In an age when few women dared to color outside the lines, an irrepressible convent schoolgirl — tall and leggy, with big blue eyes, blonde Shirley Temple curls and a pet monkey, drove Model Ts around the world, landed a seaplane on an uncharted stretch of the Amazon River, and filmed travelogues that captivated armchair travelers the world over.

Idris Galcia Welsh was born in 1906 in Canada. In an effort to curb her daughter’s rebellious nature, her mother put her in a series of convent schools throughout Europe. But raised on a diet of boys’ adventure books from her stepfather’s library, Idris wanted nothing more than to explore the exotic worlds she found in their pages.

Writing of how she longed “to sleep with the winds of heaven blowing around my head, preferring the canopy of stars and the Mediterranean moon to the dust-catching, air-repelling draperies of school furnishings,” she got her wish in 1922, when she spotted an ad in The Paris Herald: “Brains, Beauty & Breeches — World tour offer for lucky young woman willing to forswear skirts and rough it in Asia and Africa. Be prepared to learn to work before and behind a movie camera.”

Life-changing ad

The ad was placed by a Polish expatriate born Valerian Johannes Pieczynski, who renamed himself Walter Wanderwell and granted himself the rank of Captain.

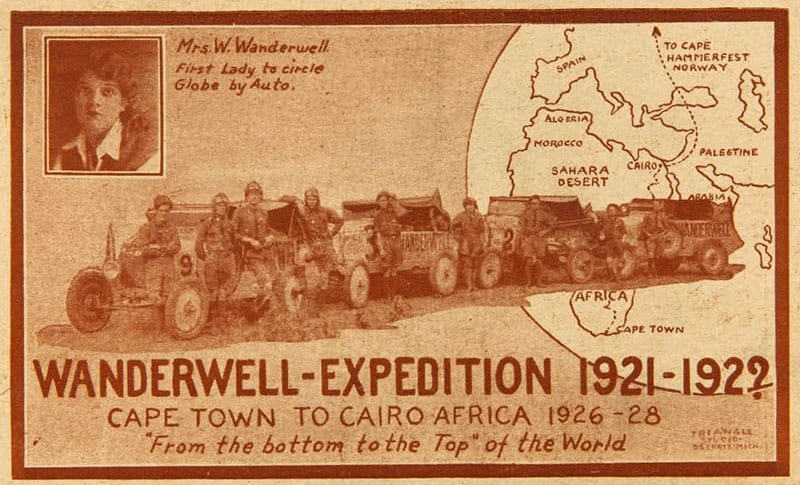

An explorer, itinerant filmmaker, savvy promoter and felon, Walter Wanderwell spent most of World War I in a U.S. jail on suspicion of being a German spy. After his release in 1918, he and his wife founded something called the Work Around the World Educational Club (WAWEC), billed as a lofty effort to promote world peace and the newly-formed League of Nations.

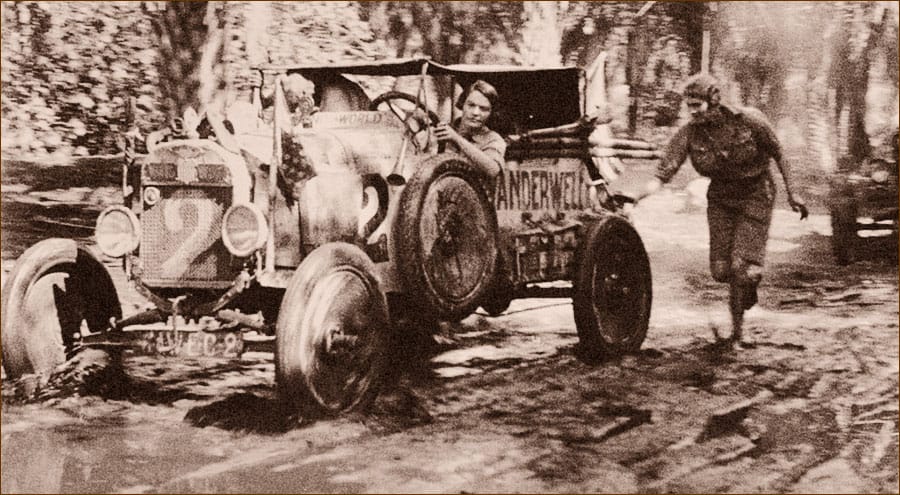

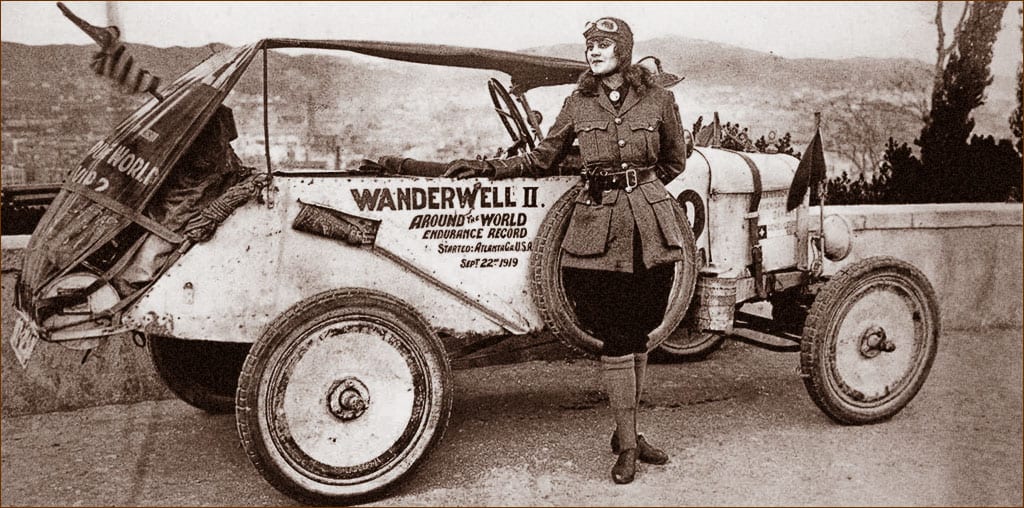

By the early ’20s, he was making headlines with his Million-Dollar Wager — a Ford-sponsored, round-the-world automotive race between teams racing Model-Ts. The first team to visit the most countries and log the most miles would win a cash prize. At a time when good, serviceable roads were scarce and cars were unknown to much of the world, the whole idea seemed foolhardy. Nonetheless, the Captain and his crews set out in Model Ts modified with gun scabbards and sloping backs that folded out, accordion-style, into traveling darkrooms.

Aloha Wanderwell is born

With her mother’s permission and her sister in tow as chaperone, Idris Welsh applied for and got a job with the expedition. For her, it must have seemed like the chance of a lifetime. And for 25-year-old “Cap” Wanderwell, the timing couldn’t have been better.

By 1922, he and his wife had separated, and he needed a translator, driver and secretary for his great adventure — not to mention a fresh face for his travelogues. At 16, Idris Welsh was tall, blonde, and good looking, with a swagger and self-confidence befitting a twenty-something. And since Wanderwell’s films and public lectures financed his travels, he recognized a gold mine when he saw one.

Welsh signed on as a driver, mechanic, translator and filmmaker. But, before long, “Cap” made her the centerpiece of the expedition, complete with a brand new name — Aloha Wanderwell. Never mind there was still a Mrs. Wanderwell out there.

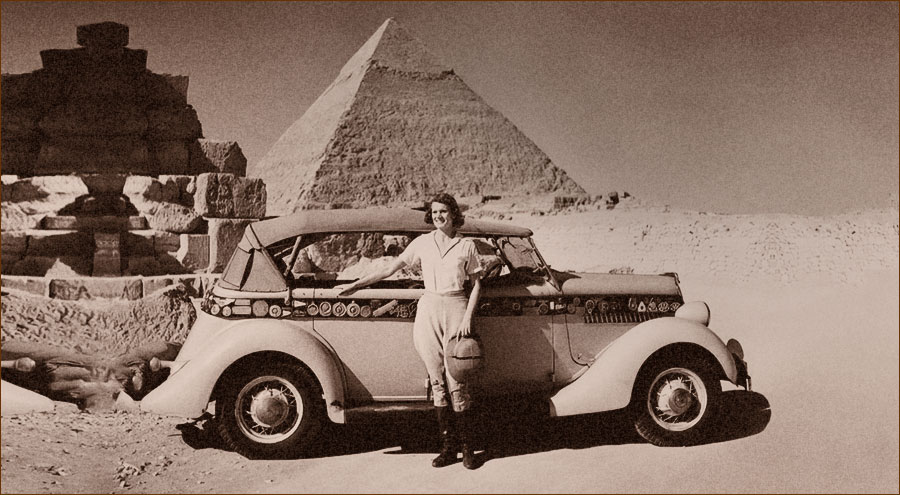

With her new name, and dressed in the expedition’s official uniform — military-style jacket, jodhpurs, white shirt, leather jerkin, aviators cap and goggles, Aloha Wanderwell set off on her first automotive journey, starting in France in 1922 and ending in the U.S. Territory of Hawaii in 1925.

The parade of Fords traveled through China, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Palestine, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sudan, Switzerland, Turkey, Yemen and the Soviet Union — where Wanderwell was named the “first demoiselle to pilot a motorcar to Siberia.” In 1924, they even crossed paths with five American fliers attempting the first aerial circumnavigation of the globe, with Aloha filming their meeting.

Crushed bananas and elephant fat

Wherever they went, Aloha put her training as a mechanic to good use, swapping kerosene for gasoline, using crushed bananas to grease the gears, and a mixture of water and elephant fat for engine oil. In a 1982 interview with American Cinemeditor magazine, she recalled film crews editing footage in local hotel rooms, rewinding with pencils in the reel hubs, and trading with local vendors and Ford dealers for gas and services in exchange for endorsements of their “finance-as-you-go” expeditions and talks, held in venues as grand as a movie theater in Istanbul and as rickety as a tin shack outside an African diamond mine.

The Wanderwells arrived in California in 1925. After “Cap” returned from Florida, where he took care of a few pesky details like divorcing his wife, he and Aloha married. Turns out he was still on the FBI’s radar; marrying Aloha prevented his arrest under the Mann Act, which prohibited transporting young women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Their marriage produced two children, Nile and Valri, raised by Aloha’s mother throughout their travels.

Pontoon plane pilot

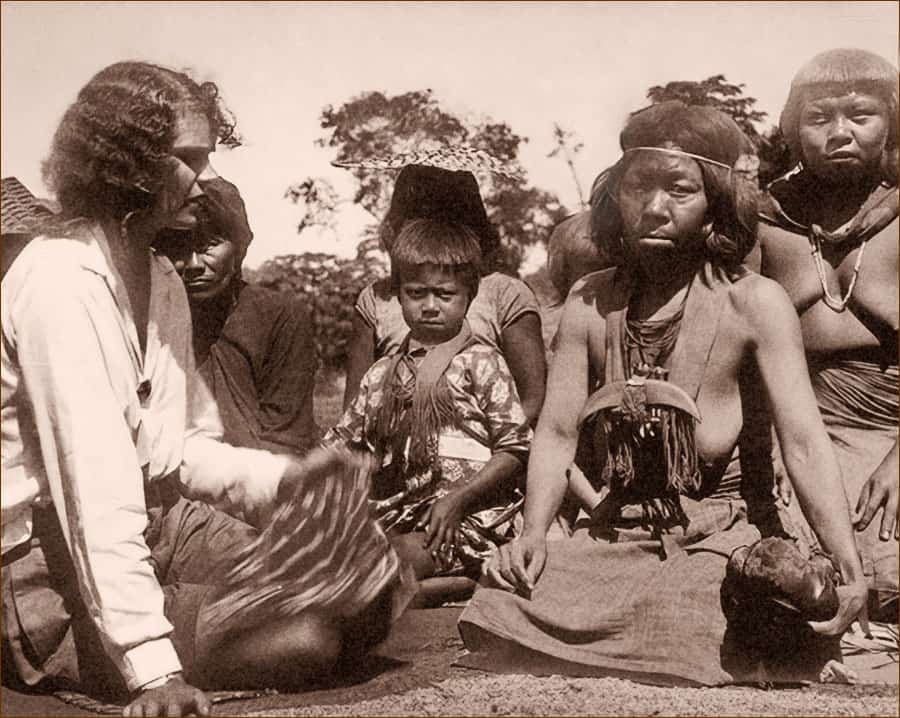

Aloha’s greatest adventure happened in 1931, on an expedition headed to Brazil in search of British explorer Percy Fawcett, who disappeared in 1925 while searching for a lost city in the Amazon. Aloha by now had also learned to fly a pontoon plane. When it ran out of fuel, she landed it on an uncharted run of the Amazon in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, once known as Brazil’s wild west, where she was met by the indigenous, little-known Bororo people.

And just as she did everywhere she went, Aloha Wanderwell charmed the Bororos, getting their permission to film their culture and daily lives. The expedition didn’t find its man, but it returned with footage for three travelogues — The Last of the Bororos and Flight to the Stone Age Bororos (now in the Smithsonian’s Human Studies Film Archives), and their only theatrically-released sound film, The River of Death, now in the Library of Congress.

Mysterious Murder & the Rhinestone Widow

You’d think someone who had logged 380,000 miles, crossed six continents and covered over 50 countries would have had enough drama in her life. But by 1932, Aloha and her husband were living apart — she in Los Angeles and he aboard their 110-foot yacht, the Carma, being outfitted in a harbor near Long Beach, CA, for a South Seas expedition, when “Cap” was murdered.

A man boarded one night asking to see Wanderwell when a group of passengers directed him to a cabin where “Cap” was consulting charts. A shot rang out and people scrambled, some seeking the mysterious stranger. Instead, they found Walter Wanderwell slumped against a banquette, shot dead with a .38 slug through his back, but no sign of the gun or the shooter.

Known as a philanderer, rumored rumrunner and scam artist, plenty of people may have wanted “Cap” dead. Even Aloha was questioned. She showed little emotion and seemed unsurprised by her husband’s murder, leading the press to nickname her “the Rhinestone Widow.” A disgruntled former crew member was eventually arrested, tried and acquitted. The case went cold and, to this day, remains one of California’s greatest unsolved murder mysteries.

As for Aloha, “Cap” left a measly estate valued at $1,500 — nowhere near what a newly-widowed mother of two needed to raise a family. But when it came to promotion and re-invention, Aloha Wanderwell had learned a thing or two from her husband. She promptly put the sensational publicity surrounding his murder to good use with the release and promotion of a 28-minute version of The River of Death to reviews ranging from “a good adventure” with “excellent human interest sequences and some fair thrills,” to simply “anemic.”

The new husband

Once all the brouhaha died down, Aloha married her second husband, a man named Walter Baker, in 1933. During their marriage, which lasted more than 60 years, they traveled to New Zealand, Australia, Hawaii, India, Cambodia and Indochina, shooting and producing three films, including Explorers of the Purple Sage, shot in Wyoming.

Capitalizing on the newest technology, the Technicolor film included the only known footage of Desert Dust, a legendary wild palomino stallion who eluded capture until 1945. Becoming a famous rodeo horse, his story inspired the Wild Horse Protection Act of 1959 and, later, the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971.

By the 1940s, her travels behind her, Aloha Wanderwell Baker continued to lecture and write, and published her autobiography, Call to Adventure!, which was republished in 2012. And while America’s fascination with Captain Wanderwell and his Million-Dollar Wager had long faded, Aloha’s star never seemed to dim.

A larger-than-life figure of self-invention, legend and controversy, she held audiences in thrall, lecturing about her improbable adventures as grainy, black- and-white silent travelogues played in the background.

She presented her last lecture and film screening at the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History for 150 family members, guests and curators in 1982. As always, she appeared in full expedition gear, a leather flying helmet slung casually over a blanket roll. And after asking audience members how they traveled, and getting the expected answers — by car or airplane, Aloha proceeded to enchant them with clips and tales of her travels in the long-ago days before commercial airlines and webs of interstate highways.

She died at her home in 1996, at the age of 89, just one year following her husband’s death. At her request, she was cremated, her ashes buried at sea.

Aloha Wanderwell’s remarkable life and career speaks to the power of self-invention, savvy marketing, ambition, and a woman who had the gumption to defy society’s limitations at a time when few dared.

‘Amelia Earhart of the open road’

She was a pilot, a film star, an ambassador for world peace, a filmmaker, and the centerpiece of one of California’s biggest unsolved murder mysteries. She charmed the elusive, indigenous Bororo people and rubbed elbows with Hollywood elites like Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. Dubbed the “Amelia Earhart of the open road” by the media, she was the first woman to drive around the world (Harriet White Fisher was the first to circumnavigate the world by car in 1909-1910 but, unlike Wanderwell, she was driven by a chauffeur).

Despite having directed and appeared in 11 filmed travelogues, you won’t find her in the Women Film Pioneers Project website of 200 silent filmmakers. Her films are scattered among the Academy Film Archive, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress, while the Detroit Public Library houses 10 boxes of Wanderwell papers, postcards and negatives in its National Automotive History Collection.

Thanks to Heather Linville, Academy Film Archive film preservationist, new generations are learning about Aloha Wanderwell through frequent screenings of restorations like those at an AFA-sponsored Orphan Films program in New York in 2014, and the Women and the Silent Screen conference in Pittsburgh in 2015. And Wanderwell’s grandson, Richard Diamond, who maintains an extensive website about his legendary grandmother, donated her collection of photos, scripts, diaries, journals, scrapbooks and text memorabilia to the AFA’s Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills, with her collectibles — some 280 auto badges, parts of cars she drove, leather film cases and her wardrobe — going to a future Academy Museum so Aloha Wanderwell can finally take her rightful place in film history.