Pauli Murray. Fannie Lou Hamer. Dorothy Height. Rosa Parks. Mary Church Terrell. Ida B. Wells-Barnett. When you think of female civil rights activists, these are just some of the names that come to mind. But Elizabeth Peratrovich? Chances are her name probably wouldn’t be on that list. But she was the Alaska Native civil rights champion who was instrumental in the 1945 passage of what was the United States’ very first anti-discrimination law.

Elizabeth Peratrovich, a proud member of the Tlingit Nation, was born in Petersburg, Alaska, population 585 in 1910. The daughter of an indigenous woman and her mother’s Irish brother-in-law, her biological parents left her in the care of the Salvation Army. Not long after, she was adopted by Andrew Wanamaker, a minister and charter member of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, and his wife, Jean, who was a basket weaver. The mission of the A.N.B., a nonprofit founded in 1912, was to promote Native solidarity, achieve U.S. citizenship, abolish racial prejudice, and secure economic equality through recognition of Native land titles and mineral rights.

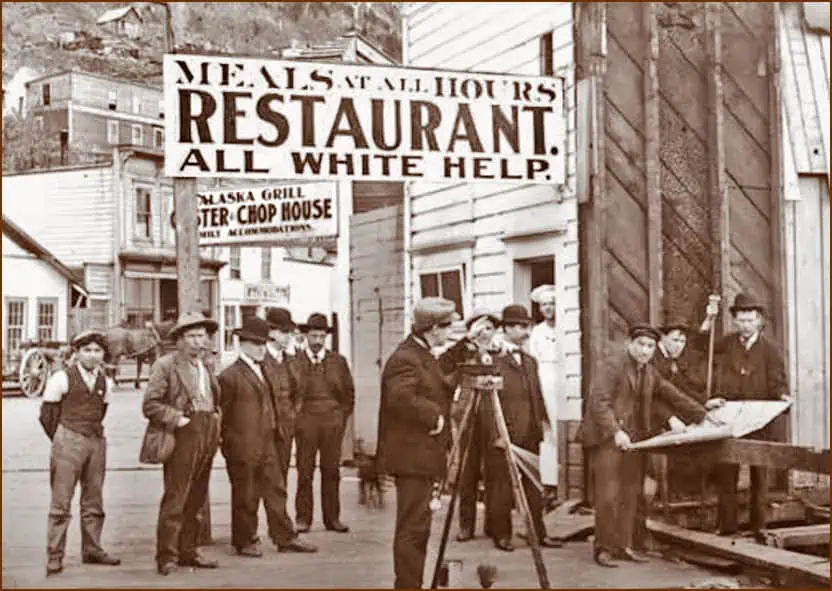

Alaska’s Jim Crow-Like Laws

Living in poverty with her parents in the coastal city of Sitka, Elizabeth Wanamaker grew up speaking English and Tlingit. Not unlike African Americans in the lower 48, Indigenous families like hers experienced daily discrimination by the Territory’s white residents as reflected in the all-too-familiar signs of that era: “No Natives Allowed,” “No Dogs, No Natives,” “We cater to white trade only.” Like Black people, Indigenous people were restricted when it came to where they could live, which hospitals would treat them, which restaurants would serve them, and which theaters they could enter.

Wanamaker was 10 when her family moved to the Native village of Klawock on Prince of Wales Island, where she first met the young man who would become her husband. Roy Peratrovich, son of a Croatian fisherman and Native Tlingit woman, worked as a fisherman, boat captain and trapper in his hometown of Klawock, later serving as its mayor. Wanamaker, meanwhile, dreamed of becoming a teacher. After graduating from the Western College of Education in Bellingham, Washington — now part of Western Washington University, she returned to Klawock, where she and Peratrovich married in 1933. Eight years later, in 1941, they relocated to the city of Juneau, capital of what was then the Alaska Territory.

Looking for a house to rent in the city, they were turned away from several prospects because they were Indigenous. They were also told their children were not allowed to attend school with white children and would be required to attend a separate school for minorities. Elizabeth Peratrovich wasn’t having it. She met with the school district superintendent, who agreed to admit her children. No one knows exactly what she said, but her family believes she reminded him that she and her husband paid school taxes just like every other family. And so it was that Roy Peratrovich, Jr., became the first Alaska Native child to attend the school intended for white children in Juneau, whose public schools wouldn’t be fully integrated until 1947.

Alaskan Native Brother and Sisterhood

Roy Peratrovich Sr. soon became leader of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. Much later in his life, he joined the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, heading up their Anchorage office. Elizabeth Peratrovich was elected Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood in 1944. Together, they fought for and established the civil rights framework for generations of Alaskans when it came to the right to vote, access to public accommodations, public education, and equal employment opportunity.

Not long after America entered World War II, the couple spotted a “No Natives Allowed” sign on the door of the popular Douglas Inn, just across the channel from Juneau. Despite having grown up with Alaska’s version of America’s racist Jim Crow Laws, that sign was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It spurred them to write a letter to Alaska’s governor, Ernest Gruening, stating, “The proprietor of the Douglas Inn does not seem to realize that our Native boys are just as willing as the white boys to lay down their lives to protect the freedom he enjoys.” Calling the sign “an outrage,” they reminded the governor, “we will still be here to guard our beloved country while hordes of uninterested whites will be fleeing South.”

Much to his credit, Gruening sided with the Peratroviches, joining them in their push to usher an anti-discrimination bill through Alaska’s Territorial Legislature in 1943; it failed in a tie vote of 8-8 in the House.

Disappointed, but not dejected, Elizabeth Peratrovich doubled down on her efforts, traveling throughout Alaska urging Indigenous people not just to join the cause, but to actively campaign for seats in the legislature. Two years later, a new bill was slated to reach the Senate floor in 1945; Congress had increased the size of the Territory’s legislature; two Indigenous people had been seated; and the House had already approved the bill. Despite the odds against its passage, it set off hours of debate, drawing so many onlookers to the gallery the crowd spilled out the doors of the Capitol.

“Barely Out of Savagery”

Finally, one very vocal opponent, Senator Allen Shattuck from Juneau, went on record with his comments: “Far from being brought closer together, which will result from this bill, the races should be kept further apart. Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?”

Now, Elizabeth Peratrovich was no stranger to the often-tedious business of government. In fact, she always brought her knitting to pass the time during legislative sessions. But this was enough to make her put down her knitting needles. The floor had been open for public comment for a while when Peratrovich rose to be acknowledged. She was last to speak. And once she was sure she had everyone’s attention, speak she did: “I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind gentlemen with five thousand years of recorded civilization behind them of our Bill of Rights.”

She went on to describe the restrictions and injustices her family and other Natives faced daily, including their inability to get decent housing. Unfortunately, it seems Senator Shattuck never heard that old saying, “when you’re in a hole, stop digging.” He asked Peratrovich if she thought the bill would end discrimination. She replied, “Do your laws against larceny and even murder prevent those crimes? No law will eliminate crimes, but at least you as legislators can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak your intent to help us overcome discrimination.”

Senate Floor Victory

With that, the galleries and Senate floor erupted in a “wild burst of applause,” as Gruening would write in his 1973 autobiography, Many Battles. The 1945 Anti-Discrimination Act passed in a vote of 11-5 and was signed into law by Governor Gruening. It read, “All citizens shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of public inns, restaurants, eating houses, hotels, soda fountains, soft drink parlors, taverns, roadhouses, barber shops, beauty parlors, bathrooms, resthouses, theaters, skating rinks, cafes, ice cream parlors, transportation companies, and all other conveyances and amusements.”

Violators faced imprisonment for up to 30 days or a $250 fine. It also banned discriminatory signage based on race. But Ernest Gruening went a step further, going on record to make it very clear that the 1945 Anti-Discrimination bill would have never passed without the efforts of Elizabeth Peratrovich.

The next morning, in a story on page eight under the headline “Super Race Theory Hit in Hearing,” The Daily Alaska Empire wrote, “Opposition that had appeared to speak with a strong voice was forced to a defensive whisper at the close of yesterday’s Senate hearing on the ‘Equal Rights’ issue by a 5’5” Tlingit woman.”

Making History

The Alaska Territory passed women’s suffrage in 1913, seven years before the 19th Amendment, and their laws against discrimination passed nearly 20 years before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, banning discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. But it was Elizabeth Peratrovich who led the charge to end discrimination against Indigenous Alaskans.

She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1956, and died in 1958, a year before Alaska became the 49th state. She was buried in the shade of a Sitka spruce in Juneau’s Evergreen Cemetery; her husband was laid to rest beside her in 1989. Every year, the groundskeeper opens the protective posts that block street access to the graves for just one day — February 16th, the date the Alaska Equal Rights Act was signed into law — to commemorate Elizabeth Peratrovich Day.

The Alaska House of Representatives named a gallery in her honor, and a bronze bust sculpted by her son, Roy Peratrovich, Jr., rests on a black walnut wooden base in the lobby of the State Capitol. He also worked with author Annie Boochever on a biography of his mother, Fighter in Velvet Gloves, published in 2019.

That same year, The New York Times published a belated obituary: “Overlooked No More: Elizabeth Peratrovich, Rights Advocate for Alaska Natives.” A year later, the U. S. Mint released five million $1 coins commemorating her. They featured Peratrovich’s portrait, the title of the 1945 legislation, and the symbol of the Tlingit Raven moiety (descent group) to which she belonged.

Even the cyberworld honored her in their own way with a 2020 Google Doodle illustrated by Alaska-based artist Michaela Goade showing Peratrovich at a podium, protected by the wings of the Tlingit Raven. And the Marine Parking Garage in downtown Juneau now sports a vibrant 60-by-25-foot mural featuring Peratrovich with a modern version of the crest of her clan painted by artist Crystal Kaakeeyaa Worl and her apprentices.

The Smithsonian Institution, in its National Museum of the American Indian, now houses the Petratrovich family papers, from 1929-2001. The collection includes correspondence, personal papers, audio recordings of radio interviews, and news clippings related to the civil rights work done by Elizabeth and Roy Peratrovich.