If you think women taking powerful older men to court under the banner of the #MeToo movement is something new, think again. A chance meeting between a young Madeline Pollard and a powerful politician in 1884 at the height of America’s Gilded Age set the stage for a sensational trial that helped change the way society thought about men, women and sex.

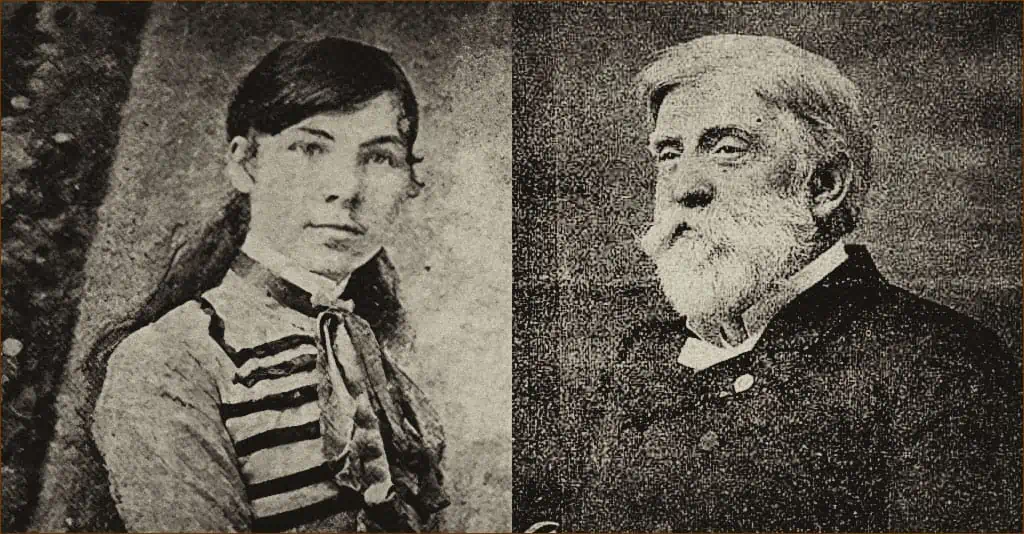

The “Silver-Tongued” Defendant

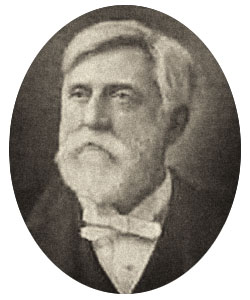

Colonel William Campbell Preston Breckinridge was a force to be reckoned with in Kentucky. The 47-year-old veteran of the Confederacy, cousin to America’s 14th vice-president and five-term congressman, was a twice-married, middle-aged father of five with a silver tongue and aspirations to the presidency. The New York Herald described “his imposing appearance, his dignified, almost fatherly, bearing, his courtly manners, his earnest, warm-hearted friendliness, his sparkling appreciative eyes, his ready intelligence, broad cultivation and quick, harmless wit [making] him a universal favorite.”

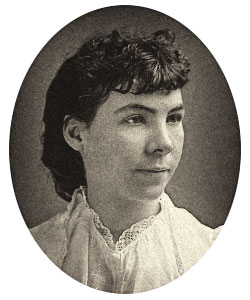

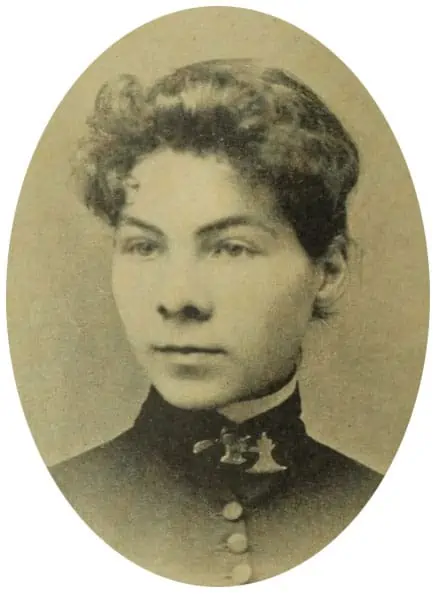

The “Mouse-Like” Plaintiff

Kentucky-born Madeline Pollard was a 17-year-old student described by classmates as plain, quiet, unobtrusive and “mouse-like.” The daughter of a saddler whose shop also sold newspapers and highbrow magazines like Harper’s, she was an avid reader and excellent student who mastered Latin, memorized Shakespeare and dreamed of a literary career.

When her father’s sudden death left her mother and six siblings in dire financial straits, Pollard was sent to live with a succession of aunts. A cousin remembered her as a “remarkably bright girl” who spent the better part of her teens trying unsuccessfully to find a relative to pay for her continued education at a time when college was considered a luxury, especially for a girl. Watching her mother struggle to keep herself afloat by mortgaging what little furniture they had in order to feed her younger children, she realized the only way for a woman of her time to find financial security was through a man.

A Faustian Bargain

As disagreeable as it seemed, she entered into an agreement with a local farmer to fund her schooling in return for her promise to marry or repay him after graduation. But not long after enrolling in Cincinnati’s Wesleyan College, one of the most prestigious girls’ schools in the country, where she saw herself surrounded by a cultured, literary crowd, she had a change of heart and was looking for a way out.

Breckinridge and Pollard met in April of 1884 when the Colonel was on a train heading home to Lexington and Pollard was traveling to see an ailing sister. Recognizing Breckinridge immediately (he had been her late father’s longtime political idol), she engaged him in a brief conversation. Not long afterward, she followed their chance meeting with a letter seeking his professional advice on how best to extricate herself from the agreement she had made.

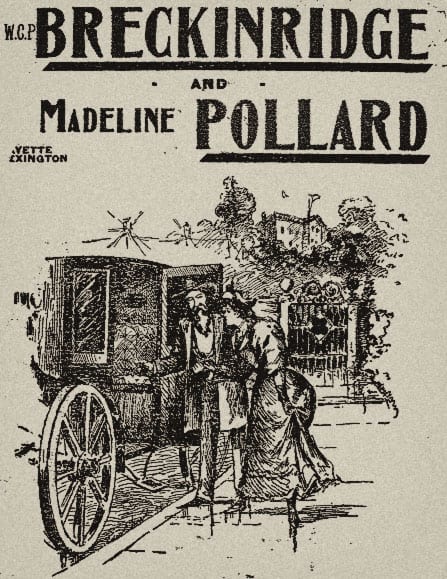

Closed Carriage Confidential

Breckinridge was only too happy to oblige a constituent, traveling to Pollard’s school to consult with her in person. But because it was such a personal matter, he suggested a more “confidential” discussion, well away from the eyes and ears of chaperones. And so it was that the two left campus that night in a closed carriage. Now while that might not seem like a big deal to us, Victorian social morés dictated that no decent woman ever be alone in a closed carriage with a man who was wasn’t a close relative. Breckinridge later convinced Pollard to meet him in Lexington where, two days later, after he had dined quietly with his wife, he met and seduced Pollard at a secret location.

Two Pregnancies and Promises to Marry

As so often happens, one thing led to another and Madeline Pollard became the Colonel’s mistress. It was at his suggestion she transferred to the Sayre Female Institute in Lexington to be closer to him. Over the next three years, Breckinridge paid her tuition and board at Sayre, and the two met at least 50 times.

Pollard also became pregnant twice during that period. Both times, the Colonel sent her to lying-in homes — charities that took in unwed mothers to keep them out of the public eye. And both times, Pollard gave her babies up to what were known as infant asylums, where both children died. She agreed to relinquish them when Breckinridge insisted he couldn’t risk having their paternity traced to him.

In 1887, Breckinridge moved Pollard to Washington, D.C., where he got her a job with the Department of Agriculture and Census Bureau, and the two continued to meet several times a week. Whenever they saw acquaintances, the Colonel introduced Pollard as his fiancée or his daughter. In fact, Pollard once told a friend he “was as careful of me and my reputation as if I had been his daughter.”

Breckinridge had always assured Pollard he would marry her if only he were free to do so. Following the death of his second wife in 1892, Breckinridge proposed they marry, but only after a suitable period of mourning — a promise he later denied, saying, “It was not a promise. I was in a state of mind that was excited and I said, ‘Yes, I’ll marry you,’ and I went right on talking.”

That same year, Pollard became pregnant for a third time; but this time the congressman swore he would accept the child as his and they would marry. They even began debating names for the new baby and set a wedding date of May 31, 1893.

Betrayal and Breach of Promise

What Madeline Pollard didn’t know was that Breckinridge was also secretly courting Louise Scott Wing, a socially prominent Washington, D.C., widow who happened to be his distant cousin. On April 29, a month before he was to take Pollard as his wife, Breckinridge and Wing were secretly married in a pastor’s home in the presence of just two witnesses. Several weeks later, Pollard learned of the betrayal and, on May 24, suffered a miscarriage. Finally realizing Breckinridge had taken advantage of her, stringing her along for a decade, she sued him for $50,000 (or $1,140,889.00 today) for breach of promise in what would become one of the biggest political sex scandals of the Gilded Age.

Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, in an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, explained the ramifications of such an act. “Breach of promise suits were not uncommon. … Marriage was a woman’s primary career in those days; aging out of what was considered a desirable marrying age posed real financial hardships. Those suits protected the reputation of respectable women who were wronged. But in Pollard’s case, she admitted to being a ‘fallen’ woman at a time when ‘fallen’ women were social pariahs — she couldn’t get a respectable job, live in a respectable home and could never expect to make a respectable marriage after Breckinridge reneged on his promise to marry her.”

Politics, Sex and the Juicy Details

The Madeline Pollard case was tried in the nation’s capital in a trial lasting 28 days. Lines formed outside the courtroom; upholding the tightly-laced Victorian morals of the day, women were barred from the courtroom lest they hear the lurid testimony. But, for more than a month, people all across America couldn’t get enough of the salacious details.

The Colonel’s team claimed Pollard was “utterly depraved where morality is concerned” and, therefore, fair game. They painted her as someone an influential congressman would never associate with — an experienced “prostitute” who deliberately lured him into a liaison. He went so far as denying paternity or even having any knowledge of her children — a tactic which blew up in his face. But most of their evidence was hearsay and, in the words of the judge, “too filthy and obscene” to be heard.

Pollard countered with her own version of the affair as covered by The New York World, claiming she was a naive young girl betrayed who, “with this man alone have I ever been guilty of a single impure thought or act.” Dressed from head to toe in black and accompanied by a nun, Pollard made an impressive witness, never wavering under vicious cross examination by the defense, even fainting at one point as she recounted the death of her second child.

The trial revealed a treasure trove of secrets. Pollard and Breckinridge had secretly conducted an affair for the last decade. He had seduced the young college student, promised marriage and then reneged. Then, following his second wife’s death, Breckinridge, widowed for less than a year, secretly wed his distant cousin.

Salacious He-Said-She-Said Headlines

The press went crazy. Local reporters dug into the juicy story, investigators scoured Kentucky, and lawyers tracked down anyone who claimed to have known Pollard. Breckinridge even employed a female spy to ferret out “just exactly what kind of woman this is.” Two competing narratives emerged: either she was a knowing, social-climbing adventuress actively pursuing her goals, or the innocent, seduced schoolgirl who was the passive victim of the will of a powerful man.

The trial was a roller coaster of he-said-she-said allegations. But, surprisingly, the public almost universally condemned Breckinridge’s behavior and supported Pollard, as was reflected by these national headlines: “Col. Breckinridge Continues His Revolting Tale. Does Not Attempt to Defend His Action.” “Lived a Life of Faithlessness, Duplicity and Hypocrisy, Steeped in Original Sin.” “Filth. Breckinridge’s Lawyers Uncork a Lot of It.” And “Willie Was Much Worse Than Maddie.”

In closing arguments, Breckinridge’s attorneys cast Pollard as a “self-acknowledged prostitute” to no avail. The judge then charged the all-male jury, as described by yet another sensational headline: “Judge Wilson Asks That the Defendant Be Held Up As a Horrible Example and the Jury Impale Him.”

Final Verdict

The jury did just that. They returned after less than 90 minutes, finding in Pollard’s favor and awarding her $15,000 (which, in 1894, was three times the Congressman’s annual salary). In less than an hour and a half, Madeline Pollard won a moral victory while the Colonel suddenly became symbolic of everything women hated about men’s sexual behavior. He promptly filed for an appeal and a new trial, but was denied on both fronts.

Breckinridge’s return to Kentucky to campaign for reelection couldn’t have come at a worse time. He was firmly denounced by newspapers, civic associations and religious groups as a “rapist,” a “lust fiend,” and a “wild beast in search of prey.” But most importantly, the trial galvanized Kentucky’s suffrage movement.

Kentucky Women Rise Up

Suddenly, as one local paper wrote, “women who never took the slightest interest in politics have become active politicians.” Women in the thousands attended protests; resolutions were adopted calling for Breckinridge’s defeat. Businesses that supported him were boycotted and parents refused to allow the sons of his supporters to court their daughters. Soon after Pollard’s victory, a letter signed “Many Women” ran on the front page of The Kentucky Leader, urging Democratic Party leaders to withdraw their support of Breckinridge in his upcoming reelection bid. “Let him sink into the oblivion of his guilt. Let his voice be silent.”

The Colonel cried, groveled and begged his constituents’ forgiveness, saying, “I have sinned and I repent in sackcloth and ashes.” When the final ballots were counted, he had lost — but only by 255 votes. He never held public office again, the women of Kentucky taking credit for his defeat.

Aftermath

Breckinridge quietly returned to his law office and began to work for his son at the Lexington Morning Herald. His third wife suffered a nervous breakdown. And in 1904, Colonel William C. P. Breckinridge died of complications from a stroke, a mentally, physically, and financially broken man. It was reported he never paid a cent of the settlement awarded to Pollard. He lies in The Lexington Cemetery, his grave marker reading “He devoted all his great endowments with rare unselfishness to the service of his country and to his fellow men.”

As for Madeline Pollard, she picked herself up and went to Europe. In the Spring of 1897, the Washington Post reported her whereabouts in London, where she was “studying with the view of engaging in literary work.” It was there she met a wealthy Irish widow named Violet Hassard, in whose company she traveled the world. Hassard and Pollard, who would become lifelong friends, appear in the 1901 English census in Oxford, Pollard citing her occupation as a “writer of fiction/author.”

Madeleine Pollard died in December of 1945 at the age of 79 at The Cottage Hospital in Barnstaple, Devon, England, leaving a small estate (less than $600 US dollars today) to her “beloved friend” Violet Hassard, with whom she had lived a life of study, travel and adventure since 1900. Her place of burial is unknown.

Legacy of Pollard v. Breckinridge

Although Madeline Pollard never saw a penny of her $15,000 jury award, she succeeded in publicly challenging the Victorian double standard for sexual conduct that viciously judged women’s sexuality while celebrating men’s with the proverbial wink and a nod. A case like hers had never been tried before. But, as it turned out, her timing couldn’t have been better.

In 1893, America was rocked by “The Panic of 1893” as businesses closed and unemployment skyrocketed. Women increasingly sought employment as families struggled to survive on one income, with roughly 75% of those women being single. Society began to question the long-held idea that “good” women stayed home, while women who went out into the public world were fair game. It followed that men’s behavior began to be questioned in that new light.

Women started speaking up for Pollard — she was a younger woman; he was older; he was married; and he was in a clear position of power over her. Over the course of a month, the Colonel emerged as a sexual predator instead of Pollard being demonized as the “fallen” woman trying to corrupt a good husband. By the time the verdict was rendered, both sexes approved the verdict in Pollard’s favor by a wide margin.

Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, whose years of exhaustive, meticulous research included Breckinridge family papers and newspapers from the era, wrote, “the trial’s media coverage provided Victorian America with a new kind of sex education and created an opening for reformers ‘who for decades had been pushing without much success the idea of a single standard of morality for both men and women.’ And as chastity became central to the definition of a respectable woman in the 19th century, women found it was their sexual conduct, not the actions of men, that was really on trial.”

Today, we’ve seen hundreds of powerful men accused of sexual offenses since the emergence of the #MeToo movement. Many of them lost jobs or resigned their positions as a result. But with the exception of high-profile celebrities like Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, R. Kelly and U.S. gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, very few have faced serious legal consequences. Sometimes the more things change, the more they stay the same.

This is true justice at it it’s best.

Few have more admiration than I for those speaking truth to power.

Father of three remarkable daughters.

pat Weber

Respect her