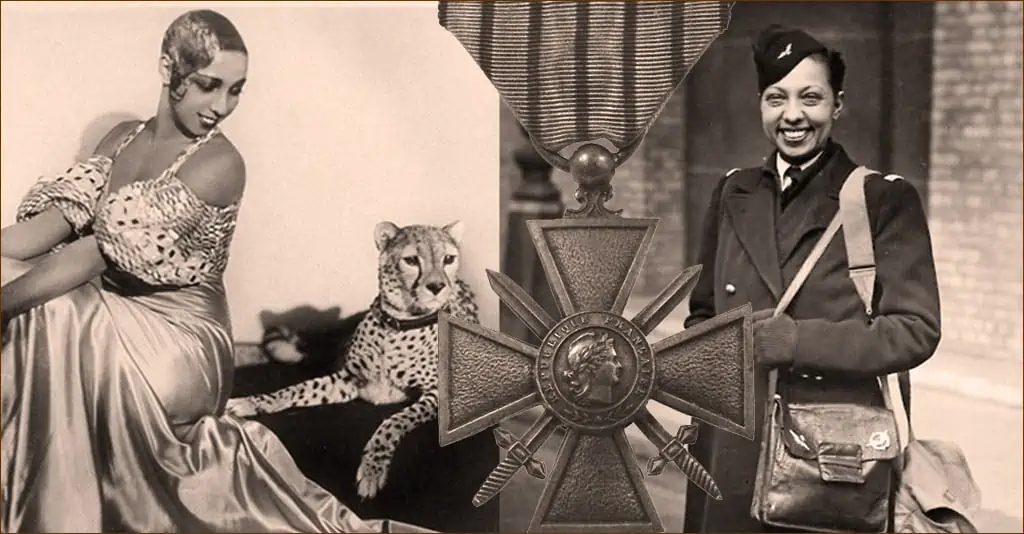

Josephine Baker took Paris by storm, dancing in nothing more than a G-string hung with fake bananas. She had a diamond-collared pet cheetah named Chiquita. Ernest Hemingway called her “the most sensational woman anybody ever saw.” But she was also a French war hero, World War II spy and a civil rights activist who raised 12 children she called her “Rainbow Tribe.”

Early Life

Freda Josephine McDonald was born in a St. Louis slum in 1906, when Jim Crow was the law of the land. At eight she was put to work as a maid for a white family who forbade her to look them in the eye or kiss their children. Three years later, she witnessed the East St. Louis race riot, thought by some to be the deadliest of the 20th century.

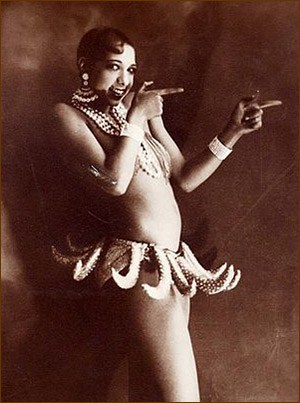

At 13, dancing for money on the corners of St. Louis, she was recruited to perform with an all-black dance company. She eventually made her way to New York City, becoming part of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1925 she debuted in Paris and earned star billing at the Folies-Bergère with a signature dance described as a combination Charleston and belly dance with some bumps and grinds thrown in for good measure. The City of Lights loved “La Baker,” and she loved it back.

She came home in 1936 to perform with the Ziegfeld Follies, hoping to capitalize on her overseas fame. Instead, met with audience hostility and racism, she quickly returned to France where, a year later, she applied for and was granted French citizenship.

Capt. Abtey and the French Resistance

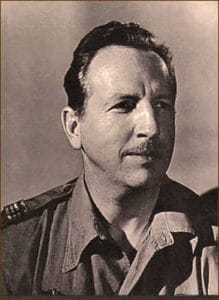

World War II was declared in 1939, filling Parisian streets with refugees fleeing the Germans. At the same time, Jacques Abtey, head of the French military intelligence service, was looking for undercover agents to work without pay for the French Resistance. He saw the perfect recruit in Josephine Baker — a world traveler, she rubbed elbows with people in high places and hated Nazis, who reminded her of the racists she left behind in America.

No sooner had he made his pitch when Baker replied, “France made me what I am. I will be forever grateful. The people of Paris have given me everything. I am ready, Captain, to give them my life. You can use me as you wish.” She was hired on the spot.

Spycraft “La Baker” Style

Dividing her time between Paris’ music halls and Red Cross shelters, Baker kept her ears open, collecting gossip and writing notes on the insides of her arms and palms of her hands. In the evenings, she attended parties and receptions all over Europe, all the while listening for intel on troop movements. Axis bigwigs, like Italy’s Benito Mussolini, adored her. In just one week, Baker passed important statistics and what is thought to have been a code book from the Italian embassy along to Abtey.

When Germany invaded France, she left the city for her 15th-century, 24-room chateau south of Paris, hiding refugees in the basement, along with people eager to help the Free French effort led by Charles de Gaulle. In 1940, Paris fell to Nazi Germany, and black and Jewish performers were banned from the city’s stages. So de Gaulle ordered Baker to Lisbon, a neutral city in Portugal. Traveling under the guise of going to South America to perform, her mission was to transport 52 pieces of classified intelligence. It was a daunting challenge until she and Abtey came up with the idea to transfer the data to Baker’s sheet music using invisible ink.

In Portugal, she partied at British, Belgian and French embassies, dancing, flirting and chatting up star-struck ambassadors. Then she returned to her hotel room and made notes, pinning them carefully to her bras and panties. She later recalled, “My notes would have been highly compromising had they been discovered, but who would dare search Josephine Baker to the skin?” She was right. In her elaborate clothes, wrapped in exotic furs, border patrols fawned over her, asking only for her autograph, as Abtey, posing as her assistant, slipped across borders with little notice.

From Portugal, they were sent to North Africa, where they were met by members of de Gaulle’s Free French movement. Their mission: establish a liaison with British intelligence and help set up a network providing Spanish Moroccan passports to eastern European Jews to help them escape to South America. As Baker toured Morocco, Spain and Portugal entertaining enthusiastic audiences, she fed information to the French Resistance.

“I’m Much Too Busy to Die”

Josephine Baker’s fame continued to grow. And what had started as a professional partnership with Abtey became an intimate five-year relationship. Her espionage work ended with an emergency hysterectomy after a miscarriage. Surgical complications sidelined her for almost a year, during which time Resistance members gathered in her private room to discuss German strategies and troop movements at her bedside.

With Baker out of the public eye for more than a year, international headlines in November of 1942 declared her dead, prompting Baker to contact one of the reporters and set him straight, saying, “there has been a slight error; I’m much too busy to die.”

La Baker Meets le Général

It wasn’t until 1943, at a benefit performance for the Free French forces in Algiers, that she finally met Charles de Gaulle, who presented her with a tiny gold Cross of Lorraine, symbol of the Free French. Though Baker, by then, had amassed more than a few beautiful jewels, this simple cross became her most prized possession. By war’s end, she would also be awarded the Croix de Guerre and Legion of Honor, France’s highest military honors.

Civil Rights Activist

After the war, Josephine Baker returned to America to find Jim Crow alive and well. In New York City, she was barred from hotels, unable to order even a cup of coffee because she was black. In 1951 she was refused service at the city’s famous Stork Club. When actress Grace Kelly witnessed the racist snub, she made it a point to approach Baker, then walk out, arms linked, in a show of support that sparked a lifelong friendship.

Touring the country to help fight segregation, she sat down on one Las Vegas stage, refusing to perform until the owner allowed black ticket holders to be seated. In a milestone that helped desegregate the casinos, her contract required every venue she played to seat ticket holders regardless of race. Back in Manhattan at the height of her tour, 100,000 people lined Harlem’s streets to honor the NAACP’s “Woman of the Year.”

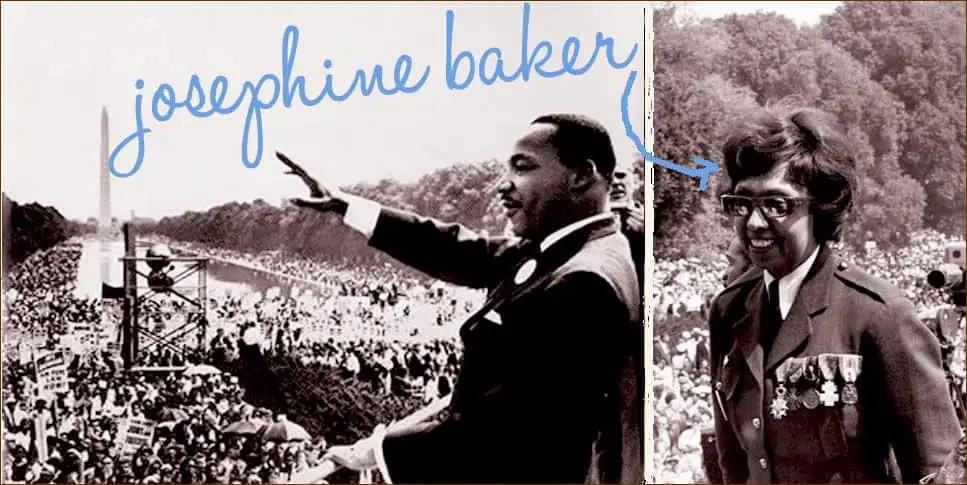

But the zenith of her civil rights activism was in 1963, when she stood alongside Martin Luther King, Jr., at his historic March on Washington. Dressed in her French military uniform, she was one of the few women to speak that day, declaring, as she looked out over the crowd, “salt and pepper — just what it should be.”

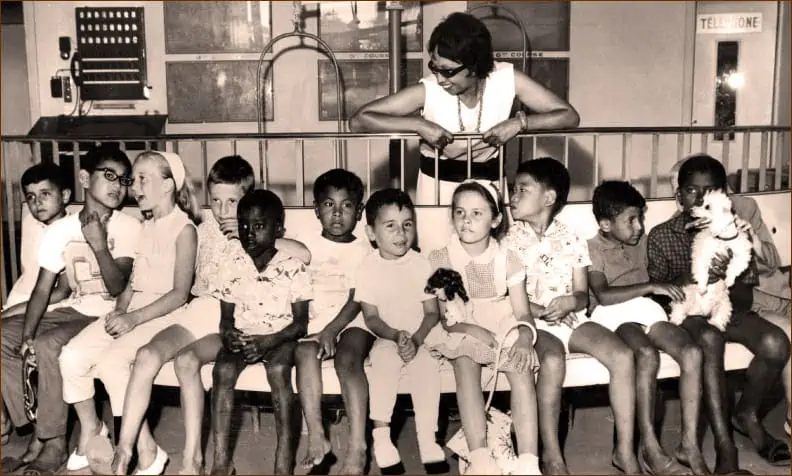

The “Rainbow Tribe”

Josephine Baker didn’t just advocate for racial equality in her professional life. In the 1950s, she embodied it by adopting 12 children from countries all over the world, including Japan, Algeria, Israel and Colombia, living with her “Rainbow Tribe” in her French chateau. To Baker, it was a “world village.”

But world villages are expensive. And by 1968, with Baker in financial trouble and creditors threatening to seize her home to settle her debts, Grace Kelly again reached out to lend support. When the creditors proved too much, Princess Grace arranged for Baker and her “Rainbow Tribe” to have a villa in Monaco.

The Last Days of “La Baker”

Despite Josephine Baker’s last years being fraught with financial difficulty, she never lost the resilience and pluck that served her so well as both a performer and freedom fighter.

In June of 1973, she staged a successful comeback performance at Carnegie Hall celebrating her Golden Jubilee marking 50 years in show business. Two years later, she was back in Paris for the first of a series of concerts commemorating the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut. She played to a sold-out house that included Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Liza Minelli and Diana Ross, earning a standing ovation and rave reviews. Just four days later, Josephine Baker died in her sleep at age 68 from a cerebral hemorrhage.

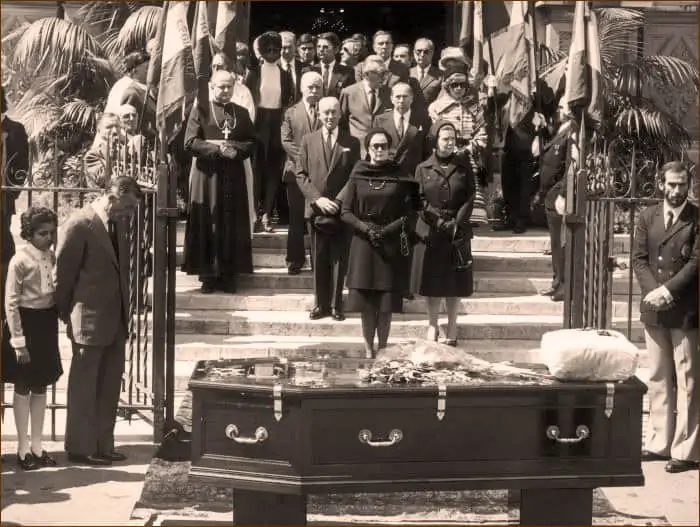

Her funeral was held in Paris, where more than 20,000 people crowded the streets to watch the funeral procession of the woman who had not only changed their world, but helped save it. The French government honored her with a 21-gun salute. From there, her body was taken to a church in Monte Carlo, her funeral cortege, led by Princess Grace, making its way to the Monaco Cemetery, a small cemetery overlooking the Mediterranean, where Josephine Baker was laid to rest