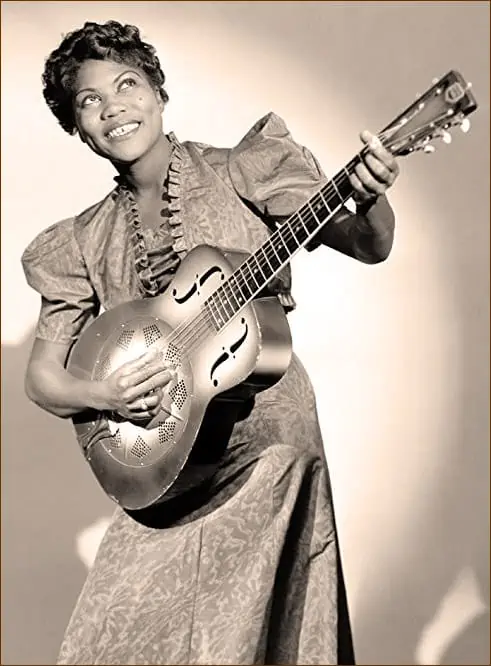

When Sister Rosetta Tharpe picked up her electric guitar in the 1940s and lit into “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” she didn’t know she was creating a musical style that would become an international sensation. But today, this audience-taunting, duck-walking, howling, stomping, gospel-singing black woman is known as the Mother of Rock and Roll.

Rosetta Nubin was born in 1915 in Cotton Plant, AR, to a family of religious singers, cotton pickers and tent evangelists. At 19 she married a preacher named Thomas Tharpe; she divorced him, but kept his surname as her stage name. She picked up her first guitar at age four; two years later, she was performing on the traveling evangelist circuit throughout the South with her mother. Throughout her career, she crossed lines, broke norms and inspired young men who would adopt her style and make it their own. In fact, if not for Sister Rosetta Tharpe, there would be no Little Richard, no Jerry Lee Lewis, no Chuck Berry nor Elvis Presley.

Shocking lyrics

Female guitarists were rare in the 1930s. And Tharpe was a young, innovative black female experimenting with both religious (“Precious Lord, Take My Hand”) and secular (“I Want a Tall Skinny Papa”) music as well as pioneering the use of a newly-invented instrument — the electric guitar. Her suggestive lyrics shocked her gospel fans, but her guitar style, vocal range and blues-gospel mix made her a trailblazer. By 1938 she was performing with Cab Calloway with the Cotton Club Revue. That same year, at age 23, she recorded her first single for Decca Records, “Rock Me,” recognized today as pop-gospel.

She collaborated with jazz greats like Duke Ellington and legendary gospel group The Dixie Hummingbirds, even teaming up with the all-white Jordanaires to perform for mixed audiences. But it was still 1940s America; racism was rampant, with hotels and restaurants closed to African Americans. But racism never broke her spirit or dulled her exuberance. Tharpe got used to sleeping on buses and going around to the back of restaurants for a meal when she wasn’t allowed in.

Wartime fame

During World War II, Sister Rosetta Tharpe was so popular with black soldiers she was one of only two black gospel acts to record V-discs (“V” for Victory) for GIs overseas and appear on Jubilee, a variety show for African American servicemen and women.

As the war ended, atomic bombs fell, and a black man named Jackie Robinson was signed to baseball’s major league, Tharpe produced her most famous spiritual, “Strange Things Happening Everyday,” giving voice to how the world was changing. Considered the first gospel song to cross over to Billboard’s “race” (later to become known as R&B) charts, it reached #2 and became one of the earliest models for rock and roll.

The making of Little Richard

It was in 1947 that Tharpe invited a 14-year-old boy named Richard Wayne Penniman onto the stage to perform with her in Macon, GA. When she paid him after the show, Little Richard recalled it was then and there he decided to drop his last name and become a professional performer.

But her biggest gig was when she married for the third time. Tharpe had long pursued relationships with both sexes, a secret she kept from her fans. But in 1951 she married Russell Morrison, her manager, in Washington, DC’s, Griffith Stadium in front of more than 20,000 paying customers. A combination wedding-concert, fans cheered as Tharpe shredded electric guitar from center field. The event was recorded and later released as an album. It was also the first-ever stadium concert, predating the Beatles’ Shea Stadium concert by 14 years.

White expropriators

But as young white men dominated the rock and roll scene in the 1960s, adopting and experimenting in their names with music she had invented, Tharpe saw her career decline. Ironically, her New York Times obituary noted she was criticized for putting “too much motion as well as emotion into her singing” — a performing style embraced by Elvis “The Pelvis” Presley, Chuck Berry as he duck-walked across the stage, and Jerry Lee Lewis’ antics in “Whole Lotta Shakin”.

But Sister Rosetta Tharpe was nothing if not resilient. While American tweens and teens screamed for Elvis, Chuck and Jerry Lee, she took her considerable talents to Europe. One of her most famous performances, available on YouTube, was in 1964, at an abandoned train platform in South Manchester, England. On a cold, rainy day, she played, sang and shouted “Didn’t It Rain?” for a young crowd. She continued to tour Europe almost until the end of her life, making her last recording in 1970 in Copenhagen.

Her years in Philadelphia

Tharpe and her husband had moved to Philadelphia in the early 1960s. And it was there she made some of her finest records, releasing five LPs and earning a Grammy nomination for her 1968 album, “Precious Memories.” But life took a turn in 1968 when her mother passed and she was diagnosed with diabetes, throwing her into a spiral of depression. Two years later, Tharpe had her first stroke, which would result in the amputation of a leg from diabetic complications.

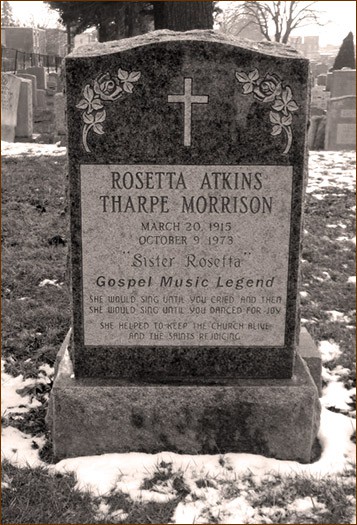

She suffered a second stroke while preparing for her next recording session, and died in Temple University Hospital in 1973 at the age of 57. Tharpe was buried in Northwood Cemetery in an unmarked grave. But in 2008, a concert was held to raise money for a grave marker, placed later that year. Today a rose-colored monument bears witness to one of America’s most influential artists of the 20th century.

That same year, the PA Historical and Museum Commission approved a Historical Marker at Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s home at 1102 Master Street in Philadelphia’s Yorktown neighborhood. Listed for sale in 2018 with an estimated worth under $225,000, the listing cites the size of the home, nearby schools, stores, pizza places and a playground … but there is no mention that the Mother of Rock and Roll once lived there.

Chuck Berry

A member of the International Gospel Music Hall of Fame, Sister Rosetta Tharpe was finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017. Michael Harriot, writing for The Root, once said, ” … her distinct sound was as if one of God’s angels drank a fifth of gin and figured out a way to plug an extension cord into its harp.” Chuck Berry insisted his entire career was “just one long Rosetta Tharpe impersonation.”

But Sister Rosetta Tharpe, hearing people say she “played like a man,” had the final word: “Can’t no man play like me. I play better than a man.”

Agreed!

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was truly ahead of her time.