Happy Valentine’s Day! We’ve all been there. You stare at racks of valentines, reading and replacing card after card. This one’s too schmaltzy; that one’s not romantic enough. Just go with cute and funny? If you suffer valentine anxiety, blame today’s Wednesday’s Woman: Esther Howland, “Mother of the American Valentine.

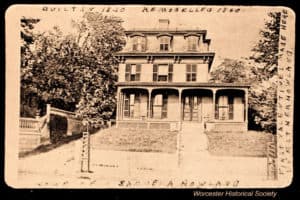

Howland was born into a well-to-do Worcester, Massachusetts, family who owned the largest book and stationery store in town. She graduated from Mt. Holyoke Female Seminary in 1847, where she took part in the traditional Valentine’s Day fun of exchanging letters and notes with classmates.

Consumer savvy

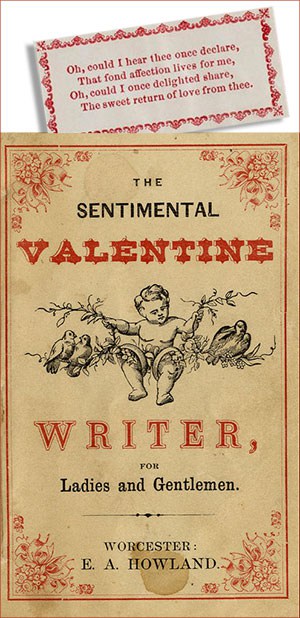

At age 19, she got her first glimpse of frilly, imported European valentines in her father’s store. It was a time when American valentines might be as simple as cut paper hearts on which the sender penned a sentimental verse, or, worse, what came to be known as “vinegar valentines” — insulting missives, often sent anonymously. Stationers in New York City produced lithographed valentines for the mass market, but they couldn’t hold a candle to their imported cousins. But those cards were unaffordable for most Americans. Howland, recognizing an opportunity when she saw one, set her mind to create romantic, elaborate cards with a lower price tag for the American market.

She persuaded her father to order high-quality stationery supplies from New York and England from which she made a dozen sample cards. She then talked her brother, a salesman for their father’s company, into taking the cards to show on his next business trip, hoping to generate a few hundred dollars in orders. When he returned with over $5,000 (2017 equivalent = $130,000) worth of orders for her fancy valentines, Howland knew she had herself a business.

Her first employees were local women, working from a guest bedroom in Howland’s home on Summer Street. She personally designed each card, hand-cutting individual elements for her employees to copy. Each woman had a task, from cutting paper to trimming cherubs, stenciling, cutting lace, printing verses or adding gilt embellishments. As each completed her task, she passed the card to the next worker in true assembly-line fashion. Howland also reached out to and hired women who preferred to work from home.

Kitchen table piece work

Every week each woman received a box carefully packed with all the supplies she needed; a week later the finished cards were picked up for Howland’s personal inspection. According to an 1858 article in Harper’s Weekly, her employees were paid from $3 to $8/week, year round.

With meticulous attention to detail, Howland transformed simple valentine cards into works of art, embellishing them with silk, satin, bits of embroidery, gilt, ribbons and paper flowers. She also introduced inside envelopes to hold secret messages, love poems, locks of hair or the occasional engagement ring, and pioneered the use of flaps, folds and springs that were the forerunners of today’s pop-up cards.

Howland’s business eventually outgrew her family’s guest bedroom. She incorporated her business as the New England Valentine Company and, in 1879, rented a building on Worcester’s main street. With her work in demand and valentine cards shipping from coast to coast, revenues reportedly topped $100,000 annually — the 2017 equivalent of $2.6 million.

But in 1880 Howland sold her business to devote herself to caring for her father, who had become ill.

Esther Howland, proclaimed “Mother of the American Valentine” after her death in 1904, had never married. She died after being bedridden for eight months, then confined to a wheelchair, as the result of a fractured femur which, in those days, was a debilitating injury. She is buried in Mount Wollaston Cemetery in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Today Esther Howland valentines are prized by collectors. In pristine condition, just one card can sell for between $300 to $400. And, since 2001, she is honored every year when the Greeting Card Association bestows its annual Esther Howland Award for a Greeting Card Visionary. Ironically, some of Howland’s original valentines are archived at Mount Holyoke College, even though the school’s founder eventually banned students from sending “those foolish notes called valentines.”

A verse from a Howland valentine circa mid-1800s:

Anticipation.

How oft my bright and radiant eyes

O’erflow with love – and so do thine

How bright the morrow’s sun would rise

Would’st thou, love, be my Valentine.