The shocking 1995 murder of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, often called the Queen of Tejano music, plunged fans into mourning and introduced her to English speakers who became fans. But few of them knew Selena stood on the shoulders of another woman, born 80 years before her death. That woman was Lydia Mendoza, rightfully known as the First Lady of Tejano.

Spanish for Texan, Tejano is identified with a Tex-Mex mix of folk and popular music that grew out of the Hispanic-descended Tejanos of South/Central Texas. Nicknamed “Lark of the Border,” Mendoza was the first star of recorded Tejano music whose 12-string guitar and pure voice made her a sensation throughout Latin America through the mid-1900s.

The second of eight children born to parents who fled the Mexican Revolution to settle in Texas, Mendoza crossed the US-Mexico border countless times as her father sought work to keep his family fed. In the 1930s, by the time she was 11, she was singing and playing guitar with her family’s band for tips on the streets and in the restaurants of San Antonio.

1934 radio performance

But Lydia was clearly the family’s standout star. Performing with them at San Antonio’s Haymarket Square in 1934, she was spotted by the host of a half-hour radio show, “La Vox Latina,” who approached her with an invitation to perform on radio. It took just two songs for the station’s phones to light up with requests for an encore. Once a local sponsor was found to keep her on the air for $3.50/week, Mendoza was on her way.

That same year, in a time when Mexican female solo recording artists were scarce, she recorded her first solo record for RCA’s blues/jazz Blue Bird label titled “Mal Hombre” (Bad Man). An immediate success on both sides of the border, “Mal Hombre” would become Mendoza’s signature song.

It set Mendoza on a hectic schedule of touring and recording. But she always made time to appear with her family and play for working-class Mexican-Americans and workers on the migrant circuit. Her audience saw her as the voice of the poor and downtrodden, singing in their vernacular — a language and dialect they understood. As Yolanda Broyles-González, author of Lydia Mendoza’s Life in Music/La Historia de Lydia Mendoza: Norteño Tejano Legacies, writes, she could bring the past to life and “entangle the listener.” Like American country music’s Carter Family captured the very heart of Appalachia in their songs, Mendoza’s audiences similarly heard their stories and everyday struggles in her music.

Sketchy agents

But despite more than 1,200 recordings to her credit, Lydia Mendoza’s career was one of ups and downs as she struggled with being a woman in a man’s world full of back-room negotiations between sketchy agents and slick promoters. Recording labels paid her just $15 a side for her early records, claiming she had signed her rights away. And considering the recording contracts were written in English, a language Mendoza didn’t read, they were probably right.

She put her career on hold in 1935 when her husband felt her place was at home, raising their three children. During World War II, gasoline rationing put an end to her touring while, at the same time, a shortage of shellac — no longer used just to produce records, but now in demand to make explosives — paused America’s entire recording industry for a few years.

1960’s career reboot

It was only when the war ended that Mendoza resumed her career, touring with her family and recording for the Mexican-American labels that had sprung up. But in the 1950s, Mendoza’s mother died and the family disbanded their act while they grieved their loss. It was only in the 1960s, following the death of her first husband and a second marriage, that she was able to pick up where she left off, despite by then suffering from arthritis. She continued to perform until being forced into retirement in 1988, when a series of strokes left her partially paralyzed.

Though her career spanned six decades, it was not until her later years that Mendoza was recognized for her contributions to Mexican-American music. She sang at President Jimmy Carter’s inauguration in 1977. And 22 years later she received the National Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton at a White House ceremony where she shared the stage with Aretha Franklin and TV producer-director Norman Lear, among others.

State and national awards

In between, she became the first Texan to receive the National Heritage Fellowship lifetime achievement award from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1982; was inducted into the Tejano Music Hall of Fame (1982) and the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame (1985). Posthumously, she was inducted into the Tejano R.O.O.T.S. (Remembering Our Own Tejano Stars) Hall of Fame and Museum in 2002, and awarded the Texas Medal of Arts by the Texas Cultural Trust in 2003.

Lydia Mendoza, the First Lady of Tejano, died of natural causes in 2007 at the age of 91 in San Antonio, where her career started, and was laid to rest in San Fernando Cemetery #2 before hundreds of Texans who came to pay their respects. In an honor not always granted to Latino artists by the English-language press, her obituary appeared in major newspapers on both coasts.

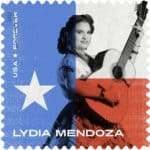

U.S. postage stamp

The United States Postal Service honored her with a Forever Stamp in 2013. And on the occasion of her 103rd birthday, a historical marker was unveiled at her gravesite in a cemetery attended by Mendoza descendants, including 13 grandchildren and assorted great grandchildren, along with dignitaries and 120 members of the public.

Lydia Mendoza didn’t just sing for those who had no voice. With her immense archive of recordings and one of the most remarkable careers for Mexican-American female singers, she gave rise to a fierce collective pride in the Hispanic community and blazed a trail for others like Selena to follow in the world of Spanish music.