The future Emilia Casanova de Villaverde was a willful, headstrong teenager and never one to hold her tongue. She lacked the “coquettish manners believed to be natural in young women.” But what she had was a fire in her belly for Cuban independence in the late 19th century when Cuba was still governed by Spain. So much so that at a convivial banquet attended by Spanish authorities, she rose to lift her glass in a very public toast “to the freedom of the world and the independence of Cuba.” Talk about knowing how to clear a room.

One of 16 children born into an elite, conservative, slaveholding Cuban family in 1832, she distanced herself from her family’s views at an early age. The Casanova household was often thrown into a state of chaos because of her determination to pursue pet projects and what the family called “whims.”

At the age of 18, Cuban independence became her one purpose in life and the channel for her considerable energy — not to mention a huge headache for her family which, thanks to their daughter’s public criticism of Spanish rule, found themselves under increasing scrutiny from colonial authorities.

Coming of Age in New York

Fearing political retribution, Inocencio Casanova decided to relocate his family to the United States. He chose New York City. In 1850, Manhattan was home to a little over 200 Cuban immigrants. And while merchants had established the core of New York’s Cuban community, the island’s revolutionaries, exiles and intelligentsia made Manhattan the primary staging ground for the building of the Cuban nation. Her three months there in 1852 had a profound impact on Emilia Casanova. It was her first exposure to the Cuban exile community and its leaders; before she left, they gave her a secret stash of subversive pamphlets and documents, all of which she read.

Eventually, the Casanova family settled in Philadelphia, where Emilia, age 22, met lawyer, author and Cuban exile Cirilo Villaverde, 20 years her senior. In 1849, Villaverde was arrested and condemned to death for his involvement in a conspiracy to overthrow the Spanish government. He somehow escaped, fleeing to the United States. In what seemed to be a match made in heaven, Emilia and Cirilo married in 1854 and, after her family returned to Cuba, they moved to New York. There, she quickly became immersed in the exile community, organizing meetings and opening their home to friends of the revolution.

Arsenal Under Bronx Mansion

She eventually convinced her father to liquidate his assets in Cuba and return to New York in 1867. For $150,000 (about $5 million in today’s currency), Ignacio Casanova bought a baronial mansion in what is now the Hunts Point area of the Bronx, complete with a vast network of underground tunnels and vaults originally used to store wine. But Emilia Casanova de Villaverde had other ideas. The mansion soon became a hotbed of militant activity for Cuba Libre, its vaults serving as storehouses for guns, rifles, powder and ammunition. Set on 50 acres, fairly isolated, and near the coast, it was perfectly suited for smuggling ordnance out to the East River or Long Island Sound for shipment to Cuba.

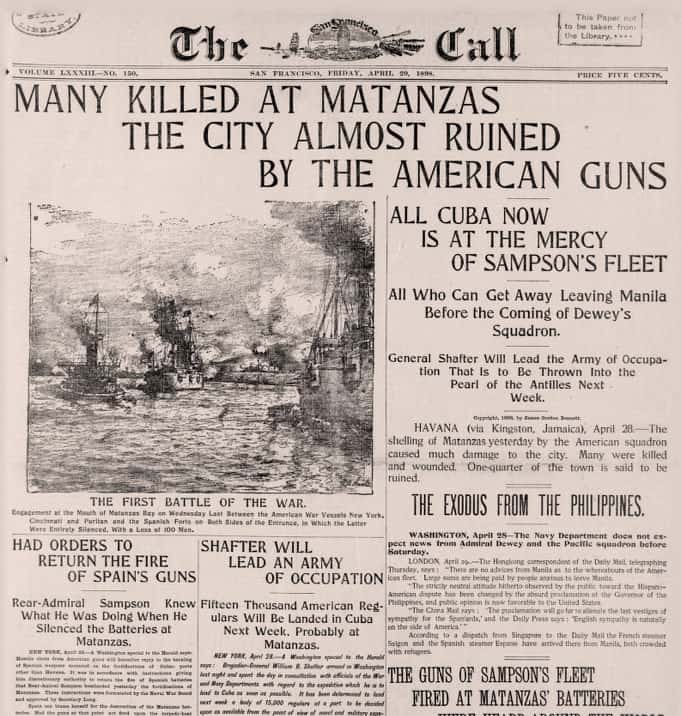

In 1868, Cubans and Puerto Ricans rose up against Spain in the quest for freedom. And although Puerto Rico’s uprising was easily quashed within 24 hours, Cuba’s revolt marked the beginning of a Ten Years’ War that engaged more than 12,000 freedom fighters.

As the revolution raged on her native island, Casanova de Villaverde formed one of the first political organizations created and directed by women of New York — La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba (The League of the Daughters of Cuba). While it raised money to sustain the elderly, widows, and orphans seeking refuge from the war, its main objective was to gather resources of all kinds to aid Cuban fighters. As Casanova de Villaverde makes clear in her letter to General Manuel de Quesada, the Cuban rebels’ Chief of the Armed Forces: “… the purpose I write is to inform you that the next shipment of arms and ammunition has been sent by The League of Daughters of Cuba.”

In 1878, with about 200,000 casualties, the Ten Years’ War ended without Cuban independence, with Spain promising reforms and the abolition of slavery. Casanova de Villaverde and her husband remained in Manhattan where, in 1880, the U.S. Census placed them in Harlem, across the street from the rest of her family. It was there, with his wife’s help, Cirilo Villaverde completed his classic Cuban novel, Cecilia Valdés. Described as “a vast landscape of the moral, political, and sexual depravity caused by slavery and colonialism,” the work is now considered the most important Cuban novel of the 19th century.

Rhetoric, Guns and Money

Cirilo Villaverde died in 1894. To honor his wishes, Emilia traveled briefly to Havana to bury him in the city’s Colón cemetery, where he joined notable poets, novelists, musicians, soldiers and statesmen. She returned to New York just at the time when Cuban leaders from the failed Ten Year’s War took up arms in a renewed attempt at independence. Casanova de Villaverde’s support, with both words and firepower, of this new war against Spanish control of the island never wavered. According to correspondence from that period, she was stockpiling Winchester carbines and ammunition in her midtown Manhattan home to send to Cuba, just as she had done 25 years earlier at the mansion on Hunts Point.

Just three years later, at the age of 65, Emilia Casanova de Villaverde died without realizing her dream of an independent Cuba. Twenty years younger than her late husband, she survived him by only three years. She was buried in Old St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx until 1944, when her son fulfilled her wish to be laid to rest next to her husband.

She Died, But Her Dream Succeeded

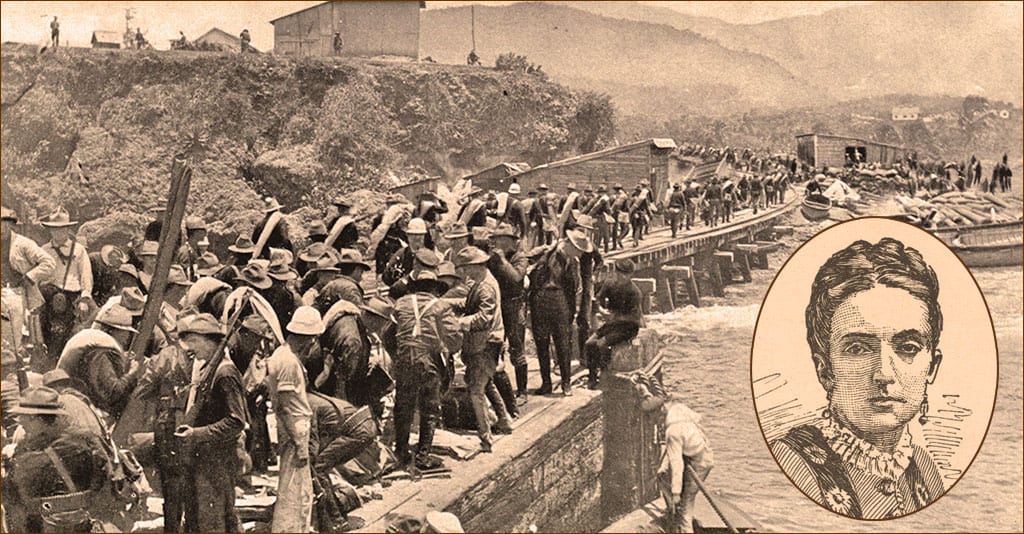

Seventeen months later the revolution she had helped so effectively to foment succeeded. U.S. troops, including Teddy Rosevelt’s “Rough Riders,” joined with Cuban revolutionary brigades to drive the Spanish overlords out.

A Cuban patriot and exile who lived most of her life in New York City, Emilia Casanova de Villaverde was the first Cuban woman to write political essays. She addressed the United States Congress, representing Cuban women fighting for independence. And when her father was being held a political prisoner of Spain in Cuba, she personally appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant for his release. For her efforts, she was denounced in the conservative press, viciously attacked and pilloried in political cartoons, and even burned in effigy in her hometown of Cárdenas, just outside Havana.

Today, the land where the baronial mansion known as the “Cradle of Cuban Liberty” once stood houses a hub of the largest wholesale food markets in the world. But back in the day, neighbors knew about the secret activities going on. Years after Inocencio Casanova abandoned the mansion, leaving it deserted, as Bronx historian Stephen Jenkins writes, there were “whispers of murdered Spanish spies and ghosts and strange, unaccountable noises in the vacant house … so much so that its demolition was watched by the locals with intense interest.”

And not far away, a Bronx public school is named for “a Cuban patriot who aided in the early Cuba revolution by supplying munitions sent to Cuba from the Casanova mansion.” But its namesake is not Emilia Casanova de Villaverde … it’s her father, Inocencio Casanova, the millionaire.

No biographies have been written about her father; he leaves no papers behind; his greatest accomplishment may be that he fathered the woman who is a giant in the pantheon of patriotic Cuban women because of her work in New York. Today, biographies of Emilia Casanova de Villaverde, along with papers from La Liga de Las Hijas de Cuba, are found in the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami Libraries and are available to researchers at the Library of Congress.

Maybe school officials didn’t know the story of Emilia Casanova de Villaverde when they named P.S. 62 in 1922; or perhaps they chose not to name the school after a woman. But for the students of P.S. 62, whose enrollment is 80% Hispanic and 17% Black, I can think of no better example of courage and determination than the story of the true Cuban patriot whose lifelong struggle was for Cuban independence and the abolition of slavery on her native island.