Once upon a time, a “large, plump, hard-boiled, shrewd” woman named Nila Mack was asked by Columbia Broadcasting System to reinvent a Saturday morning children’s radio show called “The Adventures of Helen and Mary.” Her first reaction? “Really? You want the childless widow to save your kids’ show? I don’t even like kids.”

To make a long story short, they did … and she did. That show became “Let’s Pretend.” A Saturday morning staple for 20 years, it won numerous awards and turned the childless widow who claimed she didn’t even like kids into The Fairy Godmother of Radio.

“Let’s Pretend” aired during the Great Depression, its fantasy world offering young listeners an escape from the harsh realities of poverty and radio news when the news was anything but good. And the woman responsible for the show was actress, radio writer, director, and producer Nila Mack.

Born in Kansas, Mack was the only child of a dancer and a Santa Fe Railroad engineer killed in a train wreck when his engine derailed in 1907. To support herself and her daughter, Mrs. Mack ran a dancing school in her home, where Nila — already well known in the community as an entertainer in local programs — accompanied the class on piano.

Mack attended Ferry Hall in Illinois. Known for educating the daughters of the mid-western elite, its liberal arts curriculum included uncommonly-taught subjects for the time such as science and math. After graduating, she went to Boston, where she took courses in French, dance, and voice training.

Theaterical Repertory Company

Her first professional break was as an actress in a traveling repertory company. It was there she met and married her leading man, Roy Briant, in 1913. The couple settled in Chicago, where they collaborated in writing movie scripts. While Briant was eventually offered a job in California as a screenwriter for Paramount Pictures, Mack continued to tour until she joined actress Alla Nazimova’s film production company. In the 1910s and ’20s, Nazimova was one of the brightest lights in American cinema and the theater. She cast Mack in two of her films — the 1916 pacifist silent film War Brides, and Toys of Fate in 1918.

But in 1927, Mack received a call to come to California to care for her husband, who had become ill. Briant died in December of that year, leaving Mack widowed at the age of 35.

She moved back to New York and busied herself with work, returning to vaudeville, where she performed many of her own pieces. In the late ’20s, while playing in the Broadway comedy “Fair and Warmer” and Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House,” she wrote scenarios for movie shorts. Her first brush with radio came in 1929 when she joined Columbia Broadcasting System as an actress in an experimental program titled Radio Guild of the Air.

Kansas Radio Station

But just as her fledgling movie career had been interrupted, so, too, were her first steps into radio. In 1930 she returned to Kansas when her other became ill, becoming program director of a local radio station — a job that marked the start of a long, successful career in radio programming. Mack never failed to credit WEEB for providing her “basic training” — selling and writing copy for a show, twisting dials, announcing, performing, and directing. Although she worked long hours for little pay, the experience was priceless.

But CBS remembered her. Within six months, they reached out with an offer to assume responsibility for their Saturday morning kiddie show, “The Adventures of Helen and Mary” — a bigger job at a better salary than she ever expected — and she returned to New York. Quoted as saying, “Really? You want the childless widow to save your kids’ show? I don’t even like kids,” she took on the job of retooling the station’s struggling program.

Fantasy and Classic Fairy Tales

But Mack didn’t just retool it. She remade the show from the bottom up, with a new title, new format, and new program content. Renamed “Let’s Pretend,” it focused on fantasy and classic fairy tales that transported children to faraway lands and peaceful, enchanted forests, if only for half an hour a week.

With a belief that fairy tales served as children’s guides to life’s simple, eternal truths, her fairy tales preached the triumph of goodness over evil. Her princes were charming; her dragons fiery; courtesy and kindness mattered; the good guys always won, and each story taught a lesson. And because she didn’t think it was fair to keep children in suspense from week to week, battles were always fought in the middle of the half hour, the villain receiving his just desserts at the end. During its 20-year run, the series aired more than 300 fairy tale adaptations in addition to original scripts.

And in what was a major innovation for its time, Mack turned casting on its ear by insisting the roles in every story be played by children. She oversaw auditions, eventually assembling a cast of 40 child actors ranging in age from six to 16 who were paid $3.50 per broadcast. From those auditions, she discovered and nurtured young talents who would one day become performers, directors, and writers.

Launched TV and Film Careers

Among them were Dick Van Patten of the TV series “Eight is Enough”; Ann Francis, who starred in “Honey West”; Walter Tetley, a.k.a. Leroy on “The Great Gildersleeve”; and versatile British actor Roddy McDowell.

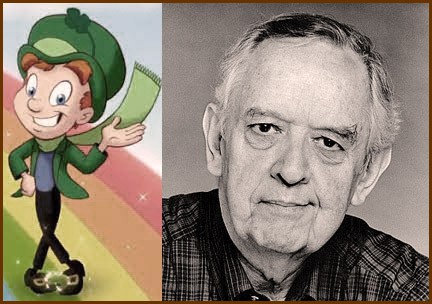

Another young cast member, Arthur Anderson, would one day write a history of the show titled Let’s Pretend & The Golden Age of Radio. Today we know him as the voice of Lucky the Leprechaun in Lucky Charms cereal commercials. He credited Mack with understanding how important it was for a cast of child actors to convey the openness, innocence, and simplicity she wanted for “Let’s Pretend,” and believed her genius for choosing and working with a young cast was the secret to the show’s surviving longer than any other dramatic program on American radio.

In 1943, Newsweek described Nila Mack as “large, plump, hard-boiled and shrewd.” But Anderson saw her as “a lone woman in a man’s world” where “hard-boiled and shrewd” were assets. After all, there weren’t many female directors during the Golden Age of Radio. But Nila Mack warranted an office on the 14th floor of CBS just down the hall from Edward R. Murrow. The most influential and esteemed figure in American broadcast journalism during its formative years, listeners knew him by his signature sign-off during World War II, “Good night and good luck.”

60 Awards in 20 Years of Broadcasting

With the success of “Let’s Pretend,” CBS appointed Mack its Director of Children’s Programs. During its 20 years of broadcasting, from 1934 to 1954, the show won almost 60 awards from radio magazines, women’s clubs, and school/college associations, including two prestigious George Foster Peabody Awards for “outstanding children’s program,” cementing her title as the real-life Fairy Godmother of Radio. Off-air, she collaborated with Theodor Seuss Geisel for the CBS radio adaptation of his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, published under the name Dr. Seuss.

For 20 years, the childless widow who claimed to never like kids educated and nurtured scores of talented young actors in radio’s dramatic arts while entertaining millions of America’s children with her scripts based on beloved fairy tales and fables. And while she may have come across as “hard-boiled and shrewd” to some, friends remembered her as high-spirited, humble and friendly, never turning away fans or autograph seekers.

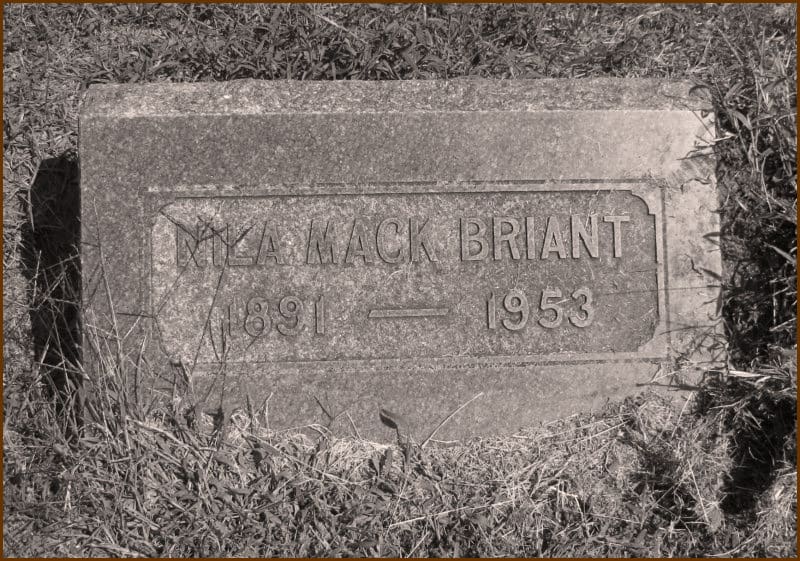

Nila Mack died of a heart attack in her New York City apartment in January of 1953. She was laid to rest beside her parents in her hometown in Kansas in Riverview Cemetery. As a testament to her talent and influence, the program she reinvented, “Let’s Pretend”, disappeared from the airwaves for good a year after her death.

Museum of Television & Radio

And though it took a while, she was a 2006 honoree of the Museum of Television & Radio’s She Made It: Women Creating Television and Radio, celebrating the achievements and preserving the legacies of women who have had an enormous impact on the media. Fifty-three years after her death, Nila Mack joins the ranks of notable women like Christiane Amanpour; Katie Couric; producer Linda Bloodworth-Thomason and Delta Burke, Dixie Carter, Annie Potts and Jean Smart, cast of Designing Women; Carol Burnett; Betty White; Shari Lewis; Dr. Joyce Brothers, and Judy Woodruff, to name but a few.