When Mary Eliza Mahoney graduated in 1879 as America’s first professional nurse, she stood on the shoulders of giants. Jamaica’s Mary Seacole nursed soldiers during the Crimean War; Harriet Tubman and Susie King Taylor tended the Civil War’s wounded; and Namahyoke Sockum Curtis battled typhoid, yellow fever and malaria as a nurse during the Spanish-American War.

Born in 1845 to freed slaves who traveled to Boston from North Carolina, Mary Mahoney was educated at the Phillips School, named for the father of abolitionist Wendell Philips and considered one of the best schools in the city. In 1855, by an act of the Massachusetts legislature, it became one of Boston’s first integrated schools.

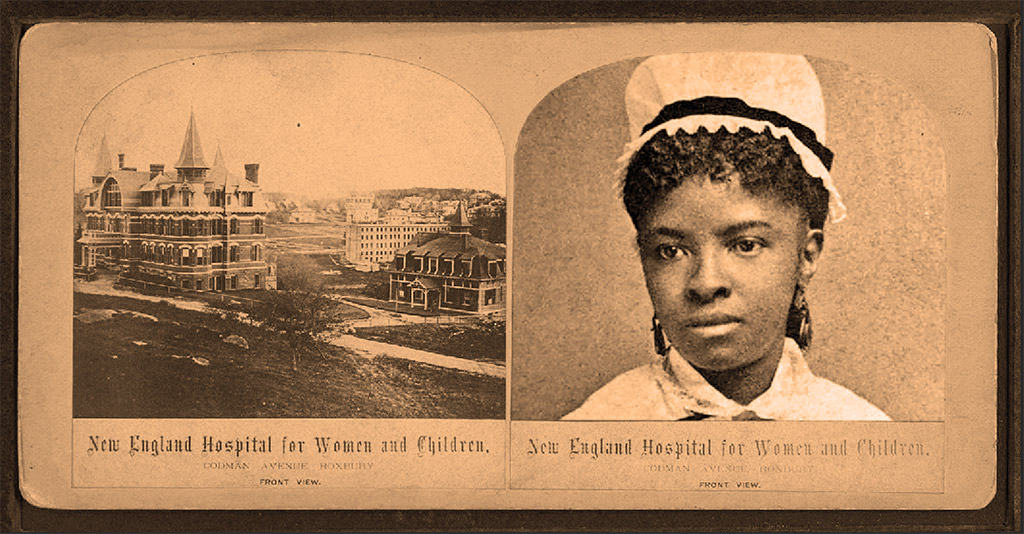

She had always wanted to be a nurse when she started working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, known today as Dimock Community Health Center. NEHWC was the first hospital in New England, and the second in America, established and operated by women for women. Exceptional for its place in the history of women in medicine, it had an all-female physician staff.

Mary Eliza Mahoney was there for 15 years, working in various capacities as a cook, janitor and laundress. More importantly, she had the opportunity to work as a nurse’s aide, gaining valuable hands-on experience.

NEHWC also operated one of America’s first nursing schools at a time when African American nursing students were routinely excluded from white hospital-based nursing schools. Every year, a select few were admitted to meet rigidly enforced institutional quotas in what amounted to de facto segregation. The NEHWC was one of those institutions, limiting its admission of black students to two a year. And in 1878, at age 33, Mary Mahoney became one of them.

The school’s 16-month program was rigorous. Students received 12 months of medical, surgical and maternal health training, attending lectures and afforded valuable hands-on hospital experience. Four months of private-duty nursing in local Roxbury homes followed. Students worked from 6 AM until 9 PM and, in their free time, were expected to do chores like laundry, ironing and cleaning.

Of the 42 students who entered the school in 1878, only four completed the course, graduating in 1879. Mary Eliza Mahoney was one of them, making her the first African American woman in the United States to earn a professional nursing license.

If nursing school was tough, it was nothing compared to the discrimination she encountered in her attempt to pursue a career in public nursing.

But if nursing school was tough, it was nothing compared to the discrimination she encountered in her attempt to pursue a career in public nursing. Graduate black nurses had limited practice opportunities and earned lower wages than their white colleagues. They could care for black clients in their homes as private-duty nurses, or limit their hospital practice to caring for black patients only. And their exclusion from membership in professional nursing organizations denied them legitimacy in an America that already harbored preconceived ideas about the competence of black nurses.

Faced with this reality, Mary Eliza Mahoney chose to work as a private-duty nurse, her clientele consisting mostly of wealthy white families up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Known for her patience, efficiency and her gentle, calming bedside manner, she received requests from patients as far away as New Jersey, Washington, DC, and North Carolina.

She also joined the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the U.S. and Canada, today’s American Nurses Association, in 1896. But when she realized black nurses were not always welcome, she began to advocate for the equality of African American nurses, founding the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) in 1908. At the organization’s first national convention in 1909, Mahoney used her welcome address to call out the inequalities in nursing education.

“Deeply religious, small of stature, about five feet in height and less than 100 pounds … most interesting and possessed of an unusual personality and a great deal of charm.”

In her 1929 book, Pathfinders: A History of the Progress of Colored Graduate Nurses, Adah Thoms described Mahoney’s presence at the convention. She was “deeply religious, small of stature, about five feet in height and less than 100 pounds … most interesting and possessed of an unusual personality and a great deal of charm … an inspiration to the entire group of nurses present.” Thoms would become the first nurse to receive the Mary Mahoney Medal in 1936. Following her speech, Mahoney was made a lifetime member of the NACGN and elected its chaplain. She worked tirelessly to recruit women of color to join the NACGN. In 1910, the number of black nurses in the United States was about 2,400; within 20 years, that number more than doubled.

After a 40-year career spent caring for others, Mary Eliza Mahoney retired. Always a strong advocate for women’s rights, at the age of 76, she was among the first women who registered to vote in Boston when the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. Diagnosed with breast cancer three years later, she battled the disease for several years before she passed in 1926 at the age of 80. Buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts, her grave is now a memorial site.

Small in stature, but mighty in character, Mary Eliza Mahoney changed the face of professional nursing in the United States and has been recognized with numerous awards. In 1936, the nurses’ organization she founded in 1908, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, established the Mary Mahoney Award, given to nurses who promote integration within the profession. To this day, it is presented annually by the American Nurses Association. The American Hospital Association inducted her into its Hall of Fame in 1976. And she joined the ranks of a formidable group of female pioneers in 1993 when she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.