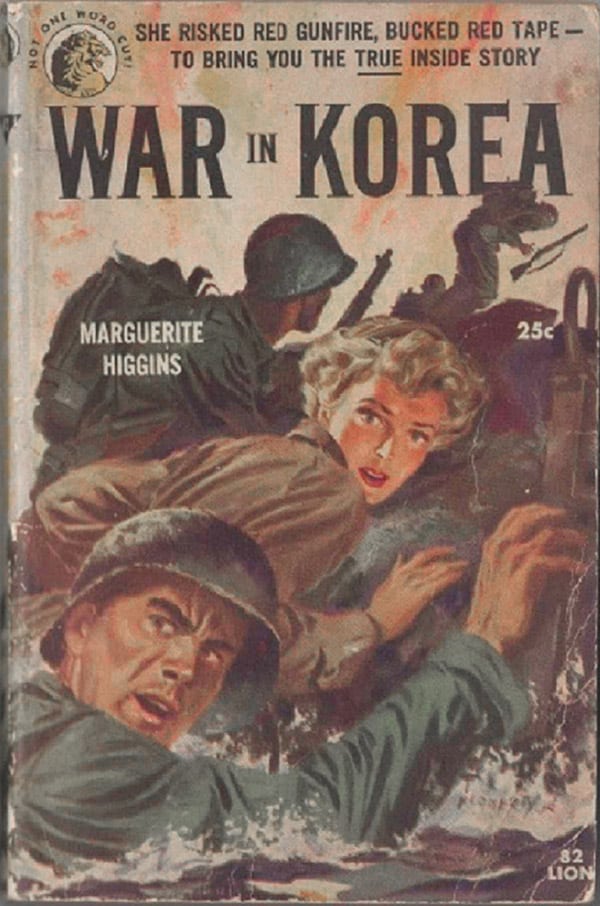

Marguerite “Maggie” Higgins wasn’t America’s first female war correspondent. Legendary journalist and novelist Martha Gellhorn (who was also Ernest Hemingway’s third wife) had covered conflicts all over the world in her 60-year career. But Higgins was the first to win the coveted Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1951 with her front-line coverage of the Korean War.

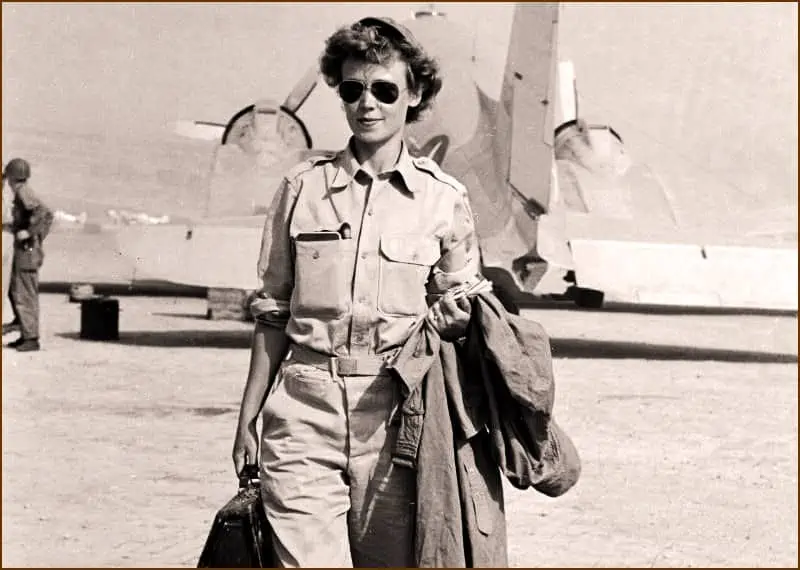

She stood at the front line in two traditionally male-dominated fields — journalism and warfare — and never backed down, despite having her sense of belonging challenged at every turn because of her sex. Her tenacity, her ambition and what some recalled as her “almost pathological” competitive drive to get a story propelled her to the top of her profession.

Higgins was born in Hong Kong, the only child of a French mother and American father who met in Paris during World War I, when her father had joined the French army as an ambulance driver during the war.

The family moved to California in 1925, where Higgins attended the prestigious Anna Head School in Berkeley, where young ladies learned the finer points of English and French. Her mother took a job teaching there in exchange for her daughter’s admission. She would graduate with honors from the University of California-Berkeley in 1941 with a Bachelor’s Degree in French, before earning her Masters in journalism from Columbia in 1942.

Higgins cut her reporter’s teeth in California at the weekly Tahoe Tattler, UC-Berkeley’s Daily Californian and the Vallejo Times-Herald. Working part-time for the New York Herald Tribune as Columbia’s campus correspondent, Higgins managed to snag an interview with Madame Chiang Kai-shek, wife of China’s first lady — a feat that led to her becoming only the second female reporter hired by the Tribune.

And though not the Trib’s only female reporter, she was fiercely competitive when it came to chasing down a story with, as her city editor noted, more “fire and zeal than most.” Which, in the newsroom, roughly translated to a reputation for stealing stories and playing “dirty tricks” like checking out all the library’s sources for background on a story so no one else could get them.

Nazi death camps

In 1944, she got her first overseas assignment by bypassing her editor and appealing directly to the paper’s female publisher. Assigned first to the London bureau, then to Paris because of her fluency in French, Higgins was just 24. The next year, she was named the Herald Tribune’s Berlin assistant bureau chief, chasing stories with what her publisher recalled as “a single-mindedness and determination.” Those qualities apparently served her well, since she earned a large share of the front-page, above-the-fold coverage of the capture of Munich and the liberation of the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps.

Her accounts of the camps won her the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award as best foreign correspondent of 1945 because of powerful reporting like this: “This correspondent and Peter Furst, of the Stars and Stripes, were the first Americans to enter the enclosure at Dachau, where persons possessing some of the best brains in Europe were held during what might have been the most fruitful years of their lives.” She also reported on the Nuremberg trials and Berlin blockade.

‘Enterprise and courage’

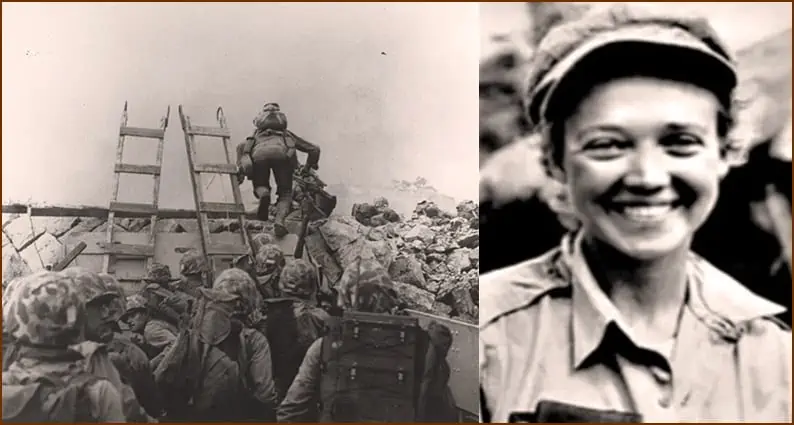

In 1950 she was sent to Tokyo as the Herald Tribune’s Far East bureau chief when, almost immediately, she wound up in Korea as the only female war correspondent covering the Korean War. But the Tribune also sent its star war correspondent, Pulitzer Prize-winner Homer Bigart, to Korea. As her senior correspondent, he threatened to fire Higgins if she didn’t leave the country. Naturally, she refused to go, choosing instead to compete with him for stories. Their battle of the sexes ultimately resulted in excellent coverage for the paper and Pulitzers for both journalists. In Marguerite Higgins’ case, the Pulitzer jury noted her “fine front line reporting showing enterprise and courage,” before adding, “she is entitled to special consideration by reason of being a woman, since she had to work under unusual dangers.” In other words, not bad for a woman, huh?

Higgins prided herself on being able to accept and adapt to the hardships and dangers of war-zone reporting; most of her colleagues came to accept her as just another reporter. But the military officers were another matter, often telling her that, as a woman, she didn’t belong on the front lines. When a Marine lieutenant general ordered her out of Korea, even appointing an escort to take her to a waiting plane, Higgins did more than just stand her ground. She went over the officer’s head, appealing her ouster straight to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United Nations forces defending South Korea. McArthur not only lifted the ban on female correspondents in Korea, he wired Higgins’ editors to say, “Marguerite Higgins is held in highest professional esteem by everyone.”

‘Movie-star prettiness’

As an attractive blue-eyed blonde covering a war full of men, Higgins fell prey to all manner of gossip and innuendo. Tall, at 5′ 8″, she was described by one Tribune staffer as having “a sort of movie-star prettiness, almost like a cross between Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe, with a super figure and those absolutely blue eyes.” But, according to Chicago Daily News correspondent Keyes Beach, who served with Higgins in Korea, “Maggie didn’t need to use her sex to do a good job as a war correspondent. She had brains, ability, courage and stamina.”

In 1952 Marguerite Higgins had married Lt. Gen. William Hall, who had been in charge of the United States Intelligence in Berlin. In 1955 they settled in Washington, DC, where she covered the State Department and wrote an editorial column one day a week. The couple went on to have three children, one of whom died in infancy.

World leader interviews

Higgins continued traveling overseas in the early 1960s, covering foreign affairs and interviewing top world leaders like Francisco Franco, Nikita Kruschev, Jawaharlal Nehru and Iran’s Shah Reza Pahlavi. In Africa, she covered the 1960 Congolese civil war. She used her column to write about the Communist threat and, in 1962, provided an early warning of Soviet military activity in Cuba. She went to Vietnam twice in 1963 to report on the campaign of civil resistance led mainly by Buddhist monks, alleging their headline-grabbing self-immolations were politically inspired to help topple the Diem regime and charging Diem’s overthrow was the result of American pressures and policies. In 1965, she wrote Our Vietnam Nightmare, detailing her firsthand investigations as well as personal criticisms of America’s involvement in Vietnam.

Higgins left the Herald Tribune in the fall of 1963, moving to Newsday on Long Island, where she wrote a column three days a week that was syndicated in 92 other newspapers. It was a pace she managed to keep up until just a week before she died.

Marguerite Higgins’ death came at the age of 45, caused by Leishmaniasis — a tropical infection she picked up from the bite of a sand fly during a long tour of Vietnam, Pakistan and India. Hospitalized in Washington, DC, she died in January of 1966 of complications from the infection. To honor her for her front-line war reporting, Marguerite Higgins was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, just outside Washington, DC, next to her husband.