As a girl, Isabella Goodwin wanted to be an opera singer. So how did this wannabe diva wind up working with the New York Police Department to nab a motley crew of bank robbers and, in the process, become the Big Apple’s first female police detective?

Born Isabella Loghry in Greenwich Village, she married an NYPD patrolman named John Goodwin at 19. But he died after 11 years of marriage, leaving a 30-year-old widow with four children to support on her own.

Goodwin decided she, too, would work for the NYPD. And while it was not unusual for police departments to hire widows of fallen officers, Goodwin wasn’t just handed the job. She studied for and passed the civil service exam and, in May of 1896, was appointed a police matron.

The Role of Police Matron

In 1845, the American Female Reform Society fought for and won the appointment of two matrons at the Manhattan House of Detention (a.k.a. the Tombs) and four more at Blackwell’s Island Asylum, the country’s first municipal mental hospital. Their appointments marked the first official recognition of the idea that women prisoners could be handled by women.

After the assault of a young female prisoner in 1891, the job of police matron took on greater importance when commissioner Theodore Roosevelt expanded their duties to deal with female crime victims, sex crimes and cases involving children.

Known for Her Sleuthing Skills

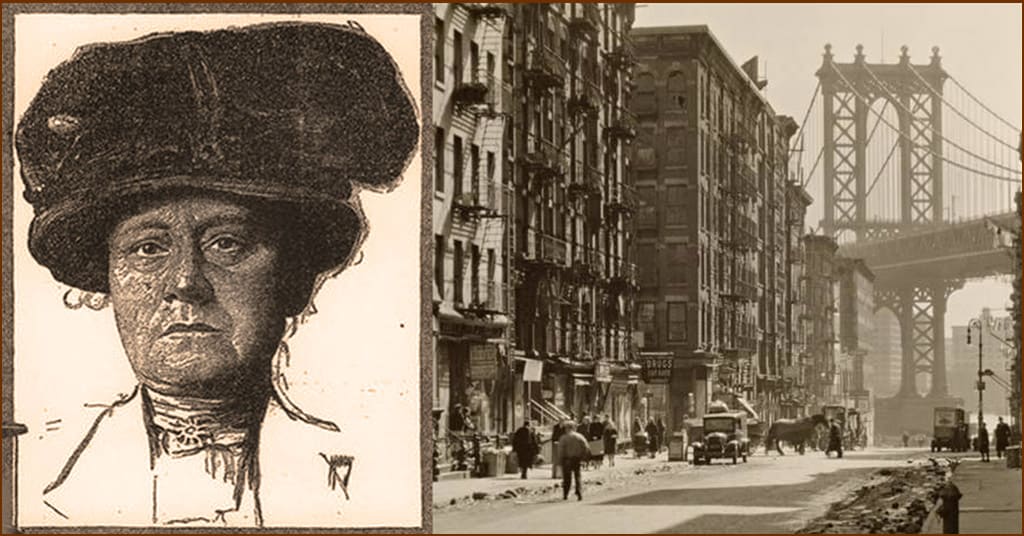

But even as a matron, Isabella Goodwin was known for her sleuthing skills. One contemporary newspaper account described her as having “a kind, motherly face. Her dark hair is not yet streaked with gray. And her gray eyes are full of expression and sympathy. A broad forehead denotes intelligence, and her whole manner would lead one to take her for a married woman of the well-to-do class.”

Standing just 5′ 1″, Goodwin put her kindly, sympathetic appearance to good use when the detective bureau tapped her to help with special investigations, posing as a naive society matron to expose fortune tellers, astrologers, Hindu magicians, quack healers and surgeons.

She even passed as a degenerate gambler to help raid women-only betting parlors. In all, she obtained evidence against over 500 swindlers while working as a police matron.

Eddie the Boob and the Taxi Cab Bandits

Isabella Goodwin’s life changed one morning in February of 1912 when a daring bank heist took place in broad daylight on a busy city street in the heart of Manhattan’s Financial District.

A stick-up man known as Eddie “the Boob” Kinsman and his accomplices hijacked a taxi, robbed the driver and his guard and beat them senseless before speeding away in a waiting getaway car with no license number. The East River National Bank heist netted them $25,000 — enough to pay about 30 annual salaries in New York City or buy 385 automobiles in 1912 — or today’s equivalent of about $677,200.

The robbery stunned Manhattanites and made national news when the robbers eluded seasoned detectives. With no breaks in the case and no whispers about who could have pulled off the “impenetrable mystery,” the press lambasted the NYPD as “seemingly helpless” in its inability to crack the case.

Then a rumor surfaced about two people who might know Kinsman’s whereabouts: “Swede Annie” Hull and her roommate, Myrtle Hoyt, both long known to the NYPD. When they learned Eddie the Boob was known to visit his sweetheart, Swede Annie Hull, in a seedy boarding house full of shady characters, they called Isabella Goodwin.

Making $1,000 a year as a police matron with no hopes to advance, and knowing a detective earned $2,250 a year, Goodwin knew an opportunity when she saw one, and took her first step up the ladder.

Undercover Maid of All Work

She went undercover to find Swede Annie, hiring on as a maid of all work — scrubbing floors, cleaning rooms, collecting rent, emptying garbage, running errands for lodgers and cooking meals — for $6 a week. In return, she would live rent-free in a “dark, wretched little hole under the stairs.”

Interviewed by the NY Times, Goodwin explained how she dressed the part “with slatternly clothing and frowsy hair.” Wearing an old kimono from home as she worked, Goodwin watched the lodgers by day and, fueled by strong coffee, roamed the halls at night, standing outside doorways, listening at keyholes, and sneaking out in the wee hours to report back to the NYPD.

It was through one of those keyholes she heard Swede Annie tell her roommate, “Well, Eddie the Boob turned the trick, all right.”

Myrtle Spills the Beans

Goodwin knew from her years as a matron that down-on-their luck women often confided in the hired help. So when she saw Myrtle Hoyt fuming in their room a week later, she asked one simple question: “What’s wrong?”

By the time Hoyt stopped talking, Goodwin had learned Eddie the Boob Kinsman and Swede Annie Hull had been on an upstate shopping spree. When Hull returned in fancy new clothes and flashing a wad of money, she told Hoyt she was moving out, and that she and Kinsman were staying in a downtown hotel before heading for California.

Thanks to Isabella Goodwin, four NYPD detectives were waiting at Grand Central station to arrest Eddie the Boob Kinsman as he was about to purchase two tickets west. He was charged with highway robbery and assault with attempt to kill and was eventually sentenced for three to six years.

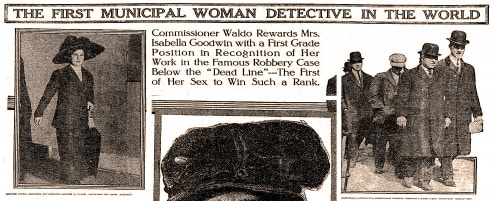

The morning after his arrest, Goodwin was called to the commissioner’s office and upgraded to the rank of detective lieutenant with a hefty salary bump to $2,2500 a year. Not only had she become the NYPD’s first female detective, but The Brooklyn Daily Eagle proclaimed her “the best known woman sleuth in the United States.”

Legacy

In 1918, NYPD brought its first six police women into the squad. Paid $1,200 a year, they were issued handcuffs, a revolver and a summons book — but no uniforms. Three years later, Goodwin was picked to lead the department’s new Women’s Bureau, a division of 26 female officers charged with overseeing cases involving prostitutes, runaways, truants, and victims of domestic violence. And in 1924 she worked with prosecutors investigating fraudulent medical practices to help clinch several high-profile arrests before retiring later that year.

By the time she retired, Isabella Goodwin had spent 30 years with the NYPD, helping serve and protect generations of New Yorkers. But she benefited from her years of service as well, saying, “Oh, the things I have learned about poor, weak human nature! My experiences would fill a book.” Which they did in 2011, when The Fearless Mrs. Goodwin: How New York’s First Female Detective Cracked the Crime of the Century was written by Elizabeth Mitchell.

Today there are about 6,570 women on the NYPD’s 36,500-member force, or about 18%. They include 781 detectives, 753 sergeants and 200 lieutenants. Goodwin once said women made strong detectives thanks to their ability to “sense things for which at first you have no actual proof” — in other words, women’s intuition — but added she was proud to show “just what a woman can do when the chance comes her way.”

Isabella Goodwin died of colon cancer in October 1943 at the age of 78. She is buried in Brooklyn’s famous Green-Wood Cemetery, founded in 1838 as one of America’s first rural cemeteries, under the name Isabella Seaholm, reflecting the name of her second husband.

Terrific story worth more reading. I learned of her for the first time while reading “Death of A Showman” (novel) by Mariah Frederick containing a one-line reference to Goodwin !