If visitors to New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery in the Spring of 2018 felt the ground shift a little beneath their feet, it was probably just Mabel Rosalie Barrow Edge — once known as America’s most militant conservationist — rolling in her grave.

It was in April of that year the Trump administration gutted the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), one of the country’s first environmental laws, designed to prohibit the unregulated killing of birds and protect migratory bird populations. Among other things, its rollback means neither people nor companies can be held accountable for killing birds, even should a repeat of a horrific event, like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that killed or injured up to a million birds, occur.

New York Socialite

The youngest of five children, Mabel Rosalie Barrow was born into a wealthy, socially-prominent New York City family in 1877. She received a private school education and became a socialite in her own right. At age 32, she married Charles Edge, a British engineer who made his fortune in the ship and railroad industries. After three years of traveling abroad, the couple returned to America, settling in New York.

Women’s Suffrage

It was during one of their trips abroad that Edge got her first taste of social activism after meeting a prominent figure in Britain’s women’s suffrage movement. Listening to Sybil Margaret Thomas rail about England’s male-dominated political machine, Edge was bitten by the feminist bug. Once back home, she put her considerable intellect and assertive nature to use in the Equal Franchise Society in 1915, then became an officer in New York State’s Woman Suffrage Party, where she worked alongside Carrie Chapman Catt. Her experience fighting for women’s rights would stand her in good stead for future battles that lay ahead in the environmental/conservation movement.

Wildlife Activism

She first became interested in birds in the 1920s, at her summer home in Rye, New York. Throughout the rest of the year, she joined well-known ornithologists and other amateur birdwatchers with their binoculars in Central Park, eventually logging 804 different species she had observed.

But hobby turned to passion after Edge learned about the slaughter of 70,000 bald eagles in Alaskan. Starting in 1917, in response to fears from farmers and salmon fishermen, Alaska enacted bounty laws by which hunters were paid $1 to $2 for every eagle they took; the birds’ feet would be cut off and presented as proof to claim the bounty. Closer to home, Edge also denounced the then-popular practice of appreciating and studying birds by killing and mounting them regardless of how rare the species.

Though private schooling had given her no education in the natural sciences, Edge was educated by prominent forest and wildlife professionals, soon amassing enough knowledge to write and advocate on conservation topics ranging from the importance of preserving birds of prey and species diversity, to the dangers of toxins and pesticides, including DDT, and the importance of protecting virgin forests.

In 1929, at the age of 52, Edge read of the actions of a well-known wildlife organization raking in big bucks by “renting” their sanctuaries to hunters and trappers. One of them was the National Association of Audubon Societies (now known as the National Audubon Society). A lifelong member of the NAAS, Edge was outraged, and determined to bring about reform.

Putting her activist background to good use, she formed the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC) and used what, back then, would have been considered guerilla tactics to expose the NAAS. At meetings, she would ask embarrassing questions NAAS leaders couldn’t answer without incriminating themselves; revealed to audiences they had been well compensated for opening their Louisiana sanctuary to muskrat trappers harvesting the animals for their fur; and obtained the NAAS mailing list so she could send incriminating articles directly to other members. Membership dropped; top NAAS big shots were fired; and fur trapping at the sanctuary was halted.

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

But Rosalie Edge was far from done. In 1932, she learned the Pennsylvania Game Commission — not unlike the Alaska Territory years earlier — had, since 1929, been offering a $5 bounty for every goshawk shot, as the birds were considered nothing more than vermin. After an amateur photographer traveled to a place called Hawk Mountain along the Appalachian Trail in Pennsylvania, returning with photos of dead and dying birds, his pictures shocked the conservation community and galvanized Edge.

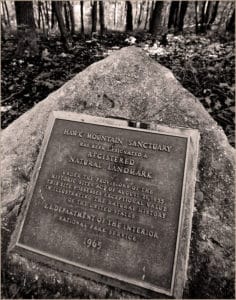

Deciding enough was enough, she bought up the property and transformed it into a sanctuary. An initial loan of $500 for a lease-purchase option on roughly 1,400 acres eventually grew to 2,600 acres — Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, on the Schuylkill-Berks County line in southeastern Pennsylvania is the world’s oldest sanctuary for birds of prey. A National Natural Landmark registered in 1965, it is entirely self-sufficient.

Never one to rest on her laurels, Edge then started successful national campaigns leading to the creation of Olympic National Park in 1938 and Kings Canyon National Park two years later, put her organizing skills to use, lobbying Congress to purchase about 8,000 acres of old-growth sugar pines on the perimeter of Yosemite National Park that were slated to be logged.

Rosalie Edge brought her considerable influence to bear on the founders of The Wilderness Society, National Conservancy, the Environmental Defense Fund and just about every other wildlife protection and environmental organization created during and after the 30 years when she dominated America’s conservation movement. In 1960, her Hawk Mountain Sanctuary provided author Rachel Carson with the avian migration data she needed to link the decline of juvenile raptor populations to the pesticide DDT in her groundbreaking bestseller, Silent Spring.

Mabel Rosalie Barrow Edge died in November of 1962 and was laid to rest in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery. But earlier that month, she attended the National Audubon Society’s annual meeting in Texas. Her work decades earlier to expose the hypocrisy of the NAAS resulted in a long-term, bitter feud between them. But at the Audubon Society’s banquet, she was introduced as one of the most prominent figures in American conservation to enthusiastic applause. The event would be one of her last public appearances. But the legacy and dedication of Mabel Rosalie Barrow Edge lives on in the field of women’s rights and America’s environmental conservation movements.