Louise Boyd wasn’t born with the proverbial silver spoon in her mouth. Hers was made of gold. Her grandfather made a fortune in the California Gold Rush of 1848; her father was a mining magnate with a stake in a gold mine, and president of San Francisco’s Boyd Investment Company. Her mother was a New York socialite.

Tomboy of Privilege

Growing up, Louise Arner Boyd had every advantage a young woman of privilege could imagine. Attending private schools in San Francisco, she was trained in the social graces with every expectation she would marry well and live the life of a wealthy socialite. But Boyd, who described herself as a tomboy, had an adventurous streak, following her two brothers in everything they did — horseback riding, hiking and hunting.

But her world changed when, in 1901 and 1902, both brothers died of rheumatic heart disease. Her father, left with no male heirs, began exposing Louise to his business dealings, teaching her how to handle money and oversee its careful investment.

Arctic Lure

Always fascinated with geography, Boyd idolized Roald Amundsen, Norwegian polar explorer and noted figure in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. At 19, she saw him arrive in San Francisco after completing the first sea voyage through the Northwest Passage. Although Horace Greeley may once have told young men to go West, Louise Arner Boyd had other ideas: “The charm and infinite diversity of the Arctic is its own reward. I have got the Arctic lure and will certainly go North.”

Heiress and Socialite

But, in yet another jolt, Boyd lost her mother in 1919 and her father in 1920. At age 32, single, and with no immediate family, she became sole heir to a $3 million fortune (about $39 million today) and the newly-minted president of the Boyd Investment Company.

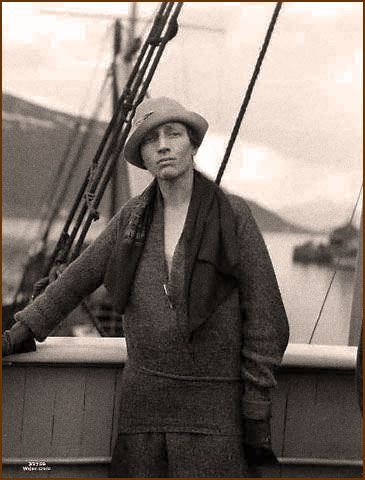

For several years, Louise Boyd led the life for which she was bred: that of a genteel socialite, hosting prominent guests, staging benefits for various charities at her Bay Area estate, Maple Lawn, and making the expected European tours with friends. All of which led, in 1925, to her presentation at Buckingham Palace to England’s King George V and Queen Mary. And while few in her circle knew she dreamed of a different life — that of a polar explorer, Boyd soon decided to use her considerable wealth to follow that dream.

Arctic Adventure and 11 Polar Bears

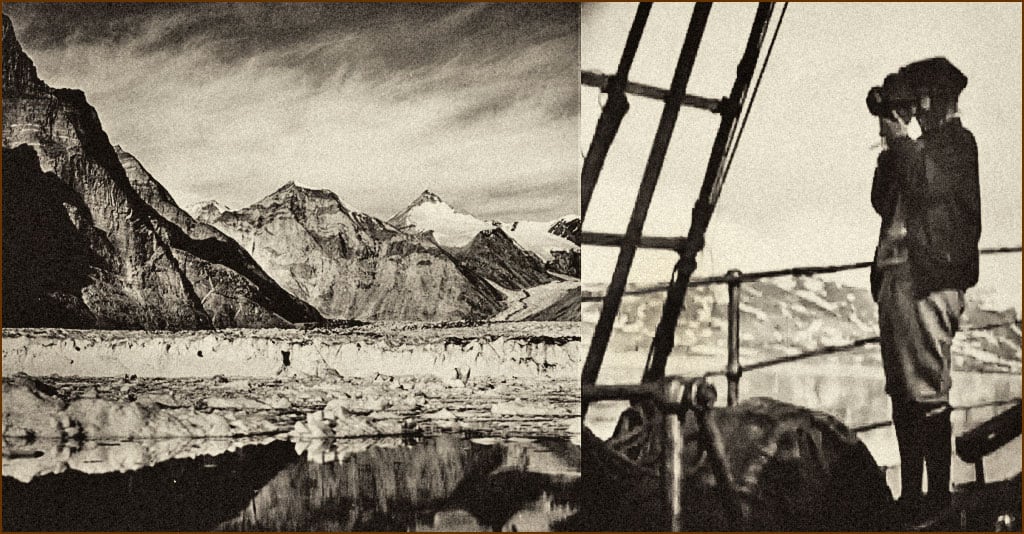

Boyd began to travel in the early 1920s. It was on a trip to Norway in 1924 that she saw the Polar Ice Pack for the first time — an experience she later recalled as having been instrumental in her life. So much so that, in 1926, she hired her own ship and crew, becoming the first woman to finance and lead an expedition to Franz Josef Land, high in the Russian arctic.

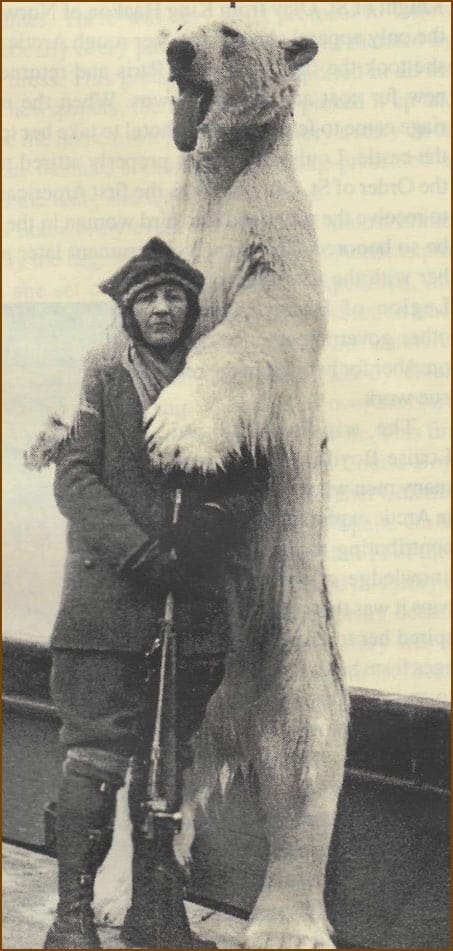

The ship was the Hobby, a supply ship once used by her hero, Roald Amundsen. Boyd and a group of friends set out on what was originally planned as a grand adventure — one that included a big game hunt in which Boyd killed 11 polar bears.

While today we consider big game hunting horrific, in Boyd’s time, it was highly respected. Natural history museums were just coming into their own, showing people who would never travel wildlife they would never see. So trophies like Boyd’s bears were brought back, stuffed, and displayed in settings that mimicked their natural habitat. Gaining notoriety for her exploits, Boyd was dubbed by international newspapers “The Girl Who Tamed the Arctic”.

But perhaps more important than her prowess with a rifle, the New York Times reported Boyd also shot 21,000 feet of motion picture film and 700 photographs on that one trip alone.

Life-Changing Search-and-Rescue Mission

Two years later, Roald Amundsen and his crew disappeared at sea while searching for fellow Italian explorer Umberto Nobile just as Boyd was ready to launch her second adventure to the Arctic in the Hobby. But Amundsen’s disappearance changed her perspective. As she put it, “How could I go on a pleasure trip when those 22 lives were at stake?”

Louise Boyd took part in the 10-week rescue mission, traversing some 10,000 miles in the Greenland Sea and into the pack ice north of Franz Josef Land. Just as she had two years earlier, Boyd filmed throughout the 10-week search-and-rescue mission — a total of 20,000 feet of motion picture film to be exact.

And though Amundsen and his crew were never found, Boyd was awarded the Chevalier Cross of the Order of Saint Olaf by Norway’s government — the first woman to receive that honor — and was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor. It was then Boyd committed herself not just to polar exploration, but to the pursuit of polar science.

The Best Equipment Money Could Buy

Throughout the 1930s, Boyd partnered with the American Geographical Society to explore uncharted polar regions and lead several expeditions, always bringing scientists with her to study and help interpret what she saw.

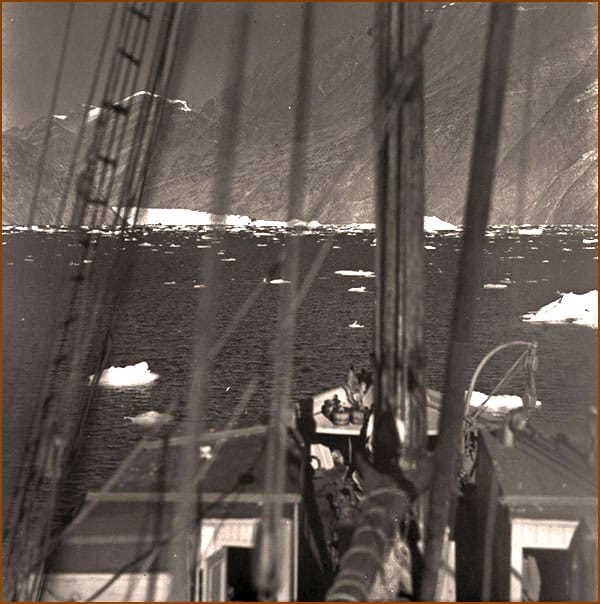

Conditions aboard the 125-foot, oak-ribbed sealers she chartered were far from luxurious, with no running water and a supply of mostly canned foods. But when it came to outfitting the vessels in pursuit of science, Boyd spared no expense.

She equipped her ships with echo-sounders to conduct topographical surveys, took tide gauge recordings, and used a specially designed wireless apparatus with its own expert in charge of experimental work on the effects of polar magnetism on radio communications.

Louise Boyd’s expeditions generated new data in the fields of geology, oceanography, botany and glaciology. She served as the official photographer on all her expeditions, documenting ice patterns along the Greenland coast. She was also a pioneer in the use of photogrammetry — the science of taking photos to create models or maps — in inaccessible places. Mapping previously uncharted regions of Greenland, she filmed and photographed the topography, sea ice, glacial features and land formations.

Louise Boyd Land

In recognition for her important work, a fjord in East Greenland was named for her in 1933, as was a mountainous region in Eastern Greenland — Louise Boyd Land is now part of Northeast Greenland National Park. The following year, she was elected as a delegate to the International Geographical Congress. And in 1938, Boyd was awarded the American Geographical Society’s Cullum Medal, becoming one of the first women to autograph their Fliers and Explorers Globe, signed by the 20th century’s major explorers and aviators.

Arctic Explorer/Secret Agent

With the outbreak of World War II, Boyd’s life took yet another turn. Her extensive knowledge gained through six expeditions to Greenland and the Arctic suddenly took on strategic significance and sensitivity. The U.S. government asked her to lead a geophysical expedition along the west coast of Greenland and down the coasts of Baffin Island and Labrador for the Department of Commerce’s National Bureau of Standards. She was named the Bureau’s consulting expert at a salary of $1 a year.

In June of 1941, a German torpedo sank a British cargo ship off Greenland’s southernmost point. In response, the Atlantic Fleet’s new Greenland Patrol mobilized to prevent Germany from establishing a base. At her own expense, Boyd chartered and outfitted the schooner Effie M. Morrissey, anchoring off the town of Julianehaab. As the locals came to meet the ship’s crew, they didn’t know what to make of the tall, well-dressed woman of a certain age who came ashore to huddle with a group of U.S. Naval officers.

Under the guise of her work as the world’s leading Arctic explorer and geographer, Louise Boyd carried out a covert government mission, searching for possible military landing sites and working on improving radio communications in the region. Her mission was so secret, even the captain of the ship she chartered was kept in the dark when it came to the expedition’s true goals.

The expedition returned to Washington, DC, in November of 1941 with valuable data. Throughout World War II, Boyd not only turned over to the U.S. War Department her photographic library and collection of hundreds of maps, but served from 1941-1943 as a special consultant to the Military Intelligence Division, for which she was awarded a Department of the Army Certificate of Appreciation in 1949.

One Last Expedition

Despite everything she had accomplished in her quest to go North, she had failed to reach her goal. So in what would be her last Arctic expedition, Louise Boyd chartered a plane and, in 1955, at the age of 67, became the first woman to fly over the North Pole. “North, north, north we flew. And in a moment of happiness which I shall never forget, our instruments told me we were there. Directly below us lay the North Pole.”

Final Years

Boyd returned home to the San Francisco area as a well-known figure and hostess who served on the Executive Committee of the San Francisco Symphony. But in her last years, she found herself in financial straits. Eventually, she had to sell her family home in San Rafael, along with all its furnishings. She divided her personal library among the universities of California and Alaska, and San Rafael’s Louise Boyd Natural Science Museum.

She spent her final years in a nursing home paid for by friends. While one source says Boyd spent most of her considerable fortune on financing and outfitting her expeditions, historian Elizabeth Olds wrote, “the evaporation of her wealth, particularly in view of her earlier sagacity and attention to careful investment, remains a mystery.”

Louise Arner Boyd died in 1972, two days before her 85th birthday. She asked that her ashes be scattered in the Arctic Ocean.

The Legacy of Louise Arner Boyd

An Arctic explorer who didn’t see snow until she was in her teens, Boyd’s legacy has proven to be priceless. Her films and photographic record have provided critical information to today’s climate change scientists and researchers, helping them understand how the ice has changed over the last century.

To have organized, financed and led seven Arctic expeditions, and contributed to the scientific knowledge about that region, is an amazing achievement. She also wrote two books on her research — 1935’s The Fiord Region of East Greenland and, in 1948, The Coast of Northeast Greenland (both available on Amazon).

Then there’s this. In 1974, the Center for Polar Archives at the National Archives acquired 150 reels of Boyd’s motion picture films, which she shot herself. By 1980, all those deteriorating nitrate reels had been copied to new safety film stock, preserved for use by today’s researchers and climate scientists.

Louise Arner Boyd once said, “People openly told me the Arctic was a place only for men — that for me to go where I did was not to be taken seriously. Determination and persistence brought me to the position I achieved.”