Who didn’t love celebrity chef Julia Child? After all, she made French cuisine accessible to America’s cooks with her 762-page cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, and brought one of the first cooking shows, The French Chef, into countless living rooms. But if you think she was the mother of modern French cooking, you would be wrong. That honor belongs to Eugénie Brazier.

First woman

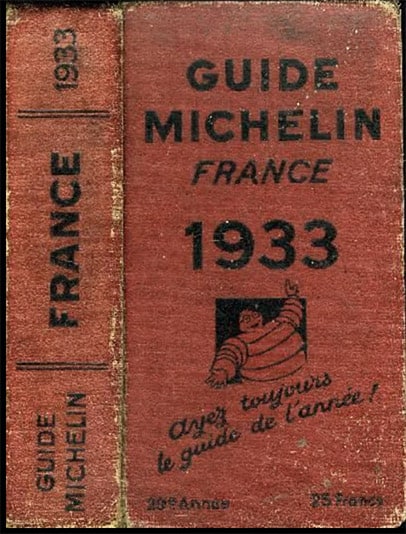

In 1933, Brazier was the first woman to be awarded three Michelin stars, and the first person in the world to hold six Michelin stars simultaneously — a record she held for over 60 years.

The little red Michelin guide book began encouraging drivers to take road trips to local attractions back in 1900. Among the attractions were restaurants. Considered a hallmark of fine dining by the world’s top chefs, the highly-coveted stars are awarded to restaurants Michelin considers the best of the best, and convey immense prestige. Three Michelin stars is the most prestigious honor, meaning the restaurant has exceptional cuisine and serves distinct dishes executed to absolute perfection.

But more than that, Eugénie Brazier is also one of history’s most influential, yet overlooked, chefs who helped shape gastronomy into what we know today.

Born in 1895 on a farm near Lyon, France, she grew up knowing poverty and hard work. It was her job to tend the family’s pigs, rising before the sun to keep an eye on the snuffling porkers. But in telling stories of her childhood, it was always the delicious dishes of her youth she recalled. One of them was a soup her mother brought out to the fields while she was tending the pigs. It was simple — a broth of leeks and vegetables cooked in milk and water, enriched with eggs, and poured over stale bread to give the dish more substance. But Brazier remembered she had “never eaten better.”

Although she had very little formal education — she could only attend school in the winter, when it was too cold for the pigs to run loose, she was a curious child, always up for a challenge, of which there were many. Her mother died suddenly when she was just 10 years old; she had a child out of wedlock at age 19; and she survived two World Wars.

Beginning in a Bakery

During World War I, she worked as a nanny for a family in Lyon who owned a bakery. She eventually took over the kitchen as their cook simply because she enjoyed working at the stove. But, much as she loved the job, her need to support her son, Gaston, led her to a tony establishment called La Mére Fillioux, whose kitchen was “always women only.” They were known as les méres Lyonnaise (the Lyonnaise mothers), a reference to the home-style cuisine they offered. But don’t let that seemingly simple description fool you. These were the women who gave birth to Lyon’s gourmet reputation and put the city on the map when it came to exceptional cuisine.

It was there Eugénie Brazier learned what would perhaps become her signature dish — “Poultry in Half-Mourning.” It was a whole Bresse chicken (pedigreed chickens from the former French province of Bresse, long considered the best table chicken in the world) with slices of black truffles artfully tucked between the flesh and skin. It got its name, “half mourning,” because some of the bird’s white flesh could still be seen.

The truffles perfumed the meat as it poached in chicken stock before the dish was finished with a cream-enriched sauce made from the reduced cooking liquid. Another favorite dish was her “Beautiful Lobster of Dawn,” a whole sweet lobster drenched in brandy and rich cream.

Seven years later, in 1921 when she was 26, Brazier was able to purchase a small tavern and grocery store in Lyon for a handful of francs, calling it La Mére Brazier. Her opening day menu was simple — crayfish with mayonnaise, and pigeon with peas followed by flambéed apple-filled brioche for both lunch and dinner. The decor was sparse; but the crisply-pressed linen and sparkling silver and crystal gave her tables a classic, understated elegance. Women waited tables. The wine came direct from the region’s local winemakers, since Brazier never hired a sommelier. And as her reputation grew, so did that of the restaurant. In the dozen or so years before it won its first three Michelin stars, it won over the palates of the finest gourmets of the time, becoming a culinary destination for French presidents, international prime ministers and Hollywood celebrities like Marlene Dietrich.

First 6 Michelin stars

Eugénie Brazier earned her first six Michelin stars after working in a professional kitchen for just 15 years. By that time, she was 38 and chef-owner of two restaurants — one in Lyon, the other in an old wooden structure that had once been home to a hunting camp nestled in the foothills of the French Alps. Those two establishments held six Michelin stars for 20 years and one of them — the original La Mére Brazier, for 28 years.

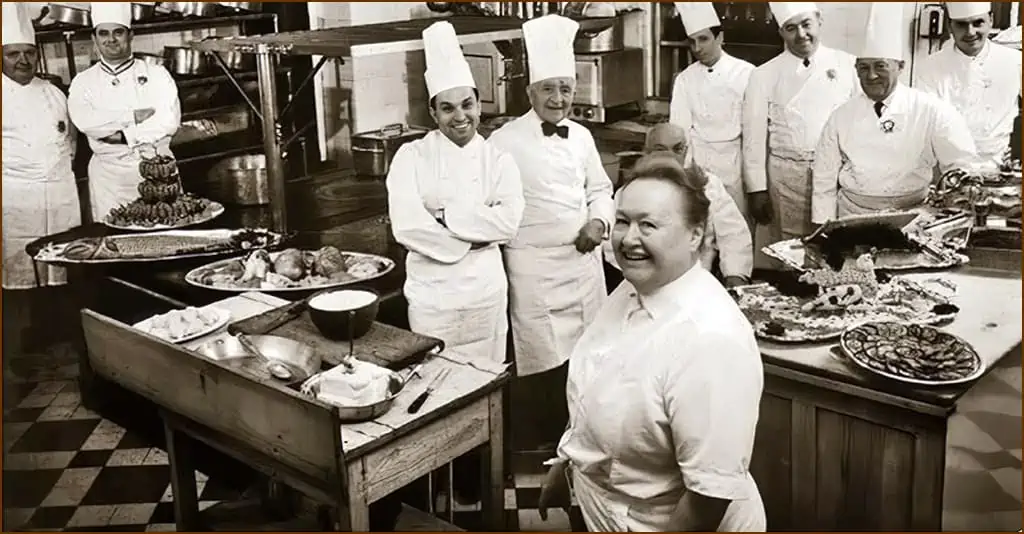

An imposing, rather stout woman whose hair was pulled up in a bun, Brazier was always immaculately clad in white cotton shirts whose collars were always buttoned and whose sleeves were always rolled up. Her white cotton apron had big scoop pockets, and there was, more often than not, a towel at her waist. No matter how busy she was in her kitchen, it wasn’t unusual for her to leave the stove to greet guests as they arrived.

Sharp-eyed perfectionist

A perfectionist who ran her kitchens with a sharp eye, Brazier could be found most mornings carefully inspecting the dining rooms, linen and cutlery. Fastidious about cleanliness and cooking, her refrigerators and freezers had to be emptied and cleaned daily. And, just as she never trusted a sommelier to choose her wines, she never stinted on the quality of her ingredients; one local poulterer groused about her demanding nature, saying that soon “his poultry would have to be manicured before delivery.”

Described as one of the most formidable chefs in history, when it came to cooking she wrote, “it’s not complicated … you just have to be well organized, remember things and have a bit of taste.” As simple as that sounds, her dishes were anything but. Her famous Bresse chicken with truffles was described as a “rich and aromatic masterpiece,” and Elizabeth David, Britain’s foremost writer on food and cookery, described her cooking as “calm, elegant and seemingly effortless.”

It was not in Eugénie Brazier’s nature to be a celebrity chef. Modest, and always mindful of her humble beginnings, she once said, “I have met and conversed with many intellectuals, sophisticates, and I have always been mindful of who I am. I instinctively stop myself from putting my feet on ground that is not mine.” In fact, her 1977 New York Times obituary remembered her for turning down a citation for the French Legion of Honor because, “it should be given out for doing more important things than cooking.”

Left out of history

Perhaps it was her humility that kept her out of the culinary history books. She left the spotlight to others. So much so that the narrative for the history of modern French cooking belongs to Paul Bocuse, known as the King of French Cuisine and a one-time student of Eugénie Brazier, and his male peers. In The Great Chefs of France, considered THE chronicle of French gastronomy in the 1970s, Brazier is mentioned only in passing. And in 2007’s Food: The History of Taste, all her male peers are included … but not her.

In March of 1998, a New York Times headline even erroneously proclaimed it was Alain Ducasse, French chef and co-founder of the French Culinary School, who achieved “A First for Michelin Guide: One Chef Wins Six Stars.” It took the Times five days to issue a correction and give Brazier her due.

Then there is the matter of sex. In retrospect, the 1930s were a high point for women when it comes to culinary history. Bocuse, in a 1970 interview, famously said he’d rather have a woman in his bed than behind the stove in his restaurant — a blatant sexist attitude that has long persisted in the culinary world.

Eugénie Brazier cookbook

Just two years before her death at age 81 in 1977, Eugénie Brazier began working on what would be her first and only cookbook. Unfinished for decades, her family finally picked it up and shepherded it through to completion, publishing it in French under the title Les Secrets de la Mére Brazier (The Secrets of Mother Brazier), in 1977. Second and third editions followed in 1992 and 2001 respectively. The English version, La Mére Brazier, came out for the first time in 2014. In addition to its 300 classic recipes, it is equal parts history, photos and tributes that firmly fix Brazier in culinary history — all the more important once her story faded after her death.

But during Brazier’s lifetime, renowned French gastronome Maurice Edmond Sailland, known by the pen name Curnonsky and dubbed the Prince of Gastronomy, called her the greatest chef in the world. Even Bocuse referred to her as “one of the pillars of global gastronomy.”

The original restaurant in Lyon, La Mére Brazier, was run by her family after her death, but is now owned by Michelin-starred chef Mathieu Viannay, who has retained her original decor and still features her classic dishes on the menu. In 2003, a street closest to the restaurant at 12 rue Royale, not far from the Louvre Museum, was renamed rue Eugénie-Brazier by the Lyon City Council.

In 2007, some 30 years after her grandmother’s death, Jacotte Brazier founded L’association des Amis d’Eugénie Brazier (The Association of Friends of Eugénie Brazier) to promote the careers of young female apprentices, guide and support them in “the very masculine world of cooking,” and keep her grandmother’s professional values alive. And, naturally, in the age of the internet, Brazier was honored on June 12, 2018, what would have been her 123rd birthday, with a Google Doodle.

Finally, a 2019 documentary about female chefs titled The Heat: A Kitchen Revolution, by award-winning filmmaker Maya Gallus, was released, writing Eugénie Brazier back into history as it focused on her as the predecessor of and role model for today’s generation of seven female chefs who appeared in the film.