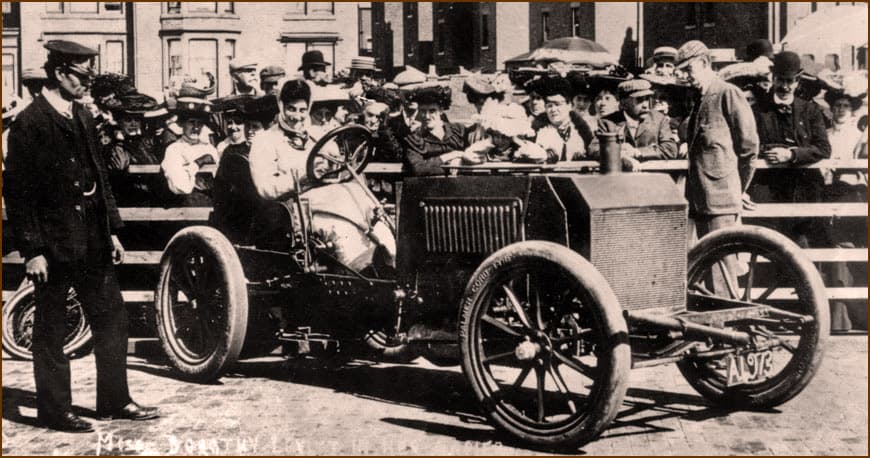

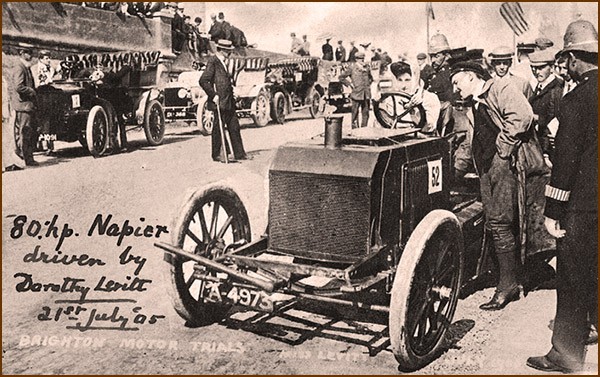

If you saw the 1986 movie Top Gun, you’ll remember the tag line: “I feel the need … the need for speed.” But 81 years before Maverick and Goose uttered those words, Dorothy Levitt, self-styled “motoriste,” became the first English woman to compete in automobile racing, setting the Ladies World Land speed record and earning the nickname The Fastest Girl on Earth, driving an 80-horsepower Napier at the lightning speed of 79.75 miles an hour.

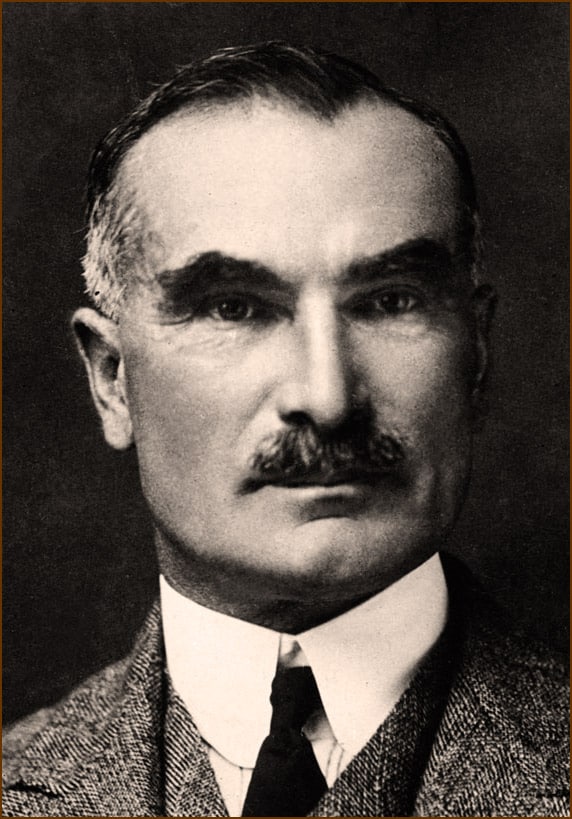

As important as this Edwardian Age trailblazer was, very little is known about her early life. She was born Dorothy Elizabeth Levi in 1882 or 1883 in Hackney, an East End borough of London. Her father was a Jewish tea dealer and jeweler who Anglicized the family’s original surname to Levitt in 1901. Her mother is said to have been the daughter of a retired hotelier and diamond merchant.

Advocate for women drivers

A journalist and author, Dorothy Levitt had a knack for self promotion, and was never one to let a few ho-hum facts stand in the way of a ripping good story. She was fiercely independent and a tireless advocate for women drivers. She lived alone or with friends and never married, preferring the company of her ever-present little Pomeranian dog, Dodo.

Levitt’s first exposure to the world of auto racing came when she was hired as a secretary by auto manufacturer D. Napier & Son Limited at the dawn of the British auto industry when motoring was clearly a man’s province. Edwardian women who were interested, much less involved, in any of the mechanical disciplines were seen as masculine in outlook, temperament and style. And Dorothy Levitt was anything but masculine. In fact, Jean Bouzanquet, in his 2009 Fast Ladies: Female Racing Drivers 1888 to 1970, described her as a “beautiful secretary with long legs and eyes like pools.”

But when you worked for one of Britain’s first motor racing companies, you were bound to come into contact with that most dashing and rakish of creatures: the manly race car driver. Specifically, one Selwyn Edge — an Australian driver who sat on Board of Directors of D. Napier & Son Limited.

Savvy promoter

While racing a Napier in 1902, his focus was captured by another driver — a French woman named Camille du Gast, one of the first women to obtain a driver’s license, and only the second to drive in an international motor race. Always a savvy promoter, and knowing a good PR angle when he saw one, he was quick to realize the value of having a good-looking female race car driver behind the wheel of a fast car. Lucky for him, he found her sitting at her desk, behind a typewriter. Edge soon promoted Levitt to become his personal assistant, launching her driving career, arranging for training in Paris, and providing her with cars to promote his dealerships. And, naturally, as in every good story, she was also presumed to be romantically involved with Edge at the time.

At a time when there were few opportunities in England for men to race fast cars, the idea of a female driver was simply unheard of. Dorothy Levitt’s first experience behind the wheel seems to have come from a young Napier salesman who was insulted by having to teach a woman to drive.

Apprenticed to French auto maker

Edge then arranged a six-month apprenticeship at a French auto maker that involved not just driving, but chauffering and engineering. After all, a driver in 1903 had to do more than simply work the pedals and handle the wheel; when motoring meant dealing with routine breakdowns and sputtering engines, they needed to know how things actually worked.

Returning to England after completing her apprenticeship, Levitt began teaching well-heeled American tourists and members of the British aristocracy how to drive, and gave public lectures encouraging British women to get behind the wheel.

Levitt became the first English female driver to compete in an automobile race in 1903. And while she didn’t place among the top prize winners, she wrote in her diary that she was determined to do better. At a time when motor cars were only within the reach of the wealthy and upper-class, and women were expected to be content staying home, raising children and tending to their husbands’ needs, British society was astonished to see a woman working as a secretary compete in a sport long held to be male-only territory.

First water speed record

Napier also made marine engines. And in a 1903 British International event, Levitt took the helm of a 40-foot steel-hulled speedboat, handily won the event, and set the world’s first water speed event — 19.3 miles per hour. But it was 1903. So, naturally, since the boat was owned and entered by Selwyn Edge, the trophy she won that day was inscribed to “S. F. Edge.”

Two years later, Dorothy Levitt made good on her promise to do better, recording every speed trial, every race and every sweepstakes in her diary. “February 1905: Did Liverpool and back to London in two days, averaging 20 miles per hour for the entire 411 miles. Unaccompanied by mechanic. Drove an 8-horsepower De Dion. May 1905: Won Nonstop Certificate at Scottish Trials. Ran over very rough and hilly roads in the Highlands in an 8-horsepower De Dion. July 1905: Won Brighton Sweepstakes in an 80-horsepower Napier at the rate of 79.75 miles per hour, constituting the woman’s world record. Beat a great many professional drivers. Drove at rate of 77.75 miles in Daily Mail Cup.”

Levitt broke her own record in 1906 in a 90-horsepower, six-cylinder Napier racing car, driving at 91 miles an hour. Her diary reflects a “near escape as front part of bonnet (hood) worked loose and, had I not pulled up in time, might have blown back and beheaded me.”

1,000 mile race

Over the next several years, she participated in speed trials, hill climbs and endurance events, including a 1,000-mile race she completed in five days without a mechanic. She was only prevented from winning when a valve came loose on the last day of the race. She fixed it herself, but it took more than the 20 minutes allotted, causing her to be disqualified.

She usually drove without a mechanic or official observer, accompanied only by her tiny dog named Dodo at a time when there were no road maps, reliable road signs or gas stations, getting her petrol from hardware stores and chemists (pharmacies) along the way. England’s posh racing circuit took notice, christening her the “Champion Lady Motorist of the World” while the British press delighted in dubbing her the “Fastest Girl on Earth.”

But she also caught the attention of American newspapers big and small, from coast to coast, who covered her daring exploits behind the wheel as the last paragraph of this piece from the Logan, Ohio, Democrat-Sentinel reported on January 3, 1907: “Miss Levitt has developed an unusual commercial talent with the automobile business, her income being $10,000 a year. She has challenged any woman automobilist in America to race with her.”

Trout fishing and poker

When she wasn’t behind the wheel, Levitt filled her time writing, hunting and socializing. In a 1906 interview with London’s Penny Illustrated Paper, she explained how she balanced “the fearful excitement of automobile racing” by going trout fishing. She was always up for a good game of poker, and touted her expertise at roulette before teasing reporters with tidbits about her “most wonderful secret system by which she is going to attempt to break the bank at Monte Carlo.” Her atypical approach to life — an independent young woman living with friends in London’s West End, waited on by servants — made her the Edwardian Age’s equivalent of the “it girl.”

Capitalizing on her reputation as a trailblazer for a woman’s “right to motor,” Levitt wrote and published The Woman and the Car: A Chatty Little Handbook for Women Who Motor or Want to Motor in 1909, drawing from her columns for The Graphic, a British weekly illustrated paper. She dispelled myths and countered clichés about women drivers — they weren’t strong enough to take the wheel, were hopelessly ignorant about mechanics, and couldn’t possibly retain their femininity while learning the ins and outs of an engine.

It was filled with practical advice, including one suggestion that would one day become standard equipment for every automobile on today’s roads. She suggested every woman “carry a little hand-mirror in a convenient place when driving” and “hold the mirror aloft from time to time to see behind while driving in traffic.” Her Chatty Little Handbook became extremely popular as women followed her lead, including close friend and English romance novelist Dame Barbara Cartland.

What to wear while motoring

A skilled horsewoman, she compared the breathless exhilaration of motoring to steeplechase racing. But she was all business when it came to explaining everything from what women should consider when choosing a car to the costs and accessories involved, the details of an engine, how to make repairs, and that all-important topic for female drivers — what to wear while motoring.

An Edwardian woman who was interested, much less actively involved, in a male-dominated sport like race car driving was considered masculine in personality, temperament and style, since she often had to resort to wearing male clothing when behind the wheel. But Levitt, who loved fashion, turned that old trope upside down, dressing in flattering feminine clothing complete with matching hats and veils, and loose, lightweight coats she designed that came to be known as dusters.

Mechanical tips

She preferred shoes over boots, “as they give greater freedom to the ankles and do not impede circulation as a tightly-laced or buttoned boot would do.” Plain “tailor-made” frocks were the order of the day, giving the motorist the advantage of still “appearing trim and neat” after a day’s run. Lace and “fluffy adjuncts” were frowned upon. A no-nonsense linen overall — a long-sleeved garment that slipped on and fastened at the back, was indispensable for working on the engine, as was a small cake of Antioyl soap; while, in a pinch, gasoline would remove grease, Levitt warned that “petrol roughens the skin,” while the Antioyl did not.

She also let readers in on the “secret of the dainty motoriste”: a little drawer located under the car’s seat. She advised using it to store “a pair of clean gloves, extra handkerchief, clean veil, powder puff, hair pins and a hand mirror” before adding, “Some chocolates are very soothing sometimes!”

But the one accessory Levitt was never without, even while racing, was little Dodo, rumored to have bitten at least one official observer during a speed trial. When male competitors ridiculed her by showing up at races with stuffed and porcelain dogs tied to their cars, she paid them no mind, instead offering them dog biscuits at posh receptions staged after each even

Death by “misadventure”

Just as Dorothy Levitt had once balanced the “fearful excitement of automobile racing” with quieter pastimes, her meteoric rise to fame was balanced by an equally abrupt disappearance from racing and all public engagements sometime around 1910. Much of her life after that point remains undocumented until 1922, when she was found dead in her bed in her Marylebone apartment on Baker Street. She was 40 years old. The cause of death was “morphine poisoning while suffering from heart disease and an attack of measles.” The inquest that followed recorded a verdict of “misadventure.”