As one of the first black families to settle in mostly-white Mecosta County, Michigan, thanks to the 1862 Homestead Act, Dr. Vernie Merze Tate’s great-grandparents were trailblazers. So it’s only natural she blazed her own trail, this time using education to break racial and gender barriers while amassing an impressive list of “firsts” along the way.

Early Life

Tate started school at age five in a one-room schoolhouse on the corner of her family’s large farm. Later, she walked miles of dirt roads through the pines to and from Blanchard High School, memorizing poetry, the Gettysburg Address and details of historic battles to pass the time.

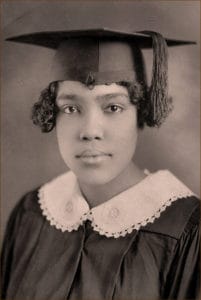

But when her high school was destroyed by fire and students were forced to “graduate” at the end of the 10th grade, Merze Tate, at age 13, was one of the graduates. The youngest, and the only African American in her class, she was named valedictorian.

When she realized her 10th-grade education wasn’t sufficient for college admission, she left home at 15, working as a domestic to save money and graduate from Battle Creek High School. Maintaining a straight-A average and graduating in 1922 with a tuition scholarship to Western State Teachers’ College (now Western Michigan University), she became that school’s first African American graduate.

College and Jim Crow

Vernie Merze Tate graduated from Western State in 1927 with a solid academic record that put her in good stead in her search for a teaching position. But she soon discovered Jim Crow was alive and well in her home state — Michigan, at the time, didn’t hire black teachers to teach in its secondary schools.

She found a job in Indianapolis, teaching history and civics at the Crispus Attucks High School, founded when the Ku Klux Klan was on the rise and segregationists demanded a separate high school for black students. Tate was hired by the school principal specifically to teach his students to excel beyond the founders’ intentions.

It was also at Crispus Attucks she began sharing a lifelong passion by exposing her students to the value of travel through the Merze Tate Travel Club, now known as the Merze Tate Explorers. Tate also put her summer breaks to good use, studying at the Teachers College of Columbia University to earn a Master’s Degree in history in 1930.

On to Oxford

Two years later, she killed two birds with one stone when a $1,000 fellowship from Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority allowed her to travel abroad to study at Oxford University. But first, she had to pass the screening process of the American Association of University Women who, until then, hadn’t admitted black women.

Not only was Vernie Merze Tate accepted into Oxford’s graduate program; she earned a Bachelor of Literature degree in international relations in 1935, becoming the first black female to receive a degree at Oxford. And while she took full advantage of all the social, intellectual and cultural opportunities Oxford offered, she also learned how to ride a bicycle for the first time.

While in Europe, Tate traveled to Germany, France and Switzerland. Fluent in five languages, she studied German at the University of Berlin. But when Hitler rose to power, she knew it was time to come home. Her travel experience came in handy when she volunteered to help prepare military officers for duty in World War II by training them in the languages and cultures of France and Germany.

From Harvard to Howard

It was after attending a Harvard University graduation with a friend that Tate decided to pursue her Ph.D. She read the titles of the graduates’ dissertations, confident her work at Oxford would more than measure up. The very next day, she met with the Dean of the Radcliffe graduate school to begin work on her Ph.D. And so it was that Merze Tate added another “first” to what was becoming quite a list: she became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in government and international relations from Harvard University’s Radcliffe College in 1941.

Her path took her to teaching positions at several historically black colleges before she arrived at Howard University in 1942, where she was hired as the first black female historian in its Department of History. Dr. Tate would spend the next 35 years at Howard.

International Relations and Diplomacy Expert

A prolific writer, Tate authored books on European diplomacy, the history of Hawaii, power struggles in the Pacific, nuclear weapons and disarmament. In 1948, she was chosen as one of three Americans, and the only African American, to represent the United States at the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), where she used her expertise in disarmament to counsel General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 1950-51 to teach geopolitics in India, Tate used the opportunity to make her first of two round-the-world tours, logging a total of 44,000 miles. She taught and lectured throughout India, as well as in Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong and the Philippines. She was also commissioned by the U.S. State Department as a photographer, filmmaker and researcher, producing travelogues of the places she visited. Circling the globe, she always traveled solo, accompanied, as she put it, only by her camera.

Retirement and an Out-of-this-World Legacy

Dr. Tate retired from Howard University in 1977. She went on to serve on the committee of the Black Women Oral History Project, consisting of interviews with 72 African American women from 1976-1981, and worked with the Salary and Promotions Committees at Howard University, focusing on the inequities in academia she had experienced as a woman in a male-dominated environment. A member of Phi Beta Kappa, she was conferred several honorary degrees from universities where she had studied and taught.

Never married, Dr. Vernie Merze Tate died of cardiac arrest in Washington, DC, at age 91 in 1996. She was buried next to her mother in a plain pine coffin in Michigan’s Pine River Cemetery. Her hometown dedicated its Tate Memorial Library in her honor.

Her legacy speaks to the power of education as a passport to success. She left something few African American women of her time could generate — a rich historical archive now housed at Howard University. In 1999, the Ladies’ Home Journal named her one of its “Most Influential Women of the 20th Century.”

And the Merze Tate Explorers, which grew out of her long-ago Merze Tate Travel Club, offers today’s girls the opportunity to explore the world through college and career opportunities as they study abroad, visit Fortune 500 companies, and meet their female leaders.

But as well-traveled as Dr. Tate was, there was one trip left on her bucket list. When Pan-American Airways (at the time, the leader in global flights) offered tickets for their well-advertised “First Moon Flights” Club after the wildly-popular Apollo 8 mission in 1968, Merze Tate purchased her ticket. The airline expected their civilian flights to take off for outer space sometime around the year 2000. Sadly, Pan-Am stopped booking flights to the moon in 1970 and, within 20 years, had declared bankruptcy.