If a picture is worth 1,000 words, the photo of a New York City luncheon (above) hosted by famed radio DJ and promoter Alan Freed speaks volumes. He’s surrounded by 57 songwriters, music executives and producers, all of them male. Except one — Rose Marie McCoy.

As soul and R&B singer Maxine Brown recalled, McCoy “knew how to hang in there with the big boys.” At a time when women, much less Black women, didn’t have a place at the table, McCoy made a place for herself. She wrote or collaborated on over 800 songs over 60 years for some of the 20th century’s best-known artists. So why have so few people heard of her?

It took a 2009 radio documentary heard on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered – Lady Writes the Blues: The Life of Rose McCoy, to remind listeners of just who Rose Marie McCoy was and why she matters.

Arkansas Blues Delta

Rose Marie McCoy was born in a drafty tin-roofed shack in Oneida, AR, in 1922. In the heart of the Arkansas Blues Delta, McCoy described it as “the kind of place you pass through without even knowing you’re passing through it.” She had to travel 18 miles from home to hear the blues, standing outside a club called the Hole in the Wall where blues artists were paid $3 a night plus all the whiskey they could drink.

Her grandparents lived in Helena, about 16 miles away. McCoy’s parents sent her there to attend Eliza Miller High School, a school for Black students, where she thrived. She was voted Most Friendly and Queen of the Football Team; took part in school shows and saw Black jazz bands perform. But it wasn’t until she heard the Sweethearts of Rhythm, the first racially integrated all-female jazz band, perform that she knew what she wanted. She wanted to get enough money to raise her family out of poverty. When her brother-in-law told her, “You know, when you’re a professional singer, they pay you,” she knew what she had to do.

Following a Teenage Dream

So, in 1942, at age 19, Rose Marie McCoy left home for New York City to chase a dream with $6 in her pocket and a remarkable gift: she knew she could tell stories with her songs.

She settled in Harlem, ironing shirts at Chinese laundries where they paid her by the piece and taking weekend gigs at small clubs. On a trip back home in 1943, she married former sweetheart James McCoy – a marriage that would last 57 years until his death in 2000. While he worked for Ford Motor Company, she traveled the Chitlin’ Circuit, opening for top performers like Pigmeat Markham, Dinah Washington and Moms Mabley.

In her spare time, she wrote songs. Her first song to appear on a record was “After All,” recorded in 1946 by the Dixieaires. But when she saw the amount of her royalty check, she decided to stick to her singing career. Ten years after moving to New York City, she snagged an audition for Wheeler Records, a short-lived blues label. Capitalizing on the growing popularity of Black music, they recorded two of her songs. But they weren’t just sold on her voice; they especially liked two of her songs, “Cheatin’ Blues” and “Georgie Boy Blues.” Publishers soon began to seek her out, with one of her first songs reaching #3 on Billboard’s Rhythm & Blues 1953 charts.

First Award-Winning Hit

Rose Marie McCoy got her first real taste of success that same year from a duet with blues belter Big Maybelle. Written as a put-down, “dozens” style, call-and-response song, Maybelle would sing a line and McCoy would come back with an insult. Harkening back to a tradition of African American insult dueling and social interaction, it became Big Maybelle’s first hit and earned McCoy the first of seven Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) awards. Her career as a songwriter was taking off.

In 1953, she also teamed up with her first partner, Charles Singleton, who penned the lyrics to “Strangers in the Night,” made famous by Frank Sinatra. They met every morning at 6 AM in a booth at a restaurant called Beefsteak Charlie’s, where they’d order 30¢ glasses of wine and start writing. It was located around the corner from the Brill Building, the hallowed music temple just north of Times Square. A 10-story hit factory filled with songwriters, producers and music publishers, it was home to music by Carole King, Paul Simon, Neil Sedaka, Neil Diamond and Burt Bacharach.

Lyrics on Napkins

Sometimes scribbling lyrics on napkins and paper bags, they could sell songs they’d written that morning by the afternoon. As Maxine Brown remembered, “the place was hoppin’. A lot of the songs you heard back in the old days were sold right out of that restaurant.”

Back when most performers relied on professional writers for their hits, writing came naturally to McCoy. “I’d get started, Charlie would play chords, and I’d get the melody in my head from his chord,” she recalled. “I just thought anybody could do it. It’s like you talk. And if you do that, it just sort of writes itself.”

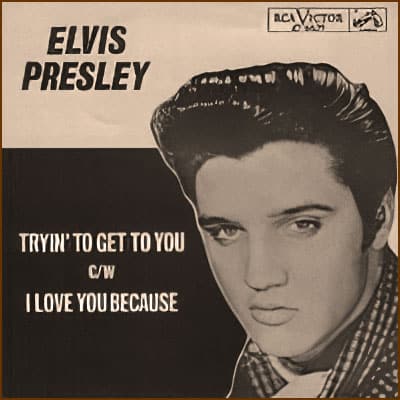

McCoy and Singleton wrote a song called “Trying to Get to You” for a Black group from Washington, DC, called The Eagles in 1954. But a skinny, unknown kid with a greasy pompadour heard their version in a Memphis record store and decided to record her song on his debut album for RCA Records the next year. McCoy later remembered, “He wasn’t a big star at that point, and we thought he was terrible because we thought he couldn’t sing,” before adding, “thank God for Elvis.”

Songwriter for the Stars

Presley’s album ruled Billboard’s pop chart for 10 solid weeks. And while the single never made it to #1, he included it on follow-up albums and performed it in live concerts. More than 30 artists went on to record it, including Roy Orbison and The Teen Kings, Ricky Nelson, Eric Burdon of The Animals, Johnny Rivers, Faith Hill and many others.

In 1955, popular DJ and promoter Alan Freed popularized the term “rock ‘n’ roll” on his mainstream radio show. It was a time when live music shows and dances were segregated and white teenagers wanted to hear Black performers. “To have them in the same building, owners put a rope down the middle of the floor – the whites on one side and the Blacks on the other side,” said McCoy. “Everyone enjoyed the music; you just didn’t cross over the rope. They just wanted to hear what you had. If they liked it, they didn’t care if you was black or white. We all thought it was the blues; but they called it rock ‘n’ roll. I still don’t know the difference.” That quote became the title of McCoy’s biography, Thought We Were Writing the Blues: But They Called It Rock & Roll, by author and friend Arlene Corsano.

Ike and Tina Turner

One of Rose Marie McCoy’s biggest hits came in 1961 with “I Think It’s Gonna Work Out Fine” recorded by a little-known, up-and-coming duo, Ike and Tina Turner. They were awarded a Gold Record and received a Grammy nomination. McCoy, by now, had bought herself a house in Teaneck, NJ, and a green Cadillac. And she had her very own office in the fabled Brill Building.

Over her long career, she was offered jobs as a staff songwriter with Motown, Stax, Atlantic and other record labels, but turned them all down. She wanted to maintain her independence and keep control of her music. As Al Bell, one-time head of Stax and Motown put it,” She realized her power was in the pen. And she was one of those rare persons that wanted to be free to write her own songs and do what she wanted to do.”

In 1964, things were about to change. A mop-top group called The Beatles had five of their 10 biggest songs on the Billboard charts. One was a cover of “Twist and Shout” penned by songwriter Bert Berns and based on the Mexican folk tune “La Bamba, but the rest were their own songs. Writers like Bob Dylan began to emerge and perform their own songs — writers who, as Al Bell recalled, “got recognition as singers and great writers. I saw our industry, for want of a better way to say it, kick the songwriter to the curb. And Rose Marie McCoy was just another songwriter.”

Coca-Cola Jingles

As a result, many of the Brill Building writers had to find new ways to earn a living. Some, like Carole King and Neil Diamond, launched successful singing careers; some became producers; others left the music business altogether. But not McCoy, who kept working. In the 1970s she wrote and produced a jazz album with Sarah Vaughan; wrote Coca-Cola jingles performed by Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles; branched out into country music in 2013; and had formed her own music publishing firm, McCoy Music.

In 1986 she was still living in Teaneck, NJ, in a house packed with boxes of reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes and old records. And she was still writing, sometimes waking up during the night with a new song in her head. “I had that happen the night before last,” she said in the 2009 NPR interview. “I should’ve got up and wrote it down. But what’s the use? I’m retired now.”

Rose Marie McCoy died of pneumonia at the age of 92 in January 2015 in Urbana, IL, where she had moved to join a niece.

She grew up at a time when racism was the law of the land. She was marginalized because of her gender. And she knew what it was like to live in poverty. But she broke into the mostly white, male-dominated music business to become the first Black woman to make it big as a songwriter, with an amazing career that lasted for 60 years.

Superstar Songwriter

Rose Marie McCoy’s music spanned the genres of R&B, jazz, gospel, rock and roll and, late in her life, country. More than 300 artists have recorded her songs; their names read like a Who’s Who of American music: Nat King Cole, Elvis Presley, Sarah Vaughan, Big Maybelle, James Brown, Patti Page, Eartha Kitt, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Bette Midler, Ike and Tina Turner, Mickey & Sylvia, Linda Ronstadt, James Taylor, The Spencer Davis Group, Manfred Mann, Diana Ross & the Supremes and many more.

Honored by Community Works NYC in a 2008 exhibition and concert series titled “Ladies Singing the Blues,” she received a five-minute standing ovation during the awards ceremony at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for her contribution to music, where it was only fitting that “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine” played as she was escorted to the stage. She was honored for contributions to black culture and entertainment by the New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2008, and the Arkansas Jazz Hall of Fame in 2018.

And whenever Rose Marie McCoy was asked which of her many songs was her favorite, her reply was always the same: “The last one I heard playing on the radio.”

I wish that I could have meet her, I love older black women, they’re so sweet 😋!

Phenomenal, Phenomenal, Fantastic