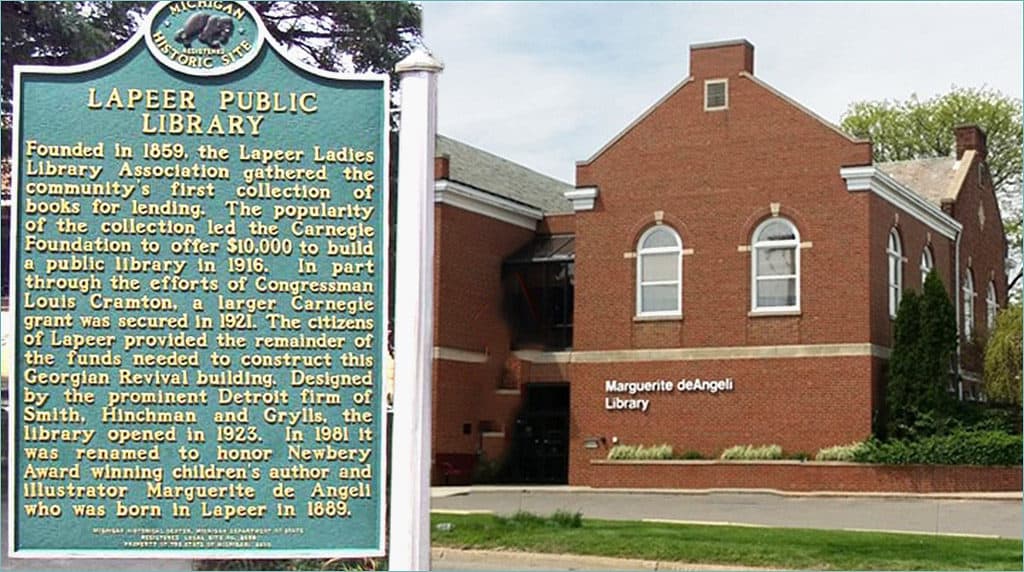

Marguerite de Angeli, this Wednesday’s Woman, was born in a small town where “we’d had no library.” But in her later years, as the beloved best-selling author and illustrator of books that influenced the values of generations of children, she returned to that same town to read her books to children at the library named in her honor.

During her long publishing career, de Angeli excelled at depicting the traditions and cultural diversity of people often overlooked in children’s literature of the time — a Great Depression family, African-American children experiencing racism, Polish miners whose dreams took them beyond Pennsylvania’s coal mines, the disabled, 19th-century Quaker abolitionists, native Americans and immigrants.

De Angeli (1889-1987) was born in Lapeer, Michigan, one of six children. Her father drew crayon and pastel portraits when he wasn’t working as the town photographer. But, finding it hard to support a large family in a small town, he eventually took a job with Kodak and was transferred to Philadelphia.

Collingswood, NJ

De Angeli spent most of her youth in Philadelphia, a city that would be the setting for many of her books. She married violinist John Dailey de Angeli in 1910 and, four years later, she and her husband and their growing family settled in Collingswood, NJ.

Though the family — Marguerite, John, and their six children — moved often, they never went very far, choosing homes in Jenkintown, Manoa, Germantown and Center City Philadelphia, as well as a summer cabin along Toms River, NJ.

De Angeli began her serious study of drawing in 1921, when Collingswood neighbor Maurice Bower, an illustrator whose equine art was featured on the covers of the Saturday Evening Post in the 1930s, took her under his wing. With a studio set up in the family dining room, and juggling the demands of five children (one, a daughter, had died suddenly in 1915) and her household duties, de Angeli worked whenever she found the chance.

Within a year, her illustrations were featured in popular magazines like The Country Gentleman, Ladies’ Home Journal and The American Girl. Throughout her long career, she worked in various media, including charcoal, pen and ink, oils and watercolors. Having written and illustrated 28 books of her own, she illustrated more than three dozen books and magazine pieces for other authors.

Everyone deserves respect

The belief and underlying message of her published work was the simple idea that everyone deserved respect. Carefully drawn characters and meticulous research into the time and place in which their stories unfolded were hallmarks of de Angeli’s books.

Her first book, Ted and Nina Go to the Grocery Store and based on the adventures of her own children, was published in 1935.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#663300″ class=”” size=””]”If thou followeth a wall far enough, there must be a door in it.”[/perfectpullquote]Her 1946 book, Bright April, shined a light on racism as it told the story of a young black girl growing up in Germantown, just outside Philadelphia. Her 1936 book Henner’s Lydia, the story of a young Amish farm girl, put the Amish on the map as a tourist destination when it tapped into the American sense of a simpler way of life. Four years later, when the PA Turnpike opened, the book’s Lancaster County setting became an easy drive from Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New York City. And her 1954 Book of Mother Goose and Nursery Rhymes, with its 387 rhymes and 260 illustrations, is a classic in children’s literature.

Literary Awards

Her awards include the Caldecott Medal to the artist of the most distinguished American children’s picture book in 1945 and 1955; the Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American children’s literature in 1959; the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award, for books worthy of shelf space alongside Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1961; and the 1968 Regina Medal from the Catholic Library Association for a lifetime contribution to children’s literature.

Marguerite Lofft de Angeli’s last work, Friendship and Other Poems, was published in 1981 when she was 91 years old. She continued to write until her death in Philadelphia in 1987, at the age of 98.

The author who, in her autobiography, wrote, “we’d had no library in Lapeer,” now has a library named in her honor in her hometown. And, closer to home, the Free Library of Philadelphia hosts an annual birthday celebration for their adopted daughter.

She is buried at Saint Paul’s Lutheran Cemetery in Montgomery County, PA, beneath a simple headstone that reads “Everybody’s Grandmother.”

I, too, read the books by Margaurite DeAngeli as a child in grade school (early 50’s). I was drawn to the characters and their backgrounds which felt similar to my own. “Bright April” was a favorite, as well as “Up the Hill” and “Henner’s Lydia.” I was able to snag several of DeAngeli’s books when the library I was working in was discarding old books. It was a treat to reread my childhood favorites. Margaurite DeAngeli was definitely ahead of her time!

De Angeli’s 1946 book Bright Angel was one of my favorite books in elementary school in the early 1950s. I came across it again when my grandchildren’s school library was culling its shelves. I grabbed it and now, many years later, I am reading it.

Google brought me to your site…and info on the site of the library that is named after her. She was an extraordinary woman who chose to write about the underrepresented. Apparently, it took six years for Bright April to be published. I’d like to find out more about that…and more about how she chose her subject matter. One of these days, perhaps I’ll talk to the archivist at the library.

She was ahead of her time.