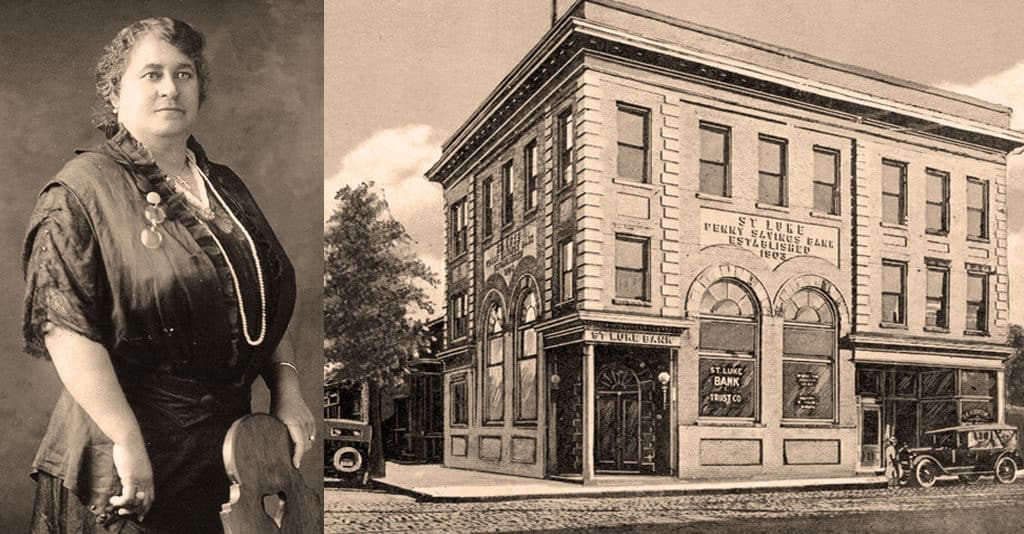

In 1903 in Richmond, Virginia, Maggie Lena Walker knocked the banking industry on its ear. She founded and became president of a bank, making her the first female bank president in the history of the United States. In an age when the financial services industry was captained by wealthy white men, her achievement was even more noteworthy given that Walker was the daughter of two former slaves.

Born in 1864 as the Civil War raged across Virginia, Walker’s mother — Elizabeth Draper– was a freedwoman working as a cook, who married a freedman — William Mitchell — working as a butler in one of Richmond’s downtown hotels. Her mother worked as a laundress to help support Maggie and her younger brother.

Young Maggie later described that experience: “I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but with a laundry basket practically on my head.” But working with her mother forged a strong work ethic and exposed her to basic business practices.

The laundry did well enough to send Maggie to a Quaker-run school and, in 1883, graduate from the Richmond Colored Normal School at the top of her class. She took a teaching position during the day, pursued evening classes for herself in accounting and business, and ultimately met and married a prominent Richmond building contractor. Their marriage lasted 29 years, until her husband was shot and killed in a bizarre accident by his eldest soon, who mistook him for a burglar.

Maggie Walker suddenly found herself in charge of managing not only a household, but a large estate from her late husband’s business, along with $8,500 in life insurance benefits (today worth about $211,000). That, plus her own savings and a history of good investments over the years, provided security for her family.

In the wake of her husband’s death, Walker devoted much of her time and attention to a mutual-aid society founded in Baltimore in 1867 by former slave Mary Prout — the Independent Order of St. Luke. Walker had joined the local council at age 14, just as Reconstruction was ending and Jim Crow began to take hold. At the time, it provided life insurance, burial benefits and care for the sick, the elderly and the destitute.

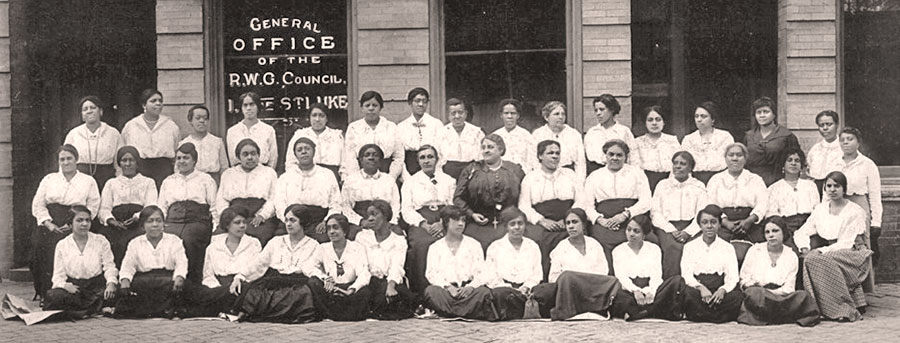

But Walker envisioned St. Luke’s doing much more. Now, with a respected normal school education bolstered by knowledge of business and accounting, she set her sights on strengthening and expanding the institution — especially in the areas of education and employment for women.

Turning nickels into dollars

She established a small community insurance company for women and, in 1903, founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and, making both fiscal and gender history. The bank was a powerful tool for black self-help in the Jim Crow South. It not only served Richmond’s adults; it taught the importance of saving to black children by giving out small banks that encouraged them to save. Or as Walker said in address to the St. Luke Annual Convention in 1901, “let us have a bank that will take nickels and turn them into dollars.”

By 1924, the bank had grown to more than 50,000 members. And while the Great Depression saw the collapse of many of America’s banks, St. Luke’s survived. It eventually merged with two larger banks to form Consolidated Bank and Trust Company — the oldest continuously existing black-owned and black-run bank in the country. It continues to operate today in Richmond as the Premier Bank: Consolidated Division.

Black economic power

Walker always believed in the black community’s ability to harness its own economic power. In the early 1900s, she published the weekly St. Luke Herald, encouraging Richmond’s African-American residents to establish their own institutions. And she opened the Emporium — a department store (which, conveniently, housed a bank) in downtown Richmond. Her aim was to draw residents from the city’s white-owned stores and their discriminatory policies against blacks that made them enter through separate doors and barred them from sales floors, dressing rooms and showrooms.

Civil rights advocate

Walker had been a civil rights activist since her days at the Richmond Colored Normal School. In 1883, she joined one of the first recorded school strikes in America when she and the other nine African Americans in her class protested Richmond’s discriminatory policy of separate graduation ceremonies for white and black students. Rather than graduate in a church, as the school district planned, Walker and her classmates won the right to graduate from their own school.

She later became one of four black bank presidents who organized and led a nine-month boycott of Richmond’s newly-segregated streetcars in 1904. Walker also spearheaded 1920 voter registration drives after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote; by October of that year, 2,410 black women had registered to vote in the November presidential election.

A staunch believer that education was the best way to level the socioeconomic playing field for African Americans, Walker worked with America’s most prominent black educators, civil and women’s rights activists and social reformers of the day — Mary McLeod Bethune, Janie Porter Barrett, Nannie Burroughs and Charlotte Hawkins Brown — to ensure quality education for black children, and contributed generously to the schools founded by each woman.

Role model for the disabled

Already diagnosed with diabetes, Walker suffered a fall in 1907 that damaged the nerves in her knees to the point where she developed paralysis and, by 1928, was confined to a wheelchair.

But hers was no run-of-the-mill wheelchair. She customized a comfortably upholstered armchair mounted on a wooden base with wheels. It was fitted with sturdy metal grab bars on each side, along with a generous foot rest and a polished wooden desk that was attached so she could continue to work.

She also equipped her home with an elevator and had her Packard car modified to accommodate the wheelchair. Though limited in movement, she remained a strong force and a leader in Richmond’s African-American community.

Legacy

Maggie Lena Walker retired in 1933. Known during her last years as the “Lame Lioness,” she succumbed to diabetic gangrene and died at home in 1934 at age 70.

Active for more than 50 years in Richmond’s business and educational life, her funeral drew thousands. She was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, created in 1891 as a burial ground for Richmond’s African Americans, who could not be buried in white cemeteries.

Today her house is a National Historic Site. Built in 1883, the house and its contents were purchased by the National Park Service in 1979. Now open as a museum, the 28-room urban Victorian mansion is restored to its 1930s appearance.

Richmond built the Maggie L. Walker High School, one of two local high schools for black students, during America’s era of segregation. After seeing generations of students graduate, it was totally renovated, reopening in 2001 as the Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School for Government and International Studies. And in the summer of 2015, a larger-than-life statue of Walker was unveiled on Richmond’s Broad Street, depicting a 10-foot-tall Maggie Lena Walker with glasses pinned to her lapel and a checkbook in her hand.

Known throughout her life as a grand woman who loved feathers and hats and snazzy cars, Maggie Lena Walker was tough, demanding and persistent in her vision to improve life for African Americans and women. Today she is recognized as one of the most profoundly influential activists of her time.