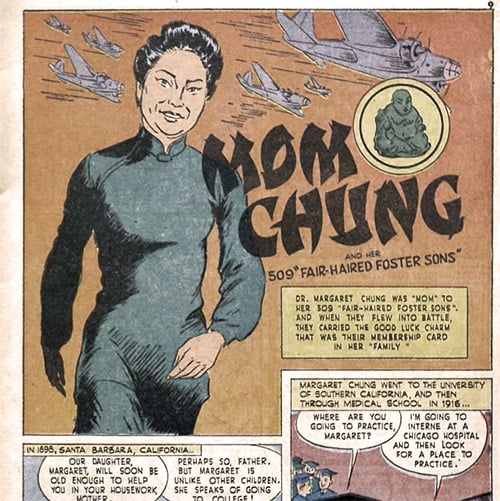

From the time she was 10 years old, Margaret Chung wanted to become a doctor. But with no dolls or toys to practice on, she resorted to using banana peels to practice her suture technique. Born into a time when the stories of Chinese Americans were those of rejection and exclusion, Margaret Chung learned early on she would need to forge a distinctive path for herself if she were to achieve her dreams.

The eldest of 11 children, she was born in California in 1889 to parents who immigrated from China as children. Chung always knew she wanted to become a medical missionary to China. In 1911, she won a Los Angeles Times scholarship to the University of California’s College of Physicians and Surgeons by selling newspaper subscriptions, then worked her way through school as a waitress, a salesperson for surgical instruments, and by winning cash prizes in several speech contests.

Academic misogyny

She was the only woman and non-white student in her med school class. As the outsider, she adopted strategies — dressing in masculine clothing and going by the name Mike — to get by. And at a time when some Chinese parents still sold daughters into domestic service or prostitution, Chung went on to graduate in 1916, becoming the first Chinese-American female physician in the United States.

Her applications for medical internships were rejected, and she was denied a position as a missionary, because of her race. But Chung never gave up on becoming a healer. Searching for both a professional and personal sense of belonging, she worked as a scrub nurse in Los Angeles’ Santa Fe Railroad Hospital. After a few months, she left for Chicago and an internship at the Mary Thompson Women’s and Children’s Hospital, then served her residency in psychiatry at the Kankakee State Hospital for the Insane; she was eventually appointed Illinois’ state criminologist.

But when her father died in 1918, she returned to Los Angeles and the Santa Fe Railroad Hospital, where she accepted a position as a surgeon, specializing in performing delicate plastic surgery on patients who experienced serious industrial accidents. She also started a private practice, where actress Mary Pickford became one of her first celebrity clients. Being in Southern California just as Hollywood and America’s film industry took off, Dr. Margaret Chung became known as the physician to the stars.

San Francisco Chinatown

In 1923, Chung visited San Francisco, fell in love with the city, and moved there to open one of the first Western medicine clinics in Chinatown, with a special focus on helping Chinese women. She was the first American doctor in the neighborhood and the first woman to practice modern medicine there. On top of that, she was a single woman who favored masculine clothing. Between their skepticism of Western medicine and their suspicions about her sexuality, many Chinatown residents treated Chung as an outsider.

So she found success treating non-Chinese patients, her “outsider” status actually working to her advantage. As with other Chinese Americans during this period, Chung deliberately cultivated an “Oriental” image that appealed to white visitors seeking exotic Chinese medical treatments.

But other patients sought her out specifically because they thought she was a lesbian. And while Chung never embraced that label, she did have several romantic, intimate relationships with women — including Sophie Tucker, one of America’s most popular entertainers in the first half of the 20th century.

Gathering clouds of war

In the 1930s, Margaret Chung’s life changed with Japan’s invasion of China that eventually led to the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and sparked a new American sympathy for the Chinese. It was in this environment that a US Navy Reservist named Steven Bancroft reached out to Dr. Chung in 1931, hoping she could help him get a commission in the Chinese military. Why he chose Chung is unclear; he may have known her simply by her reputation with white patients. Whatever the reason, Chung had to tell him she had absolutely no influence whatsoever with the Chinese military.

But she was impressed with his sincerity and political fervor, and invited him (and his six housemates, all unemployed flyers) to dine with her. They hit if off immediately, dining together most nights, and even going camping and hunting together. It was an unlikely group — a 42-year-old Chinese American female physician and seven white airmen, recent graduates of UC-Berkeley and former college football players. But it worked.

Fair-haired bastards

So much so, one of the pilots laughingly remarked, “Gee, you’re as understanding as a mother, and we’re going to adopt you; but, hell, you’re an old maid and haven’t got a father for us.” As Chung recalled in her autobiography, “feeling facetious, I cracked right back at them, ‘Well, that makes you a lot of fair-haired bastards, doesn’t it?'” The name stuck. As the original seven Fair-Haired Bastards traveled the globe, they recruited others until, by the start of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, “Mom” Chung’s adopted children numbered well over 500.

Chung volunteered her own services as a front-line surgeon to the Chinese government at least twice, but was turned down because she was an American. Instead, she was asked to secretly recruit pilots for a unit that became known as the famous “Flying Tigers,” squadrons of American pilots from the Marines, Air Corps and Navy who flew under Chinese colors.

Allied war effort

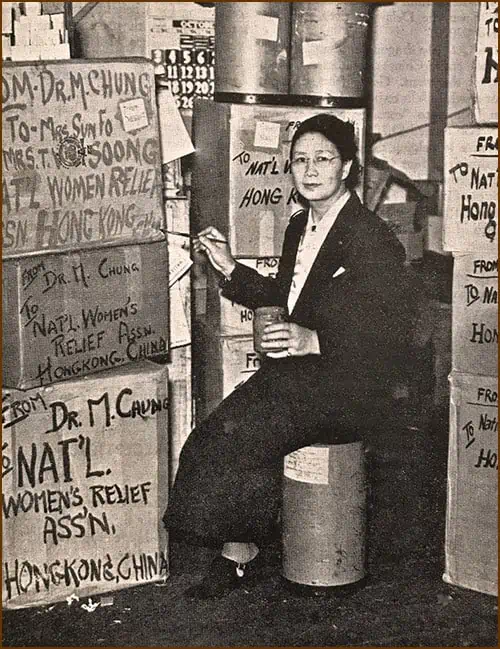

In 1941, once America entered World War II, Chung used her influence and patriotic spirit to work for the Allied war effort, supporting her “sons” at the front with letters and Christmas gifts, and keeping them connected to one another. Her fame grew as her adopted family was hailed by the media as an example of American patriotism.

By the end of the war, Chung’s adopted family numbered more than 1,500. And while most of Chung’s “children” were American servicemen, she also “adopted” Hollywood stars like Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, Helen Hayes and Tallulah Bankhead, along with politicians and top military brass like Fleet Admirals Chester W. Nimitz and William “Bull” Halsey Jr.

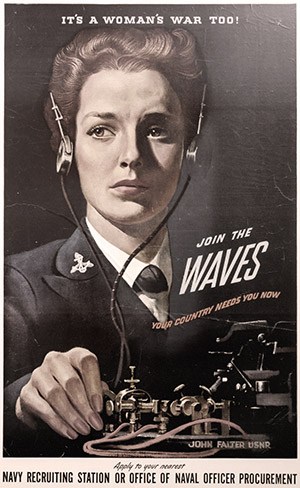

Chung also advocated for women’s rights, using her fame to push for greater inclusion of women in the U.S. Military and lobbying for legislation to create the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service).

Helped to create U.S. Navy’s WAVES

She wasn’t shy when it came to drawing on her connections to government officials and her vast network of “adopted” children to work behind the scenes. And though the WAVES were established in 1942, Margaret Chung never got the proper credit for her role in its creation. In fact, her own repeated applications to join the corps were rejected out of hand because of her race, her age and lingering rumors about her sexuality.

It was during this time, when she became known as a wartime celebrity, Chung began to dress in a more feminine way. Early photos capture her in dark, masculine suits, her hair slicked back, wearing no-nonsense glasses. But in some of her favorite photos taken later in life, she’s dressed to the nines in ermine and furs, with carefully styled hair and makeup. While her gender identity seems to have shifted, at least for the public, the fact that an FBI report on her during the 1940s cited rumors she was a lesbian may have had something to do with it.

On August 14, 1945, “Mom” Chung learned of Japan’s surrender over the radio. Having dedicated 14 years of her life to the war cause, she thought it only fitting that one of her adopted sons, William Sterling Parsons, had served as the bomb commander on the Enola Gay.

Dr. Margaret Chung retired from practice within 10 years after World War II. She died of cancer in January of 1959 at the age of 70. Her funeral, which she herself planned, was attended by hundreds, with pallbearers that included Admiral Chester Nimitz, conductor Andre Kostelanetz and San Francisco Mayor George Christopher.

A larger-than-life personality to the end, her front-page obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle described her as “‘Mom’ to thousands of World War II veterans and show business celebrities; an inveterate theater district ‘first-nighter’; and a charming figure in white ermine who frequently carried a parakeet in a cage that dangled from her wrist.”

To this day, few civilian patriots have ever gained the level of celebrity and influence accorded to Dr. Margaret Chung. Throughout her life, she battled racism, sexism and homophobia, challenged social morés and broke professional barriers. She is considered the inspiration for the character Dr. Mary Ling in the 1939 film King of Chinatown, portrayed by actress Anna May Wong. Her “adopted” sons named at least three Flying Fortresses in her honor during World War II, and her support for China during the war was memorialized in a comic book. And to honor her early service to Los Angeles’ Santa Fe Railroad Hospital, a tunnel boring machine for the San Francisco Municipal Railway’s Central Subway was even named “Mom Chung” in 2013.

Her papers are housed at the Ethnic Studies Library at the University of California, Berkeley. A biography of her life by Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, Doctor Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards, was published in 2005 by the University of California Press.

And today, if you visit Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood, be sure to look for Margaret Chung’s bronze biographical marker, part of The Legacy Project’s Legacy Walk — the world’s only outdoor LGBTQ museum, celebrating and affirming the lives of LGBTQ people and honoring their contributions to world history and culture.

This is the best article I’ve come across on the truly remarkable life of Dr. Margaret Chung, and one that my father would have delighted in reading. He was proud to be one of Mom Chung’s “bastards”, or as is imprinted on the inside of the wallet he received from this magical woman, “Bill Baldwin – My Beloved Son, Kiwi 234”.

What began with pilots, soon needed additional categories, Dolphin for the Navy “sons” and Kiwi, the non-flying bird for people like my dad (ulcers made him 4F), who was Special Events Director for the Blue Network at KGO radio in San Francisco.

Whenever he spoke about his time with Mom Chung, the respect and admiration he had for her was obvious.

The whimsy you noted was evident in her standing “rule” governing the countless dinners she hosted at her home for Army and Navy men , ” the highest ranking person does the dishes”. At a time when the continuing existence of the country was very much in doubt, it was her determination in the face of truly staggering odds for her personally which endeared her to so many.

Best regards,

Bill Baldwin, Jr.

Los Angeles