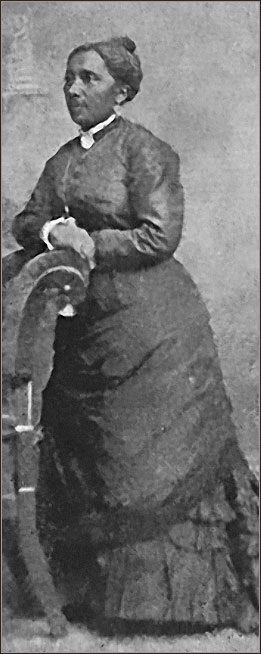

A century before civil rights icon Rosa Parks kept her seat at the front of an Alabama bus, a 24-year-old African American woman was forced off a New York City streetcar and jeeringly told to seek redress if she could. She could, and she did, ultimately desegregating New York City’s public transportation system. She is this Wednesday’s Woman, Elizabeth Jennings.

A third-generation New Yorker, Jennings was raised in a solid middle-class African American community. Her grandfather was a slave-turned-soldier in the American Revolution. Her father was a successful entrepreneur who used the profits from his business to generously support abolitionist causes in the Northeast.

While slavery was officially outlawed in New York in 1827, segregation was not. African Americans were routinely excluded from theaters, concert halls and hotels; many churches, schools and workplaces were off-limits; black children were not accepted in the city’s orphanages. Public transportation was also segregated.

“Colored only” cars

Horse-drawn city streetcars were privately owned and operated, and conductors decided who rode and who did not. Blacks were relegated to specially-marked cars that ran infrequently, if at all.

But on July 16, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings and a friend were on their way to the First Colored Congregational Church, where Jennings was the organist. Running late, they jumped aboard a white-only car rather than wait for the “colored” car that might never come. The conductor tried to get Jennings off, first alleging the car was full. When that proved false, he claimed other passengers wanted her off.

Street fight

Jennings stood her ground in what became an ugly street fight. The conductor laid hands on her, trying to force her off the car. Still she resisted, first holding firm to the car’s window frame, then grabbing onto the conductor’s jacket. He eventually pushed her down onto the car’s platform. But it would take the help of a police officer to finally eject Jennings from the car, sore and injured, her clothes soiled, her bonnet ruined.

[perfectpullquote align =”right” color=”#663300″ size=”20″]”thrust me out, and then pushed me down, and tauntingly told me to get redress if I could.”[/perfectpullquote]Outraged by such disrespectful, disgraceful treatment, Jennings wrote about her experience in a letter published by abolitionist Horace Greeley in his New York Tribune. Jennings described how the two men “thrust me out, and then pushed me down, and tauntingly told me to get redress if I could.” Her story was picked up and publicized by Frederick Douglass in his newspaper, where it garnered the nation’s attention.

Future U.S. President

The next day, her church and community gathered to protest the incident. Jennings sued the Third Avenue Railway Company, its driver, and the conductor for $500. Her case was handled by 24-year-old Chester A. Arthur, who would be elected president of the United States in 1881. Jennings won her case, the judge ruling, “colored persons, if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the company, nor by force or violence.” The jury awarded her $250 in damages, less than half what she had requested. But money proved to be the least important aspect of her case.

Elizabeth Jennings’ case became the precedent cited in all future suits against discrimination on public transportation and her family established an organization to advocate for the desegregation of the city’s pubic services. By 1859, almost 100 years before Rosa Parks’ bus ride, almost every streetcar in New York City had been desegregated.

Jennings went on to lead a quiet life. She married Charles Graham of New Jersey in 1860 and they had one child, a son, who suffered poor health and died at just a year old of “convulsions” in 1863. Her husband passed just a few years later. Elizabeth Jennings died in 1901 and was laid to rest alongside her husband and child in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hill Cemetery. But her legacy lives on.

New York Transit Museum

The New York Transit Museum in Downtown Brooklyn tells the story of Elizabeth Jennings Graham in an exhibit titled “On the Streets.” And in 2007 the third- and fourth-grade students of P.S. 361 on Manhattan’s Lower East Side succeeded in having a street named for her. The intersection of Spruce Street and Park Row in the Financial District neighborhood of New York City, a busy New York City Transit stop, now bears a permanent sign marking “Elizabeth Jennings Place.”