We hear a lot about privilege these days. And this Wednesday’s Woman, Lillian Wald, would be the first to tell you she was born into privilege — the daughter of wealthy German-Polish parents whose families fled Europe seeking economic opportunity. She once described herself as a well-educated, frivolous, spoiled socialite. But two pivotal events shaped this frivolous, spoiled socialite into a humanitarian and visionary who dedicated her life to helping others.

Wald received her early education at Miss Cruttenden’s English-French Boarding and Day School in Rochester, NY. She lived life as a society girl until, one day, she was sent to get a nurse for her sister, who was laboring to deliver her first baby. With professionally trained nurses hard to come by in the 1880s, the skill and compassion this young nurse showed as she tended her sister impressed Wald and sparked her curiosity about nursing as a career. As a result, Lillian Wald enrolled in the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, graduating in 1891.

The Lower East Side

After spending a year as a nurse in an orphanage, Wald entered Women’s Medical College at age 22 to become a doctor. Her studies took her to New York’s Lower East Side, where she saw how poor immigrant families struggled to cope with their meager circumstances. One of her assignments was to design a home nursing plan, teaching health and hygiene in the community.

It was during this period Wald experienced what she called her “baptism by fire.” After teaching a class, one of her young students led her down a narrow street and up the stairs to a rear tenement where a family of seven shared two rooms with paying boarders. There she found her student’s mother, lying on a dirty bed soaked with two days of post-partum hemorrhage.

Nurse in residence

That visit left her shaken and “ashamed to be part of a society that permitted such conditions to exist.” The experience made her realize where her true responsibilities lay and what her life’s work should be. When Lillian Wald realized she could be of greater use if she focused on bringing affordable health care to those on the Lower East Side, she left medical school and decided to live within the immigrant community on the Lower East Side.

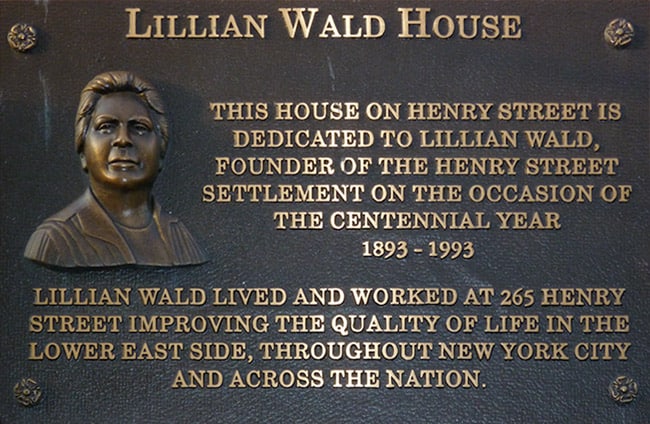

Wald first moved into the neighborhood and opened an office to treat the community’s medical needs, becoming America’s first public health nurse. But as the community grew to trust her, she hired four nurses and eventually moved her office to Henry Street in 1895 — her Henry Street Settlement is still in operation.

Affordable health care advocate

With affordable health care her first priority, Wald pioneered public health nursing, even coining the name of the profession based on the idea that nurses needed an “organic relationship” with their neighbors. She operated on a sliding-scale fee, with her team of nurses responding to calls from doctors, charities and individuals in need.

Eventually working with 92 nurses and a full office staff, Wald’s public health nurses did more than respond to medical needs. They taught basic sanitation and hygiene, cooking, and even sewing. She extending the services of public health nurses by starting the first American public school nursing program in New York City. When she convinced Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to provide coverage for home nursing services, other insurance companies followed MetLife’s lead. And as a result of her series of nursing lectures, the Teachers College of Columbia University established the first university program for the training of public health nurses in 1910.

Vulnerable children

Because so much of Lillian Wald’s work centered on children — and knowing Lower East Side children had no place to play save for their narrow streets crowded with traffic of all kinds — she converted three back yards into a small playground during her first summer on Henry Street. She pressured the city to provide educational opportunities for children with physical and learning disabilities, and establish school lunch programs. She successfully lobbied for the position of New York City’s first school nurse. And her vision of a federal organization dedicated to children’s welfare and ending child labor became a reality when the Children’s Bureau was established in 1912. She also used her considerable contacts to secure funding that kept needy children in school rather than turn them out into the workplace.

First women’s peace march

Lillian Wald was also a suffragist who fought for women’s right to vote and supported her employee, Margaret Sanger, in the battle to give women the right to birth control. In 1910, when a six-month overseas trip opened her eyes to international humanitarian issues, Wald’s belief in women’s suffrage and peace led her to protest America’s entry into World War I. But once war became inevitable, she did her part, chairing the Committee on Community Nursing of the American Red Cross. She joined the Women’s Peace Party and helped organize the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, helping lead the first women’s peace march in 1914.

Lillian Wald also campaigned for civil rights and the end of segregation in an era of systemic racism. She cofounded Lincoln House to provide care to black New Yorkers and hired the first black public health nurse to work with tuberculosis patients. And in 1915 she joined Henry Street colleagues Florence Kelley and Henry Moskowitz in hosting what would become the first meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — the NAACP.

Presidential commendation

Lillian Wald received numerous awards and accolades throughout her life. Chosen as honorary chair or advisor to almost 30 state and national public health and social welfare organizations, she was awarded the gold medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences in 1912. In 1922, she was named one of the 12 greatest living women by the New York Times and, later, Outstanding Citizen of New York. And on the occasion of her seventieth birthday, in 1937, the public gathered to honor her; commendations were read by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and New York Governor Lehman, and New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia granted her the city’s distinguished service certificate.

A health-care pioneer, Lillian Wald saw health not as an individual matter, but as a reflection of the larger community. She saw the link between poverty and poor health, and knew that the solution to the underlying problem had to be a matter of public interest. And although she had a platform of broad social, economic and political issues, she kept her focus on personal connections; as she conducted studies and gathered statistics, she knew her results weren’t just numbers, but her friends and neighbors.

Lillian Wald died at her home in Westport, CT, in 1940, at age 73, after a long illness precipitated by a cerebral hemorrhage. Thousands of people whose lives she had touched through her work mourned her. She once said nursing was love in action, and she lived by that simple truth until the end of her life. She is buried alongside her sister beneath a simple stone at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, NY.

Wonderful article , as a nurse I have read about her but want to know more .

I am planning a trip with some other retired nurse’s to go to the Henry Street Settlement in the Fall.

What a remarkable woman!!

This is the first time I saw your website and will definitely re- visit .

Thanks

Inspiring story much needed in dire times. Thanks Sandy.