It was a classic case of “anything you can do, I can do better,” set in the magnificent Canadian Rockies in 1904 when Gertrude “Truda” Benham, at 36, set out to satisfy her wanderlust by climbing as many Rocky Mountain peaks as she could before summer’s end.

The mountains rising from Moraine Lake at Banff National Park’s Valley of Ten Peaks were simply numbered 1-10. Benham decided to start with Peak #1, or the 10,613-foot Mount Heejee as it was known. Unbeknownst to her, renowned American climber Charles Fay had also arrived with his eye on Peak #1. The Geographic Board of Canada had asked Fay to pick a mountain he’d like named for him; he chose Heejee, and determined to be the first to the top.

Beating a male rival

Fay and his guide set out bright and early, only to abandon the climb in the face of heavy snow and dangerous rock fall. What he didn’t know was that Benham and her guide had already bested him, having reached the summit of Mount Heejee using a different route.

Suffering the indignity of having been beaten by a girl, a mightily disgruntled Fay eventually settled for what would be the second ascent of what today is, nonetheless, known as Mount Fay. By the time he reached its summit, Gertrude “Truda” Benham had already been there, done that, and moved on to the western slope of the Rockies, where she went on to climb Mt. Gordon, Mt. Balfour, Mt. Collie, and become the first woman to stand atop the summit of 11,870-foot Mt. Assiniboine. Today, Truda Peaks, at 10,007 feet, are part of Mount Rogers in British Columbia’a Glacier National Park.

Childhood Alpine trips

London-born Gertrude Benham was born in 1867, the youngest of six children. She was “bitten with a love of the mountains” as a child when her father, a master iron manufacturer, took her on summer Alpine trips. While little is known about her early life, we know she cared for her aging parents until their deaths in 1891 and 1903 when, at age 36, she came into a modest inheritance that allowed her to scratch her travel itch.

And so it was she found herself in Canada, having seen pamphlets for the newly-accessible Rocky Mountains. By the time she scooped Charles Fay, she was already a skilled climber, with more than 130 ascents to her name, including Mont Blanc and one of the best-known mountains in the Alps — the Matterhorn.

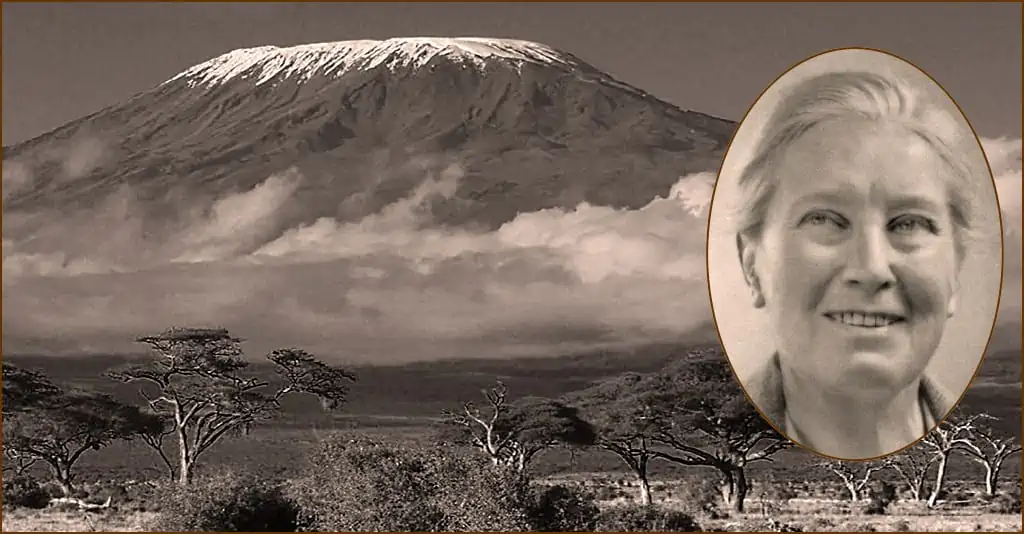

Kilimanjaro skeletons

Gertrude Benham made more than 130 Alpine ascents and climbed more than 300 peaks 10,000 feet or more in every part of the world before she was done. She was the first woman to summit 19,000-foot Mount Kilimanjaro in 1909, completing the climb on her own when her guides left her upon seeing a pile of skeletons they interpreted as a sign of “evil spirits.”

But Benham wasn’t just a mountaineer. She was an intrepid hiker and globetrotter of the first order, logging seven trips around the world by steamship, rail and on foot. One trek in 1908 took her from Valparaiso, Chile, to Buenos Aires, Argentina. The next year she logged 600 miles in Central Africa, walking from Zambia to the southern tip of Lake Tanganyika. It was from there she continued to Kilimanjaro.

Malaria in Calcutta

Wherever she went, she was accompanied by her Bible, copies of Lorna Doone and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, a pocket Shakespeare and her knitting. She sold her needlework to pay for articles she collected along the way, most of which represented native crafts. The only time she fell ill in her travels was when she contracted malaria in Calcutta thanks to tears in her mosquito net. She even managed to avoid a shipboard outbreak of cholera while crossing the Bay of Bengal during a cyclone.

Her travels took her to Canada, Fiji, New Zealand, Tasmania, Australia, Japan, India, Egypt, Japan, America, Chile, Brazil, Zambia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, India, the South Pacific, Niger, Cameroon, Uganda, Rwanda, Malawi, Mozambique, Tibet, Syria, the East Indies, Hong Kong, Belize, the West Indies, Trinidad, New Hebrides, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Myanmar and China.

Royal Geographic Society

Elected to the Royal Geographical Society in 1916, she resigned after six months when, according to The Times, its staid, science-minded writers refused to publish a paper she had written on African volcanoes that included lively descriptions of local people and scenic views.

She kept records of her extensive travels in journals, along with sketches, paintings and photographs. While her photos and artwork have yet to be discovered (not part of any known Benham archive, descendants believe they were stored in a trunk in a warehouse destroyed by the blitz of Plymouth in World War II), memorabilia and many of the cultural artifacts she collected can be found — alongside a pair of well-worn hiking boots — at the Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery in Devon, England. The collection of more than 800 objects includes artifacts from almost every country in what was once the British Empire, including jewelry, costumes, accessories, metalwork, lacquerware, ceramics, toys and religious articles.

Buried at sea

It was 1935 when she set off on what would be her eighth and final round-the-world trip before finally settling down in a little bungalow she had built on the south coast of Britain. Three years into the journey, she died aboard ship off the coast of East Africa at age 71, and was buried at sea. Her passing was marked by The Times in an obituary dated December 16, 1938:

“News has reached us of the death and burial at sea off the West Coast of Africa last February of Miss Gertrude E. Benham, the traveller. Miss Benham made a remarkable journey across Africa in 1913. Her entire outfit was contained in seven loads, and apart from the native carriers whom she hired from place to place, she had no companion, and was absolutely unarmed. She crossed Africa, passed on to India, and was in the Himalayas when War broke out and altered her plans. She had on a previous occasion carried out a similar expedition from South Africa up to what is now Kenya Colony. Miss Benham was an intrepid climber, and had many first ascents to her credit. She was the first woman, and probably the first English climber, to reach the summit of Kilimanjaro. On this occasion, she did the last 4,000 feet without any companion. In 1932 she wrote for The Times a vivid description of how, after an arduous ascent, she waited six days for the clouds to roll away in order to make a sketch of the second highest peak in the British Empire, Kamet.”

Overlooked by media

Gertrude “Truda” Benham once described herself as a “very quiet and harmless traveler.” Never one to blow her own horn, she was an early 20th-century woman traveling alone to some of the most far-flung places in the world. As such, her accomplishments were easily overlooked by the media. Even in her journals, she played down her accomplishments, simply noting “favourable” days on the mountains with “grand and distinct views.”

While she spent but one summer in the Canadian Rockies, she reached the summits of more peaks that short season than many climbers do in a lifetime. And while her ascent of Mount Kilimanjaro alone should have earned her a place in the record books — being, as The Times said, “the first woman and probably first English climber” to reach its summit — few histories of that mountain even mention her name.