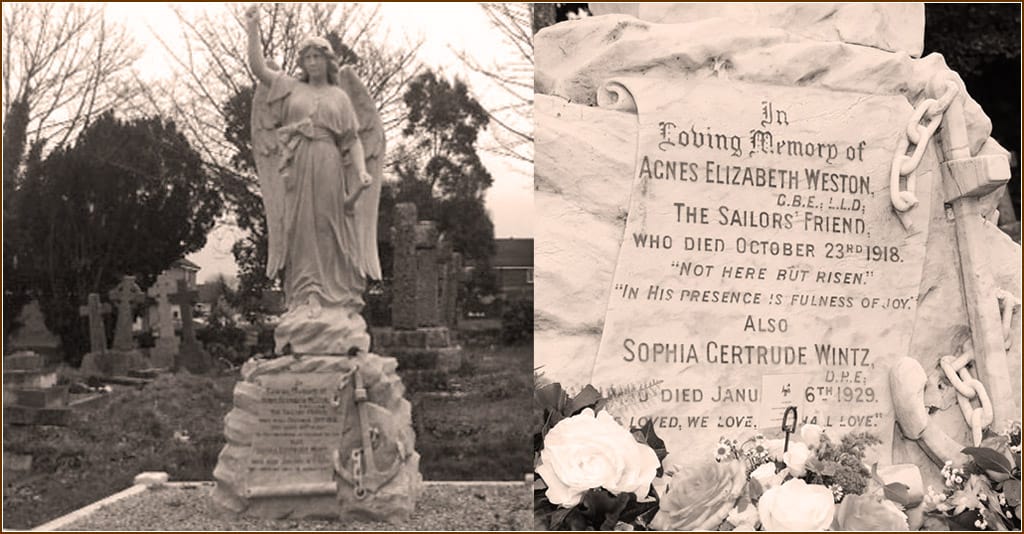

Dame Agnes Weston died in 1918 at the age of 78, shortly before the end of World War I, and was buried with full military honors — the first time such an honor was accorded a woman. More than 2,000 officers and enlisted men packed Plymouth’s Weston Mill cemetery to pay their respects. Known to generations of British sailors as the Mother of the Navy, she was more commonly and affectionately referred to simply as “Aggie.” So it seems only fitting that she lies beneath a gravestone identifying her as “the Sailors’ Friend.”

Order of the British Empire

That same year, her lifetime of work for the Royal Navy was publicly recognized when she was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE).

The independent Christian charity she founded in 1876, Dame Agnes Weston’s Royal Sailors’ Rests (generally known as Aggie Weston’s or just Aggie’s), remains active. Its latest financial report describes the Rests as “alcohol-free facilities providing a safe refuge and genuine alternative to the other less wholesome entertainment and housing facilities available outside a 19th-century dockyard.”

And as for that pudding? It was one of 1,000 Agnes Weston arranged to have sent to British naval personnel involved in land-based operations during South Africa’s Boer War in the belief that “a Christmas pudding for each man … would be a nice little present.” Though clearly inedible after more than a century, its decorative tin still offers instructions for preparation along with a holiday message:

“This pudding is ready for use but may be boiled for an hour if required hot. For the Naval Brigade, In the Front, With Miss Weston’s Best Christmas & New Year, 1900, Wishes.”

A similar middle class lady did the same for the British Army during the same period as ‘Aunt Aggie’. This was Miss Sandes, who was also appointed DBE. The largest pre 1918 Sande’s Soldier Home was in Ireland at the Curragh Garrison. After Irish independence the home moved to Ballykelly in Northern Ireland. Miss Sandes passed away here during the 1920s and is interred in a local churchyard. Both Aunt Aggie and Miss Sandes were pioneers and heroes of their day, obedient to the Lord’s teaching, they ministered their love and appreciation to the lower deck of the Royal Navy and the rank and file of the Army, showing thousands of lost sailors and soldiers the real character of Jesus Christ.

Thank you for sharing Aggie with us! Amazing story of how obedience to God’s calling of compassion can affect so many people for good. She saw a need and did something about it. May we be inspired to do so as well!