Over her lifetime, Dorothea Lynde Dix became a famed advocate for more humane and effective treatment of mental illness in the United States and Europe. When she began her life’s work in the first half of the 19th century, victims of mental illness were viewed with fear and annoyance; the only solution was to “put them away” in hellish lunatic asylums. By the time she died in 1887, Dix had touched countless lives with campaigns that moved state and federal governments to begin recognizing mental illness as an illness rather than a moral weakness.

Back then, before today’s science had developed a more sophisticated understanding of the ailment, mental derangement was thought to be caused by things including “disappointed affection,” loss of property, fatigue and excitement, intemperance, masturbation, overwork, “long-continued womb trouble,” an unhappy marriage, operation for hemorrhoids, and “suicidal menopause. It as even believed that the drift into lunacy — much like the rise of the tides — could be caused by the pull of the moon.

Her own physical illness

Although she ultimately achieved major national change in this field, her own life was a gauntlet of physical illness for the teacher, author, Civil War nurse, and social reformer.

Dorothea Dix was born in rural Maine to alcoholic parents. Her mother was often incapacitated by bouts of depression; her father was physically abusive. At 12 she fled to Boston, where she was raised by her wealthy grandmother and a great aunt. It was there she was exposed to the world of education. Two years later, she was teaching school; by 1819, at age 17, she had established two girls’ schools, one a free evening school for poor children.

But by 1826 Dix had to close her schools due to undiagnosed health problems that recurred throughout her life. For the next three years she focused on regaining her health, spending much of her time reading and writing. With a textbook for children, titled Conversations on Common Things, having been published in 1824, she used this time to publish Meditations for Private Hours (1828), The Garland of Flora (1829) and The Pearl or Affection’s Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Present (1829).

Although not completely well, Dix agreed to accompany a physician friend and his family to the Virgin Islands as their children’s tutor and governess to escape the bitter New England winter. By the time she returned to the classroom in Boston in 1831, her grandmother’s health was failing. For five years, Dix struggled to balance a rigorous teaching schedule while caring for her grandmother, writing at one point to a friend, “There is so much to do, I am broken on a wheel.”

A life change in England

By 1836 it had proven too much. Dix collapsed with an upper respiratory infection that today, with symptoms of difficulty breathing, severe pain and hemorrhage, would likely be diagnosed as tuberculosis. On her doctor’s advice, she again left the classroom, this time going to England to convalesce with friends. While there, she learned about the work of Quakers Elizabeth Fry, prison reformer, and William Tuke, founder of The Retreat, a humane haven for those suffering mental illness. Their work shaped Dix’s drive to investigate and improve conditions and treatment of the mentally ill in America.

Dix returned to Massachusetts in 1841. Her grandmother had just died, leaving an inheritance that gave her the financial independence to devote her time to reform efforts. While teaching Sunday school to female inmates of a Cambridge jail, she asked to inspect the prison, specifically wanting to see its “insane” inmates. She found a group of mentally ill women housed with prostitutes, alcoholics and criminals in dark, dank, unheated, unfurnished, foul-smelling cells with little to no clothing in the most unsanitary conditions.

Massachusetts almshouses and prisons

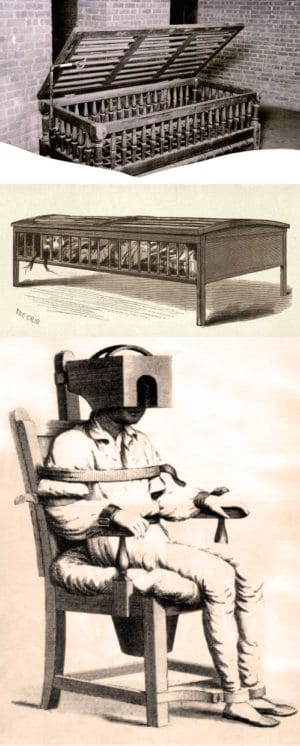

Not knowing what to do with her discovery, she turned to her friends in England for advice. When they suggested she recruit some of the community’s most influential men to her cause, Dix lost no time garnering the support of three of the most highly-esteemed men she knew: Samuel Howe, head of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, abolitionist Charles Sumner and educator Horace Mann. With their help, Dix embarked on an investigation of Massachusetts almshouses and prisons to see and report on the plight of the mentally ill, many of them mistreated, caged and kept in chains.

Seeing the public response to an article Howe published in the Boston Daily Advisor based on her findings, Dix dedicated herself full-time to the cause of the mentally ill. In Providence, Rhode Island, a wealthy businessman donated $40,000 to her cause; it was enough to cover the transfer of that city’s “mentally incompetent” to a new hospital where they would be properly cared for.

New Jersey lunatics

Dix then visited New Jersey and the poorhouse at Lakeland, then part of Gloucester County. The only place for those considered mentally deranged in what eventually became Camden County, its first inmates were admitted in 1803. Those unfortunates were housed in a two-story, wood-framed building called “the mad house.” Dix described it as “populous with imbecile, insane and epileptic patients — 25 to 30 individuals. [It] contains ranges of small cells altogether unfit for the individuals they house.”

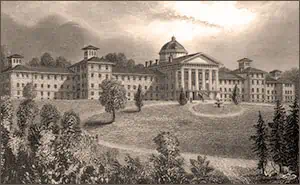

The crude cells ran along a ravine. Each was outfitted with a top and bottom drawer — the top was used to pass food, the bottom to clean out and replace straw for the patients’ beds. Dix presented her findings to the New Jersey State Legislature. Lawmakers approved a new state hospital in 1845, but it would be three years before New Jersey opened its first public psychiatric hospital in 1848. Originally named the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum, we know it as Trenton Psychiatric Hospital.

Congressional testimony

By then, Dix had set her sights on federal reform. Appearing before Congress to report her findings, her pleas for humane, compassionate and medically-informed care were turned down. Nevertheless, she persisted. Her determination was such that Congressmen even set aside a small area in the Capitol library for her research. Finally, by 1854, both the Senate and the House had approved the product of her work — a Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane — only to have it vetoed by President Franklin Pierce on the basis he feared her bill would make the federal government responsible for the “indigent insane” as well as “all the poor of the United States.”

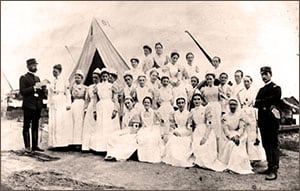

Though her bill was defeated, Dix was not. She traveled the world working on behalf of the mentally ill before returning to America several years before the outbreak of the Civil War, during which she served as superintendent of U.S. Army nurses. Dix trained almost 200 young women for wartime nursing and was honored for her service by Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edward Stanton.

Suffering from the effects of malaria she contracted in 1870 while on a fact-finding tour of southern asylums and hospitals ravaged by the Civil War, Dorothea Lynde Dix retired in 1881. She lived out her life as an invalid in a hospital she had helped established — the New Jersey State Hospital in Trenton, New Jersey where, years earlier, the state legislature had designated a suite of private rooms for her use as long as she lived. She died at age 85 in 1887 and is buried in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Amazing that she lived that long with so many serious health challenges. Now that is one driven woman.