Margaret Bourke-White, who entered college in the 1920s with the idea of becoming a Herpetologist, could have made a name for herself handling snakes. Instead, she picked up a camera and went on to become a groundbreaking female photojournalist, giving us some of the most iconic images of the 20th century.

She watched history unfold, taking Americans with her through the lens of her camera. Always possessed of an adventurous spirit and an unquenchable curiosity, she once said, “Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open.”

Bourke-White was born in 1904 in the Bronx, New York, but grew up in Bound Brook, New Jersey. After graduating from Plainfield High School, she attended several universities in pursuit of a degree in Herpetology (the study of reptiles) before receiving her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1927 from Cornell University.

An all-consuming hobby

She always considered photography a hobby, having been exposed to seeing life through a lens as a young girl by her photography-enthusiast father. Her formal photographic education came from courses at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York where, along with technical training, design and art theory, students were urged to find and follow their own creative vision. Using a $20 second-hand camera with a broken lens, Bourke-White started taking pictures in college. After that, as she once said, “I never really felt a whole person again unless I was planning pictures or taking them.”

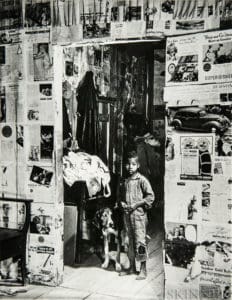

Bourke-White moved from New York to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1927, where she opened her own studio, specializing in architectural and industrial photography. She sought to document the might of American capitalism by showing the effects of the heartland’s fiery steel mills and gritty factories on its people and the landscape, using a new style of magnesium flare whose sudden flashes of bright light captured incredible detail in stark black and white photos.

LIFE Magazine

Her photos eventually caught the eye of publisher Henry Luce who, in 1929, hired her for his newest publication, Fortune magazine. Seven years later, he offered Bourke-White another job — this time as the first female photographer for the new Life magazine. One of the first four photographers hired, her 1936 shot of Fort Peck Dam was reproduced on that magazine’s inaugural cover.

For decades thereafter, Bourke-White traveled the world — more than a million miles, working in 45 countries — photographing the major events of her time and racking up a mind-boggling list of “firsts” and “onlys” along the way.

She was the first accredited Western photographer to document Soviet industry during the Kremlin’s series of five-year economic plans that began in the 1920s.

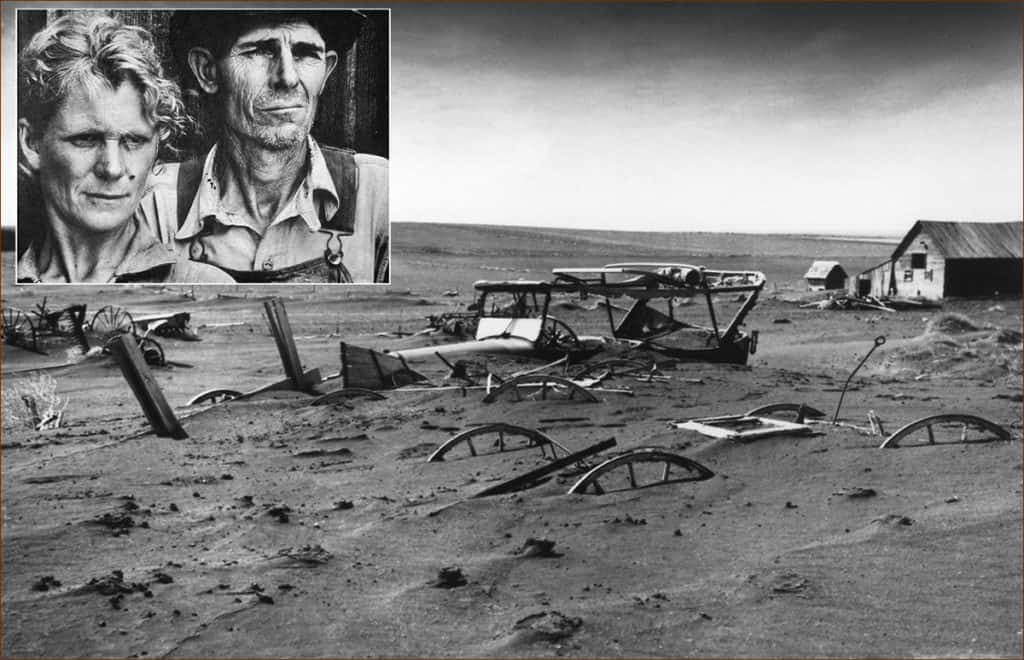

Along with colleagues Arthur Rosenstein, Dorothea Lange and others, she spent a good part of the 1930s photographing the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl.

When World War II broke out, Bourke-White was the first woman correspondent to work in combat zones and the first female photographer, working for both Life Magazine and the U.S. Air Force, to witness Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Kremlin.

While attached to General Patton’s army in Germany, she gave Americans a shocking look at the human face of war by documenting the horrors of Buchenwald concentration camp after its liberation in 1945.

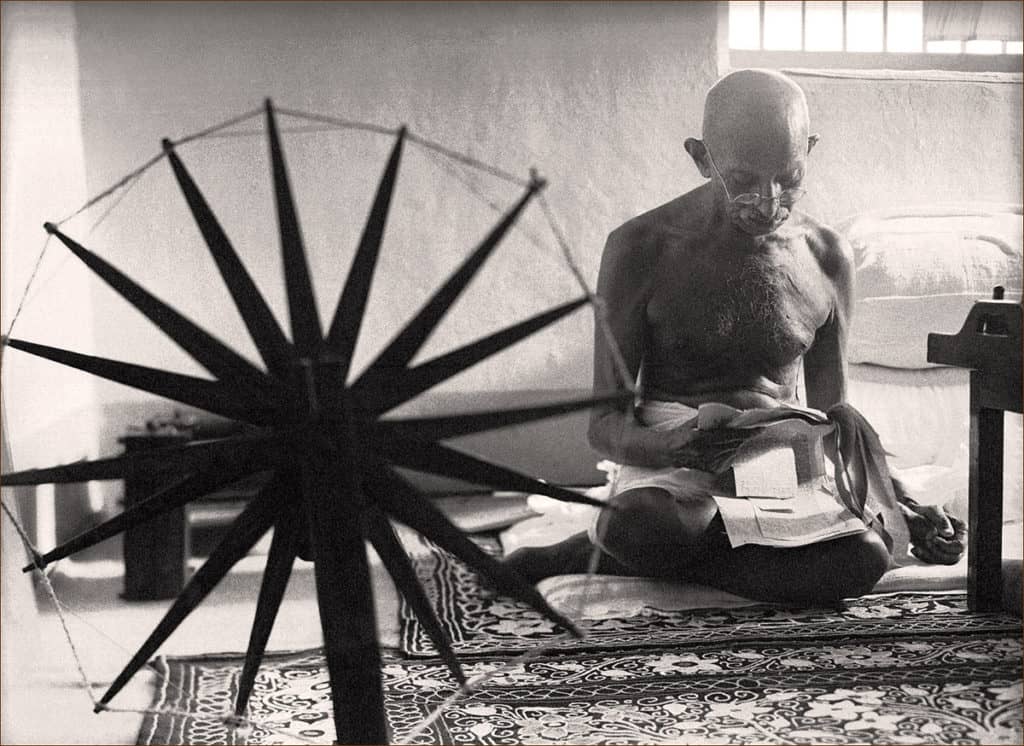

A year later, in 1946, she covered Mahatma Gandhi’s fight for Indian independence, taking the iconic photo of him at his spinning wheel two years before his assassination.

Bourke-White also covered the Korean War, traveling with South Korean troops and giving her what she once called her best photo ever – a returning soldier meeting his mother, who thought he had died months earlier.

Margaret Bourke-White returned to America after the war and continued her photography, this time focusing her work on humanitarian issues. Along with other artists, she formed the American Artists’ Congress, advocating for state and public support of the arts and against the discrimination of African-American artists.

Civil Rights struggle

Throughout her career, Bourke-White’s commitment to social justice was no secret. In fact, the FBI had been building a file on her since the 1930s. And in the McCarthy era of the 1950s, she was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee because of her involvement with groups fighting for civil and political rights.

But in 1952, at age 48, Margaret Bourke-White — having earned the nickname “Maggie the Indestructible” after returning from covering wars and shooting combat zones unscathed — began to show symptoms of what was diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease. Increasing stiffness in her hands interfered with her ability to use a camera, and encroaching immobility forced her to slow down.

After a long career behind the camera, perhaps proving the saying “the camera never blinks,” she invited her friend and fellow photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt to document her treatments and physical therapy, taking the disease out of the shadows and sharing her fight with America.

Autobiography

She would spend the next eight years writing her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, which was published in 1963. Bourke-White died in 1971 at Stamford Hospital in Connecticut, at the age of 67. Cremated at her request, the location and disposition of her ashes is unknown.

Over the course of her remarkable life, Margaret Bourke-White received many awards and honorary degrees for her work including honorary doctorates from Rutgers University in 1948 and the University of Michigan in 1951. She published twelve books, was given the U.S. Camera Achievement Award in 1963 and the American Society of Magazine Photographers’ Honor Roll Award in 1964. And in 1997, Bourke-White was designated a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project .

In a time when women were still largely defined by their husbands and praised for the quality of their housekeeping skills, Bourke-White pushed the boundaries of being female and tossed traditional roles out the window. She did it her way, living with a married man, having affairs, and putting career above a husband and children. Her combination of professional skill and socially responsible philosophy made her one of America’s 100 most influential women of the 20th century.

I am creating a one hour video interview of Victor F Erdelac who was a gunner on 50 missions of B17’s in WWII. Victor recalled a mission that Margaret Bourne-White was onboard as a staff photographer for life magazine on June 6, 1943. I am trying to find the photos that were published in Life Magazine and a good picture of Margaret to fade into the video as Victor is recalling the mission. Victor is one of the original members of the 301 Bomber Group and will be turning 100 years old on July 5. We are trying to create a video that will a proper tribute to His service in the big war. I can be reached at 224-717-2807 if you have questions. Thank You