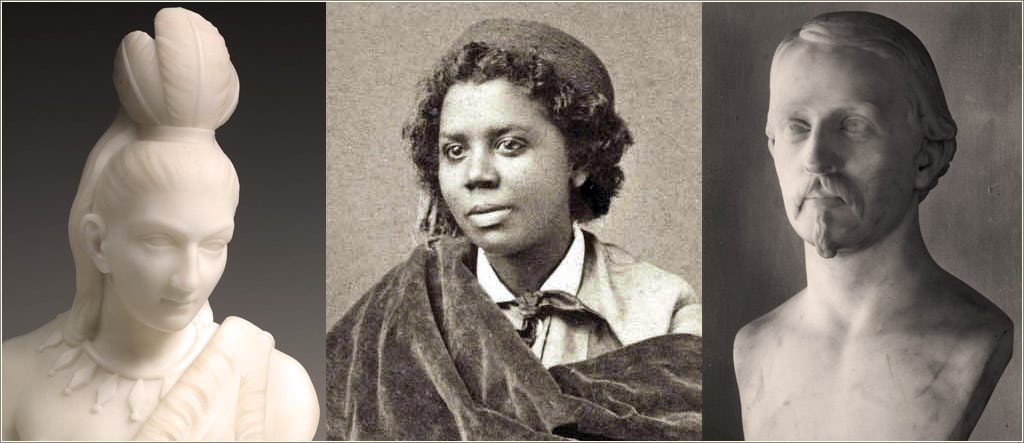

The life story of Edmonia Lewis, a Civil War-era mixed-race orphan who succeeded as an artist only after she expatriated herself to Italy, is a tale of personal triumph in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. And it’s one that makes for a poignant Wednesday’s Woman episode.

In her early life, Lewis was thwarted at every turn as she tried to follow her dream of being a fine art sculptor. As an Ohio college student, she was beaten nearly to death by a white racist mob but later went on to become an acclaimed artist whose masterwork was a sensation at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

Chippewa mother

Standing just over four feet tall, Lewis was born in New York circa 1844 to a free black father and Mississauga (Chippewa band) mother whose names have been lost to history. Orphaned at a very young age, she lived with their mother’s nomadic tribe near Niagara Falls until she was 12 years old. Her brother, Samuel, left the tribe to seek his fortune as part of the California Gold Rush.

Using his riches from the gold fields, Samuel Lewis arranged for his sister’s enrollment at New York Central College in 1856. Founded by abolitionists in 1849, NYCC educated women alongside men, blacks alongside whites, and employed faculty members of both races. Lewis remained at NYCC for three years. In 1859, with her brother’s financial backing and the support of the abolitionist network she cultivated at NYCC, she was admitted to Ohio’s Oberlin College — a coeducational school whose curriculum was rooted in Christian values. She boarded at the home of Rev. John Keep, an Oberlin trustee who championed the rights of women and black students, and who had cast the deciding vote to open Oberlin’s doors to black students in 1835.

But Lewis never graduated. In 1862 she was accused of poisoning two of her white housemates by lacing cups of spiced wine with cantharides, better known as the aphrodisiac “Spanish fly.”

Left for dead

She was tried and acquitted on the grounds of insufficient evidence, but not before being beaten by a white mob and left for dead in an open field. Her remaining time at Oberlin, where the townspeople did not necessarily embrace the progressive views of Rev. Keep, was one of isolation and prejudice. A year after the trial, Lewis was falsely accused of stealing art supplies — charges that were, again, dropped due to lack of evidence. Though acquitted, her reputation at Oberlin was in tatters and she was expelled.

In early 1864 Lewis moved to Boston, determined to become an artist. Supported by the abolitionist network, and armed with a letter of introduction from Rev. Keep, she met William Lloyd Garrison; he introduced her to sculptor Edward Brackett, who took Lewis under his wing.

Portrait busts of abolitionists

Her first works were portrait busts of prominent abolitionists — Garrison, Charles Sumner and Wendell Phillips. But it would be her busts of abolitionist John Brown and Boston’s hero and leader of the Civil War’s celebrated 54th Regiment of African American soldiers, Col. Robert Gould Shaw, that financed her trip to Europe in 1865.

Edmonia Lewis settled in Rome, learned Italian, and, as part of its community of expatriate sculptors, rented a studio. Rome provided an abundance of fine white marble along with a number of local carvers whose skill transformed sculptors’ plaster models into finished works of art. It was in that respect that Lewis was unique — she taught herself how to carve marble and completed most of her pieces without assistance.

In the 1870s Lewis returned to the United States to exhibit and sell her work, traveling cross-country as one of the first sculptors to exhibit in California. But the pinnacle of her career was at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 with the exhibit of Death of Cleopatra, a life-sized sculpture of Cleopatra in the throes of death. Lewis was the only artist of color invited to exhibit. The piece attracted visitors at the same time it repulsed them. One critic wrote, “The effects of death … are absolutely repellant … and could only have been produced by a sculptor of genuine endowments.”

Fading star

By the 1880s, Lewis’ star had faded. Her neoclassical style was no longer in demand, bronze had eclipsed fine Italian marble as the favorite medium of the day, and the eyes of the art world had turned to Paris.

Few details of Edmonia Lewis’ later life were known until retired professor and Lewis scholar Marilyn Richardson began digging into the trove of newly-digitized records from around the world in the 1980s. Poring over census sheets, burial records and wills, Richardson learned Lewis had moved from Rome to London. It was there, in Hammersmith Infirmary, that she died of kidney disease. Having asked in her will to be buried in a dark walnut coffin, Edmonia Lewis’s remains rest in grave #C350 of St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in London, her gravesite is marked with a lichen-covered granite slab devoid of even the most simple carving — her name.

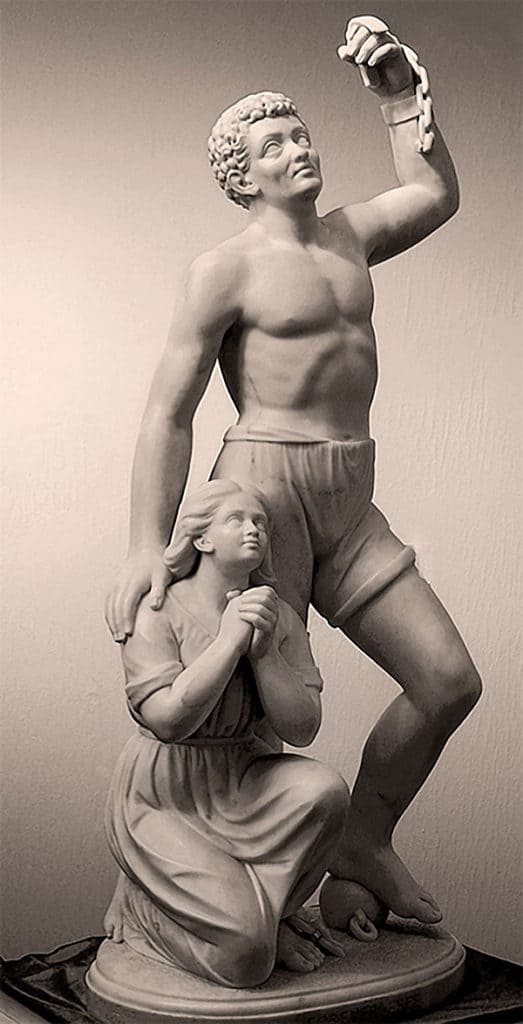

Her celebrated work, Death of Cleopatra, once assumed lost, can be seen at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. An 1867 piece commemorating the ratification of the 13th amendment abolishing slavery in the United States, Forever Free, is displayed in Howard University’s Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

You can read a free sample chapter of our Edmonia Lewis biography at http://edmonialewis.com

Thanks to historian Bobby Reno [@Moonmisty49] and GoFundMe, Edmonia Lewis’s grave received a beautiful marker in late 2017. https://www.gofundme.com/restore-edmonia-lewis-grave?viewupdates=1&rcid=r01-14993040042-ea96c32566f844a0&utm_source=internal&utm_medium=email&utm_content=cta_button&utm_campaign=upd_n