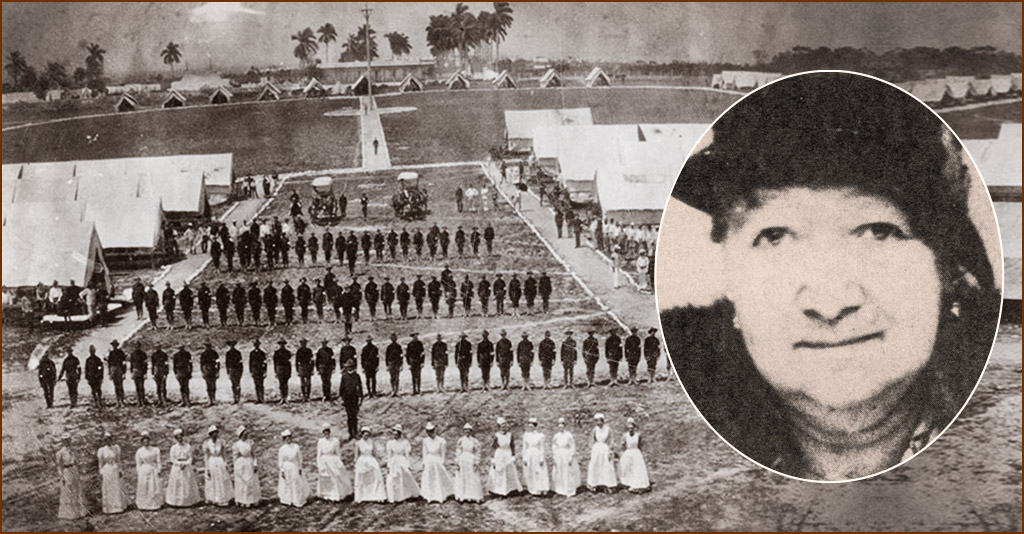

As wars go, the Spanish-American War gets very little attention. But black women hired as nurses during what some called the “splendid little war” get even less. So you’re excused if you’ve never heard of a woman with the unusual name Namahyoke “Namah” Sockum Curtis, and her role in the Spanish-American War.

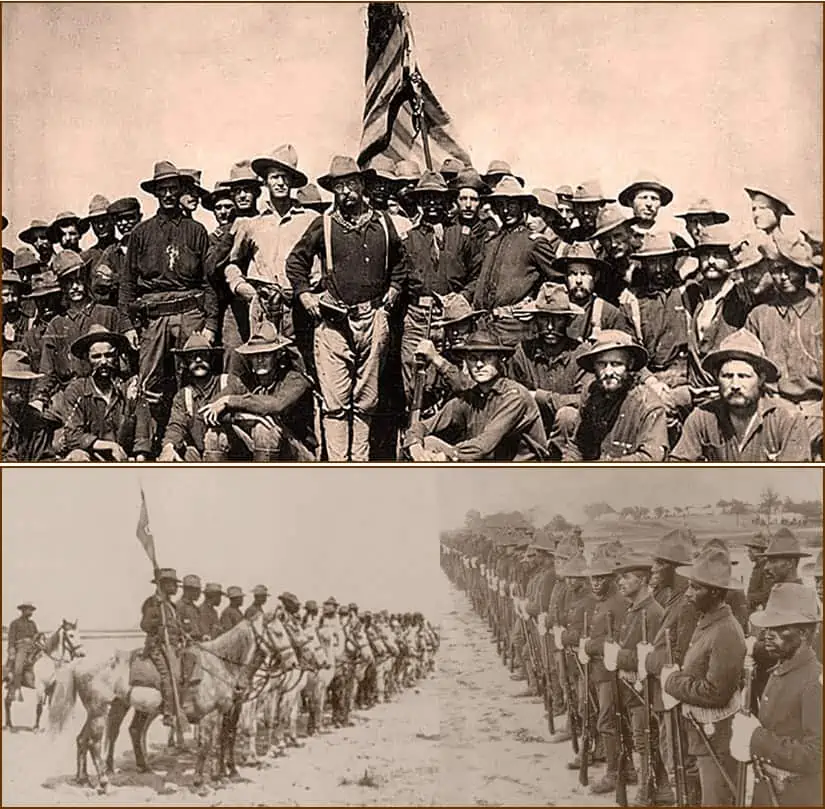

Briefly, the Spanish-American War began in April, 1898, when America intervened in Cuba’s three-year struggle for independence from Spain after the USS Maine blew up in Havana’s harbor. “Remember the Maine!” became a rallying cry as America declared war on Spain. And Theodore Roosevelt, leading his “Rough Riders,” made a name for himself in a war that ended just 16 weeks after it began, with the Treaty of Paris in July. So how does Namahyoke Sockum Curtis fit into all this?

Namahyoke Sockum Curtis was born in California, one of seven children. Her maternal grandfather was African American; her father was a Native American from New Mexico’s Acoma Pueblo tribe. Raised by an aunt, Namah attended grade school in San Francisco, then graduated from the Snell Seminary for young women in Oakland in 1888 — one of the best-known and most fashionable schools on the West Coast.

Black society prominence

After graduation, she traveled to Philadelphia to visit relatives. While there, she met Austin M. Curtis, a graduate of nearby Lincoln University, and they eloped in May of 1888. After their marriage, she returned to her family in California while her husband attended Northwestern Medical School. But when her family learned of the marriage, they sent her to join her husband in Chicago. The couple went on to have four children, becoming one of the most prominent couples in black society at the time.

While in Chicago, Namah Curtis joined a movement to fund and establish a hospital where African-Americans could receive advanced medical treatment. And in January of 1891, Provident Hospital and Training School, the first black-owned and operated hospital in America., opened its doors. Dr. Austin Curtis became its first intern and, later, its visiting surgeon. The couple remained in Chicago until April of 1898, when Dr. Curtis was appointed superintendent of the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC.

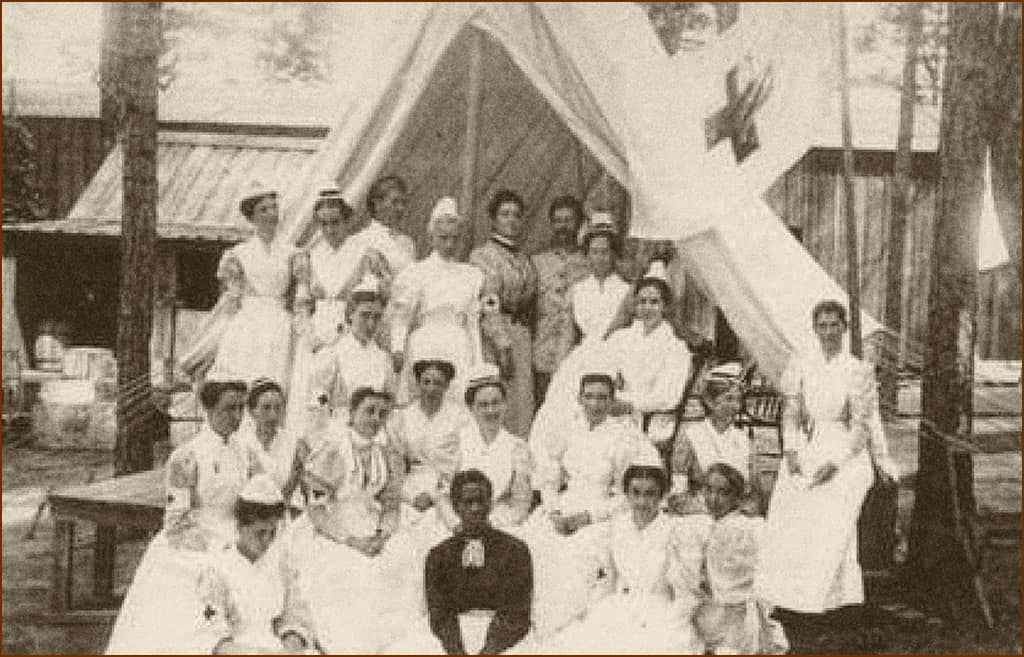

Later that month, Congress declared war on Spain. But the Army was ill-prepared for a war in the tropics, especially when it came to organizing medical services. The troops suffered from rampant outbreaks of malaria, typhoid, yellow fever and dysentery; while fewer than 400 soldiers died in combat, more than 10 times that number are thought to have succumbed to disease during and after the war. Hospital corpsmen were male recruits with no professional training while, back home, the U.S. had been training professional nurses since the 1870s. So in 1898, the surgeon general was authorized to employ contract nurses to fill a critical need.

Politically savvy and competent

He selected Namahyoke Sockum Curtis to recruit nurses for the military. Seen as an ideal candidate for the mission, she was prominent in social and civic affairs, well educated, and politically savvy. Active in the women’s division of the Republican National Committee, she had campaigned nationwide for President William McKinley a year earlier. And, as a community leader in Chicago, she had worked to establish Provident Hospital. So although she was not a professional nurse, she was knowledgeable about the medical profession.

And because she had recovered from yellow fever herself, she was presumed to be immune. Due to a widespread belief that blacks were immune to tropical diseases like yellow fever and malaria, the medical community sought out nurses of color as early as the 1793 yellow fever epidemic. So Curtis left for New Orleans and other southern cities known to have had previous outbreaks of yellow fever. Her special duty? Find women to serve as “immune nurses.”

Ignored in the historical record

Women responded from Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama and Florida, many claiming to have nursed during the Civil War. But few had the training the Army had required up to that point, when black women were only 2% of professional nurses, according to the U.S. census. Namahyoke Curtis recruited 32 of the 80 black contract nurses. Most of her recruits went to Santiago, Cuba, to serve in the worst of the epidemics, sailing on July 19, 1898, to “Cuba’s fever camp to save Uncle Sam’s men,” as The New York Times once described it. By war’s end, the nurses had served in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, the Philippines, on the hospital ship Relief and in military hospitals on the mainland. Yet their presence is largely absent in the military’s official records and archival material.

The Spanish-American War was the first in which nurses served in a dedicated, quasi-military unit, and the first time they were fully accepted in military hospitals. While no nurses were killed in combat, 153 died from disease acquired during the war, including two supposedly immune African American nurses — Isabella Bradford and Minerva Turnbull. They worked 14-hour shifts with 20-minute lunch breaks and provided their own uniforms, which they had to launder and maintain. Duties included dressing wounds, administering medications, giving ice baths, preparing and serving food, and attempting to maintain proper standards of hygiene and sanitary conditions in tents, fields and overcrowded buildings. Their pay was $30 a month, plus meals and lodging.

Hurricane and earthquake relief

After the war ended in July of 1898, Curtis continued her service, directing her attention to rescue and relief activities during natural disasters. In 1900, when a Category 4 hurricane tore through Galveston, Texas, killing 6,000-8,000 people and producing a 15-foot storm surge that flooded the city, she volunteered for a relief squad of the American Red Cross under the direction of Clara Barton. Six years later, she was commissioned by William H. Taft, secretary of war at the time, as part of the relief work for victims of the San Francisco earthquake and resultant fires that killed over 3,000 people and destroyed over 80% of the city.

Namahyoke “Namah” Sockum Curtis was given an official commendation for her work in the Spanish-American War, bringing with it a lifetime government pension. She died in 1935 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. If you visit, you will find a rough-hewn, grey granite monument dedicated to the memory of those women who nursed the wounded and sick during this brief conflict in America’s history, erected by the Order of Spanish-American War Nurses in 1905. Their performance led to the establishment of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901.

This was my great Grandmother. I have followed in her footsteps participating in relief activities. I am the CEO of ICEBUDDY Systems, Inc. a global healthcare company.