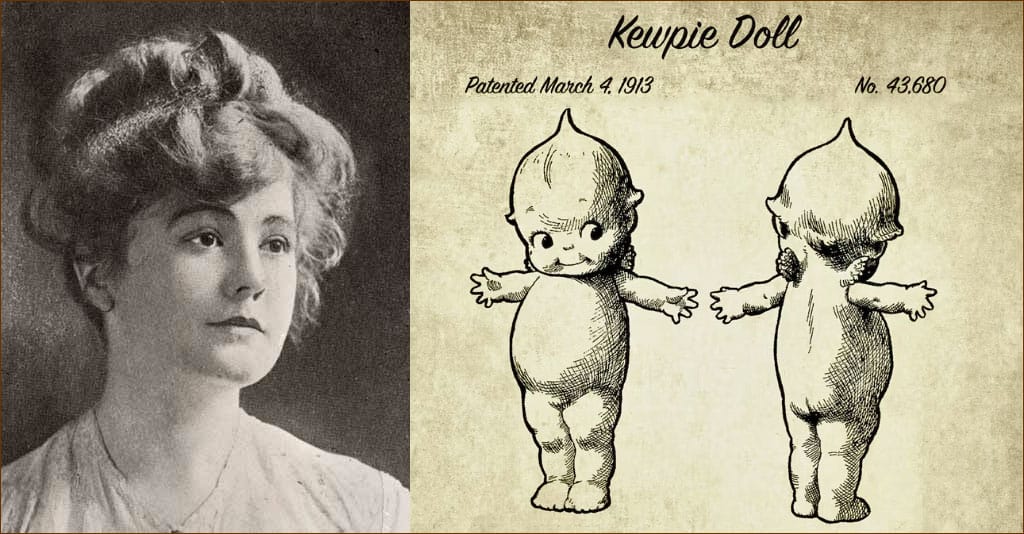

Cecelia Rose O’Neill was many things … self-taught artist and sculptor, author and poet, suffragist and, for a time, one of the world’s richest women. But to most people, she was the woman who birthed “The Kewpies” — plump little cartoon characters and world-famous dolls with top knots, rosy cheeks, broad smiles, and sidelong eyes. Debuting in 1909, Kewpies were the world’s most widely known cartoon character until a guy named Disney introduced us to a cheeky mouse named Mickey in 1928.

Celtic Lore and Legends

Born in Pennsylvania in 1874, O’Neill was one of six children. Her father was an itinerant bookseller, her mother a gifted musician and teacher. The whole family went West by covered wagon when she was little, settling in rural Omaha, Nebraska. Though they lived in poverty, O’Neill’s world was rich in Celtic lore and legends told to her by her Irish father. What she lacked in formal education she made up for by poring over library books and her father’s extensive library, studying classic Greek mythology and Renaissance engravings.

She started drawing at age 13, winning a drawing contest for the Omaha World-Herald in her hometown. By the time she was 18, and with no formal art education, newspapers and magazines across the Midwest were publishing her drawings. Within a year, she traveled alone to New York, full of hopes and dreams of becoming an artist and selling a novel. She also brought with her a portfolio of 60 illustrations and sketches she shopped around to Manhattan magazine editors and publishers. They admired her work so much they gave her commissions for illustrations and commercial posters. O’Neill’s career as a professional artist had officially begun.

New York Superstar

Settling into Manhattan, she soon made a name for herself; for more than five decades, her work would be published in national magazines like Life, Ladies’ Home Journal, Collier’s, Woman’s Home Companion and Harper’s Monthly. But her greatest contribution was to America’s leading humor magazine, Puck.

Along with its colorful cartoons, caricatures, and political satire on issues of the day, they published over 700 of her illustrations.

At 23, she became its first female staff artist, earning top dollar for her work. She was also a savvy businesswoman who knew her worth long before “know your value” became a catch phrase for female entrepreneurs — she insisted on retaining the rights for all her illustrations, meaning the originals were always returned to her.

Highly sought after as a cartoonist, illustrator, poet, and short story writer, her work appeared in over 50 magazines and her illustrations graced the covers of 60 national publications. Companies like Proctor & Gamble, Colgate Palmolive, Jell-O, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Oxydol, the Rock Island Railroad, and Edison Phonograph hired O’Neill to create illustrations for their advertising campaigns.

Gender Tension

Her successful career as an illustrator was unprecedented in a male-dominated field. So much so, she was initially encouraged by publishers and editors to hide her gender from the public. But by 1896 she was hailed as “America’s First Female Cartoonist” by Truth Magazine for her comic strip “The Old Subscriber Calls.” But commercial success seems to have come with a price. After two marriages and divorces during this period, O’Neill decided to remain single after 1907.

Family Move to the Ozarks

While she was busy forging a career in New York, O’Neill’s family moved from Nebraska to a rural farmstead in the Missouri Ozarks. The first time she visited, it was love at first sight — she was enchanted by the rolling hills, woods and streams. More importantly, she was inspired, for it was in this magical place she first envisioned and created the chubby, dimpled, top-knotted cupid-like characters that would make her famous the world over. Her income allowed her to build her family a 14-room, three-story home she named Bonniebrook. It was a place O’Neill returned to time and again throughout her busy life and, near its end, she would retire there.

Rise of the Kewpies

In 1907 O’Neill began writing short stories featuring cherubic characters who “did good deeds in a humorous way.” She described them as “a sort of little round fairy whose one idea is to teach people to be merry and kind at the same time.” Her comic strip called “The Kewpies” premiered in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909 and was an instant hit with both children and adults, inspiring O’Neill to envision the Kewpie as a doll.

Four years later, in 1913, she patented a doll based on her Kewpie character, personally overseeing the making of the first Kewpie doll. Originally produced in Germany as bisque dolls by German toy company J. D. Kestner, composite and celluloid versions soon became available. Kewpies were so popular, factories in six different countries were needed to keep up with orders. And much like Barbies would be sold in the 1950s, Kewpie dolls were marketed worldwide along with all manner of Kewpie merchandise, including fabrics, trinkets, and tableware.

First Novelty Toy Distributed Worldwide

O’Neill’s Kewpie doll became one of the first mass-marketed toys in America and the first novelty toy distributed worldwide, earning her a fortune. It was also the most popular and well-known cartoon character until Walt Disney introduced his mouse named Mickey in 1928’s animated short film titled “Steamboat Willie.”

Successful beyond O’Neill’s wildest dreams, the Kewpies amassed her a fortune. As The New Yorker’s Alexander King wrote in a 1934 piece about the Kewpie: “Almost immediately, it became the national dream child and for years remained the most popular piece of American sculpture, making, it has been estimated, more than $1,400,000 (roughly $32 million today) for Miss Rose O’Neill.”

What King overlooked was the fact that O’Neill’s innocent little Kewpies gave her a platform from which to comment on issues like women’s rights and discrimination. She also used her art and philanthropy to champion the downtrodden, having experienced firsthand the indignity of poverty.

Highest-Paid Female Illustrator

By 1914, Cecelia Rose O’Neill was the highest-paid female illustrator in America. Her income allowed her to comfortably support her large family in Missouri while she traveled extensively throughout Europe, befriending fellow artists and writers and throwing posh parties.

But it was also a period where she remained dedicated to her own creativity and art. As a sculptor and painter, she exhibited serious works in both New York and Paris. And as a novelist and poet, O’Neill published eight novels and several children’s books.

Lavish Lifestyle

A lavish spender, she owned properties that included Bonniebrook in the Ozarks and an apartment in Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village (where it’s said she inspired the song “Rose of Washington Square”); a villa in Connecticut she named Castle Carabas (after a favorite Puss ‘n’ Boots character); and Villa Narcissus on the Isle of Capri, Italy.

King’s 1934 piece in The New Yorker described how “guests invited for a weekend remained two years,” writing, painting, sculpting, and playing intellectual games led by O’Neill and of how “her legendary generosity became the keynote of her life and, today, at sixty, remains her greatest charm and most fatal indulgence.” She seems to have entertained and supported a literal “Who’s Who?” of artistic talent, among them Martha Graham, Kahlil Gibran, Isadora Duncan, Eva Gallienne and Booth Tarkington.

“Sweet Monsters”

It was also in this eclectic environment that she produced what she called her “Sweet Monsters.” Drawing on European artists and her own Irish-American heritage, O’Neill created dark mythical figures with unsettling animal traits, stretching and pulling them into extreme, sometimes sensual poses in paintings and sculptures. For fans who had come to love O’Neill for her adorable Kewpies, her fine art exhibits in Paris and New York revealed an entirely different side to her artistic leanings that enthralled, challenged, and sometimes repulsed them.

As O’Neill herself wrote, “There are some people who find some of my pictures revolting; they hurt the eye. …. The buffoonery of the Kewpie dolls and the passion of my serious drawings playing side by side is unusual. But not too unusual.” It’s a duality that suggests the conflicting beliefs we hold about dolls in general. As cute and endearing as they may be to some, to others they’re creepy, disturbing creatures hiding behind dimples, big eyes, and endearing ringlets.

The Decline

In the 1930s O’Neill’s fortunes began to dwindle due to her extreme generosity and lavish spending coupled with the effects of the Great Depression. Plus, her Kewpies were getting old … after 30 years, they were no longer in demand at a time when realistic photographs were replacing fanciful illustrations in the media.

By 1939 the money was all but gone. O’Neill found herself broke at the same time she was heartbroken after her mother’s death. She retreated to Missouri in 1941 to live with her family, where she began writing her memoirs with the help of friend and Ozark folklorist Vance Randolph.

Her Passing

Cecelia Rose O’Neill died at her beloved Bonniebrook three years later, having suffered a series of strokes and congestive heart failure. Sixty-nine years old and penniless, she was laid to rest in the small family cemetery at her family’s homestead.

The rambling, three-story, 14-room home completed by the family and local craftsmen on the remote, rustic setting that so captured O’Neill’s heart was destroyed by fire in 1947, the property quickly becoming wild and overgrown.

Twenty years later, the Rose O’Neill Club was founded to preserve her memory. In 1975 it became the Bonniebrook Historical Society, and work began to build a replica of the house. Completed in 1993, it is now a home and museum housing O’Neill’s archives and memorabilia, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Her Honors

Cecelia Rose O’Neill was selected as a member of the prestigious Société des Beaux Arts in Paris in 1906. She was the first woman elected as a Fellow of the New York Society of Illustrators and inducted into the Illustrators Hall of Fame in New York City in 1999. She was also inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2019. And last year, at the San Diego Comic Con, she was inducted into the Eisner Awards Hall of Fame as a Comic Pioneer.

Both the Smithsonian Institution and the New York Art Resource Consortium maintain digital online archives of O’Neill’s work. And you can find a large collection of her original work at the Huntington Library in California.

O’Neill’s Legacy

Rose O’Neill wasn’t just a pioneer in the field of comics. Known to the National Women’s Suffrage Association in New York City as a “Suffrage Artist,” she used her creativity to advance the cause of women’s rights. She marched as a suffragist and illustrated posters, post cards and political cartoons for the cause. She also championed dress reform, turning social morés on their head by brazenly going uncorseted under the loose caftans she wore in her studios!

She was the very definition of the self-taught bohemian artist. She rose through a male-dominated field to become a top illustrator and built a merchandising empire from her work thanks to the Kewpies. She redefined what it meant to be a 19th century female artist, showing other young women through her life’s work what could be achieved not just creatively, but commercially.

She seems to have been a beautiful if melancholy soul. Ambitious, talented and, for a time, one of the wealthiest women in the world, her autobiography, published years after her death, revealed her personal philosophy:

“Do good deeds in a funny way.

The world needs to laugh or at least smile more than it does.”