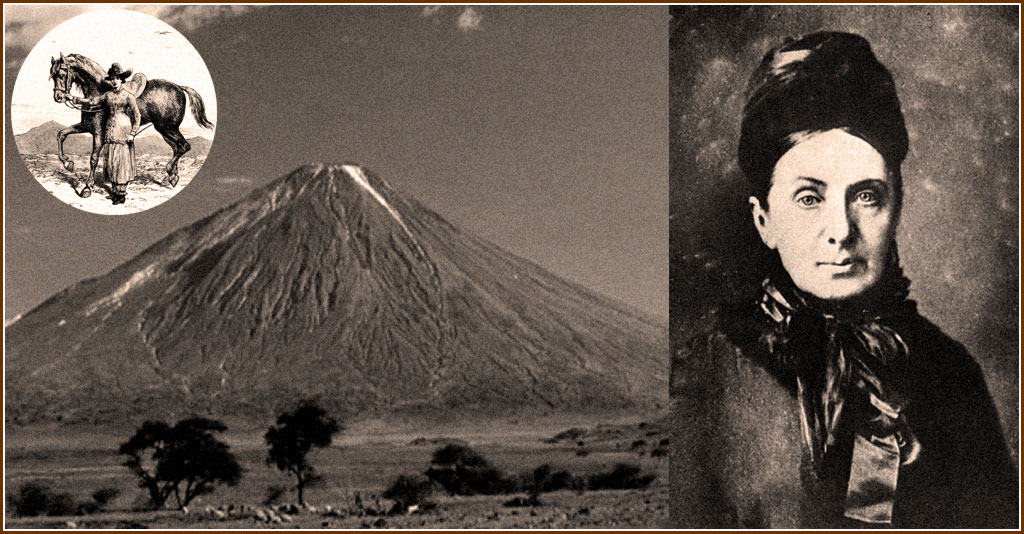

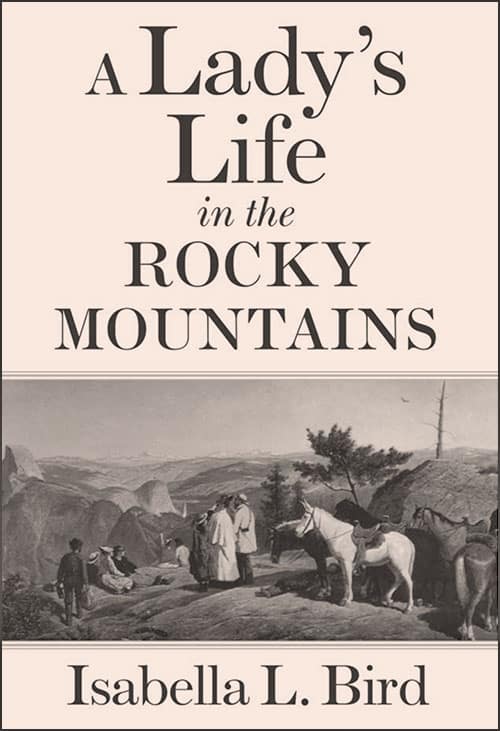

In 1972, a bespectacled, shaggy-haired singer-songwriter named John Denver celebrated his love affair with Colorado in a song called “Rocky Mountain High.” But more than a century earlier, an intrepid Englishwoman named Isabella Lucy Bird beat him to it. Her book, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, was published in 1879 as a letter to her sister in England. It detailed her adventures in Colorado, became an international bestseller, and put the area now known as Rocky Mountain National Park on the map.

Born in 1831, Isabella Bird was the small, sickly child of a clergyman. When doctors prescribed fresh air and outdoor activity, her parents encouraged her to take up rowing and horseback riding — sidesaddle, of course. With an insatiable curiosity and a keen eye for detail, she put her time outdoors to good use, studying her surroundings, then writing about them.

Curative sea voyage

At 18, she had spinal surgery for what’s been described as a fibrous tumor– a risky procedure that left her with bouts of depression and insomnia. This time, when her doctor prescribed a bracing sea voyage to cure what ailed her, her father gave her £100 and his blessing to travel wherever she liked until the money ran out. She booked passage on a steamer to Canada and the northeastern United States, staying for several months. Fiercely independent and determined to do things her own way, the fact that parts of New England were in the midst of a cholera outbreak when she arrived in 1854 didn’t seem to deter her.

She returned home to write her first book, The Englishwoman in America, published in 1856 when Bird was 25. Her father died two years later, when she, her sister and mother moved to Edinburgh, Scotland — the place Isabella Lucy Bird would always call home. But it was when their mother died and the sisters suddenly had to fend for themselves that Bird decided to travel in earnest for reasons other than her health. She would travel for a living and support herself by writing about her adventures.

Hawaiian mountain climbing

Despite periods of poor health and chronic back pain, nothing dampened her enthusiasm. In 1872, en route to Australia, she decided at the last minute to disembark in Hawaii (then known as the Sandwich Islands) where, for six months, she met royalty and spent time with everyday islanders who taught her to ride astride — which, to her delight, eased the back pain she had suffered from years of riding sidesaddle, like a proper Victorian lady. Before leaving the islands, she climbed Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa, two vast volcanic mountains with an altitude of nearly 14, 000 feet. Her second book, Six Months in the Sandwich Islands, published in 1875, treated readers back home to detailed descriptions of everything from Hawaii’s flora, fauna and foods to its glorious climate, its churches and the lives of its people. It is now considered a classic of Hawaiian literature.

Eventually leaving Hawaii for California, she made her way from San Francisco to Lake Tahoe, then on to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. In addition to being fascinated by its rough, rugged territory, people had told her its crisp, clean, mountain air would do her good. Apparently, they were right — upon her arrival in 1873, she wrote to her younger sister, “ESTES PARK!!! … everything that is rapturous and delightful … The very place I have been seeking.”

Today, Rocky Mountain National Park rangers hail Isabella Lucy Bird as the “Mother” of the region. But award-winning journalist and editor of Backpacker Magazine, Tracy Ross, profiled her in 2019 for the Estes Park blog, describing her as “America’s first badass literary mountain woman.” And for good reason.

Rugged going in the Rockies

Bird traveled 800 miles through the Rockies on horseback, once riding through a blizzard that froze her eyes shut. She was snowed in in a primitive, two-room log cabin with two young law students hired to escort her, all the while being wooed by the cabin’s owner — a lonely, one-eyed (thanks to a fight with a grizzly bear) desperado named Jim Nugent, a.k.a. Mountain Jim. Bird described him as “a broad, thickset man with a revolver sticking out of the breast pocket of his coat … subject to ‘ugly fits’ when it’s best to avoid him.”

She even climbed 14,259-foot Longs Peak, the highest point in Rocky Mountain National Park, wearing her version of a traditional Hawaiian riding dress (the pa’u) suitable only for the tropics — a fitted jacket, ankle-length skirt and full pantaloons she gathered into a pair of borrowed hunting boots — in temperatures that fell below zero, after which a humiliated Bird described Mountain Jim “dragging [her] up, like a bale of goods, by sheer force of muscle.”

Told “there’s nothing Western folk admire so much as pluck in a woman,” pluck is something Bird seems to have had in spades, since she easily won over the rough, unruly men she rubbed elbows with. Mountain Jim (“a man any woman might love but no sane woman would marry”) was absolutely smitten. And seasoned ranchers considered her as good a cattle driver as any man.

Her book, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, came out in 1879. It sold like hotcakes in the eastern United States and Britain, where armchair explorers devoured her keen, detailed descriptions of Colorado’s rugged beauty, majestic scenery and colorful characters. Still in print, the latest edition is available from the University of Oklahoma Press, complete with footnotes, photos and Bird’s own sketches.

In 1876, Isabella Lucy Bird sailed into the port of Yokohama, Japan, to research a country little known in the West and introduce it to her audience. But as a preacher’s kid, firmly grounded in the value of spreading Christianity, she was also keen to investigate the potential for missionary work. Accompanied by a translator, she stayed seven months, covering about 2,800 miles by horseback, rickshaw and, when all else failed, on foot. The record of her journey was published four years later, its title a real mouthful: Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: An Account of Travels in the Interior Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrines of Nikko and Ise.

Hawaiian Royal Order

On her return home to Scotland, she met Edinburgh surgeon John Bishop, her sister’s doctor, in 1880. Shortly after losing her beloved sister to typhoid fever, she accepted a marriage proposal from the good doctor. They married in 1881, the same year King Kalakaua awarded her the Royal Order of Kapiolani, which recognizes service in the cause of humanity, merit in the sciences and art, or services rendered to the kingdom of Hawaii.

They were married just five years before Dr. Bishop died in 1886, leaving his widow a considerable inheritance. She used some of the money to study medicine at London’s St. Mary Hospital, planning to travel as a missionary, and almost became qualified as a physician, leaving just short of completing her studies. Still, considering her own lifelong familiarity with illness and disease — not to mention having been married to a doctor — she felt sufficiently qualified. From then on, she always traveled with a medicine chest of “the most compact make … with 50 bottles of ‘tabloids,’ a hypodermic syringe and surgical instruments for simple cases,” along with quinine for malaria, bandages and cotton. She also took time to learn photography, which she put to good use; her later books are beautifully illustrated with her own photos.

Into the Himalayas

She eventually set out on another journey, this time to India, where she visited missions and saw Ladakh, one of the most stunning parts of the Himalayas in the Kashmir region bordering Tibet — an area only half a dozen white Western women had ever seen. While there, she worked with Dr. Fanny Jane Butler, England’s first fully-trained female physician to travel to India, to establish two hospitals — the Henrietta Bird Hospital and the John Bishop Memorial Hospital, honoring her sister and husband, on land given to her by a maharaja.

She was in Korea at the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894. In Manchuria, she photographed Chinese soldiers heading for the front. Traveling China’s Yangtze River by sampan as far as she could before taking an overland route, she was stoned and attacked as a “foreign devil” by a mob that set fire to a hut where she sought shelter, rescued at the last minute by a group of soldiers sent by a local official. As if that weren’t enough, it was during this leg of her journey that her horse lost its footing in a river crossing — the horse drowned, while Bird suffered two broken ribs. Her adventures were recalled in her last book, The Yangtze Valley and Beyond, published in 1900.

Six-month caravan

By now in her fifties, Isabella Lucy Bird was still not ready to unpack her bags. She went from northern India to Iran with a group of British soldiers, then organized her own six-month caravan through northern Iran, Kurdistan, Armenia and Turkey before heading back to Japan, Korea and the Chinese Yangtze River valley. After witnessing atrocities committed against Armenians in the Middle East, she had an audience with British Prime Minister William Gladstone and addressed Parliament on the issue.

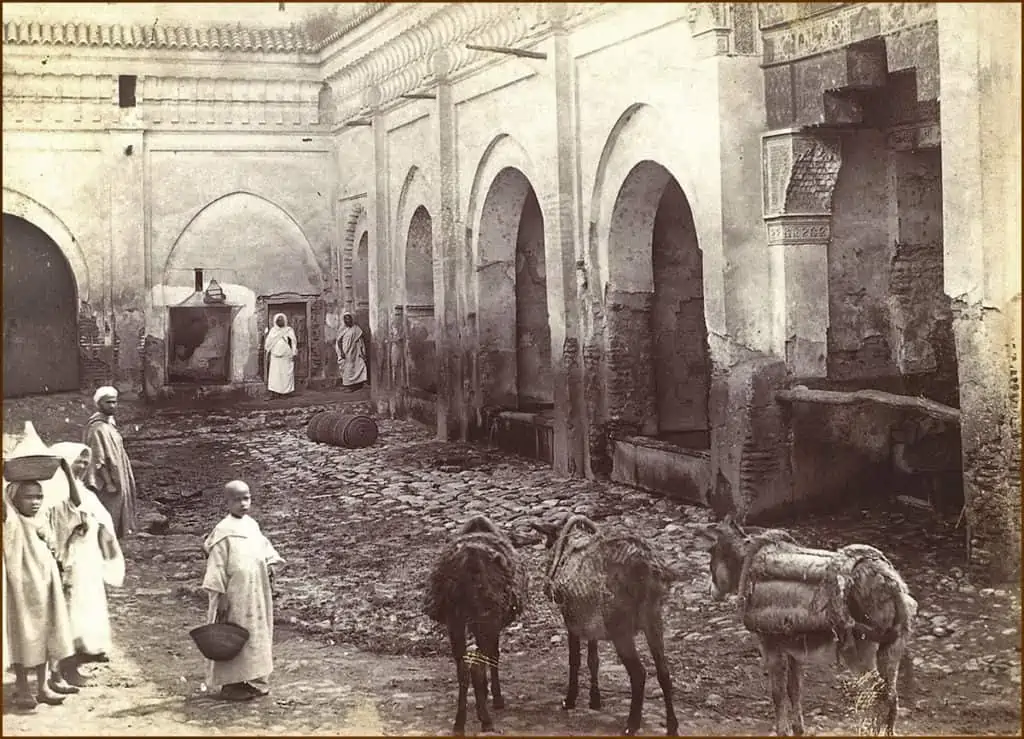

Her final trip was to Morocco, where she traveled with the Berbers (nomadic indigenous people of North Africa), and learned to use a ladder to mount a magnificent black stallion given to her by the Sultan. At nearly 70, she rode 1,000 miles, including through the Atlas Mountains.

Bird’s 1904 death

Several months after her return from Morocco, Isabella Bird became ill and died at her Edinburgh home in 1904. She was laid to rest in Dean Cemetery, just west of the city, alongside her parents, sister and husband. It’s said her camera, luggage and trusty medicine chest were already in London, packed and ready for one last trip to China.

By the time Isabella Bird was named the first female fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in 1890, accepted into the Royal Geographical Society in 1892, and elected to the Royal Photographic Society, she was already a household name to armchair travelers the world over.

Dubbed by the Times of London “the boldest of travelers,” she wrote 19 travel books. Living life on her own terms, unlike most Victorian women, she embarked on a series of extended journeys that took her to every inhabited continent except South America. While she didn’t circumnavigate the globe in one expedition, she traveled around the world before her death, including 800 miles by horseback through the Colorado Rockies and 1,000 miles through mountainous North Africa. Her insatiable curiosity, fierce determination and pioneering spirit set her apart as a role model who traveled the world, wrote about her experiences, spoke out against discrimination she witnessed, and showed compassion for some of the poorest societies of the world.

Inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 1985, today there is a Denver elementary school named for her. Its mission echoes the manner in which Isabella Lucy Bird lived her remarkable life: “To provide our diverse learners a compassionate, intellectually stimulating, vigorous learning experience that ensures their well-being, engagement, academic and personal success, and contribution as global citizens.”

What an incredible person. Her books are still available in print and audio. Very lucky a friend mention Bird to me.

Wow! What an amazing person. I’m glad to have learned about her.

I love this woman.

What a joy to read about her braver and adventurous