Talk about a tough old broad. Annie Edson Taylor was the first, and the oldest, person to survive a tumble over Niagara falls in a pillow-padded barrel of her own design. At a time when women were expected to be docile, delicate and fragile, Annie Edson Taylor was a fearless, foolhardy badass.

The plucky 63-year-old widow and one-time charm school instructor crawled into a white oak barrel measuring just under five feet high by three feet wide on an October afternoon in 1901 before tumbling into the chaotic froth and churn of rocks and raging water in a quest for fame and fortune.

Lifelong thirst for adventure

Born one of 11 children in 1838, she enjoyed a comfortable childhood in New York’s Finger Lakes region. Descendants described her as having a dreamy disposition, a lively imagination and a lifelong thirst for adventure. But it was a run of bad luck that, in 1901, brought her to the precipice of Niagara Falls.

While working as a teacher, she met the man who would become her husband. Married at 17, she gave birth to a baby who died within days. More bad luck followed when her husband reported for duty in the Civil War and never returned, leaving Taylor widowed at the age of 25 with almost no money to her name.

In dire financial straits, she took one job after another in an effort to secure her future. Her travels took her from Michigan to Texas and Mexico City and back to Michigan — two desperate years spent thinking about how to make money honestly and quickly. It was during this time, as she mulled one get-rich-quick scheme after another, she came smack up against the adventure she had always sought.

Newspapers reported the story of how she was on a stage coach that was robbed by the Jessie James gang. Taylor emerged from that encounter with $800 sewn into the hem of her dress that went undetected. She also reportedly survived a house fire in Tennessee and an earthquake in South Carolina.

Back in Michigan, and just about broke, she taught the waltz, table manners and rules of etiquette to Saginaw’s children. But as those children grew up and went away, so did the income from Taylor’s charm school.

She would later tell a local newspaper, “I had lost $8,000 some years ago in Chattanooga and my classes in dancing and physical culture did not bring in money fast enough to suit me, so I looked around for something that nobody had ever done before as a means to make some money. The idea of going over Niagara came to me in an instant and I studied the conditions fully before I embarked upon the trip, making the venture with every confidence that I would come out unharmed.”

Which is how a destitute, widowed, stout, graying, 63-year-old female school teacher came to take the ultimate plunge. But only after she had shaved some 20 years off her age when talking to reporters, claiming to be in her early 40s.

While others had challenged the falls in boats, on tightropes and, in one instance, by trying to swim the Niagara just downriver from its treacherous falls, no one had dared go over in a barrel. Taylor read about the huge number of visitors expected at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, and saw an opportunity.

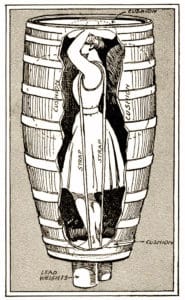

Her work on the perfect barrel went from sketches and prototypes made out of cardboard and string to a local company that made beer kegs — but Taylor insisted on choosing each piece of wood herself. The result was an uneven, oblong barrel less than three feet at its widest, and tapered at both ends. Fitted with a leather harness and cushions to protect her body, it was secured with 10 metal hoops and weighted with an anvil as ballast to keep it upright in the rapids.

The date was set for October 24, 1901, which was Annie Edson Taylor’s 63rd birthday. At just after 4 PM, the Niagara River looked calmer than usual when she climbed into the barrel wearing an “abbreviated skirt” after instructing the men helping her to stand a good ways back for the sake of decency — perhaps a throwback to her days teaching the rules of etiquette. The men then packed the barrel with pillows to surround her. Air was pumped into the barrel using a rubber hose and a bicycle pump; Taylor figured she needed about an hour’s worth of air, though she fervently hoped her feat would take far less time. The barrel was then sealed and towed toward Horseshoe Falls. Once released, observers along the shores watched it bob up and down toward the precipice before it disappeared from view.

In her memoir, Taylor recalled the barrel swooping down the rapids toward the edge, the roar of the falls growing ever louder. After a moment she described as total calm, she felt gravity take over. Seconds later, she hit the surface below, sinking beneath the water. Water began seeping in as the barrel bounced and caromed off the rocks. Almost 10 seconds later, it shot up to the surface of the churning foam, coming into full view to cries and shouts from the crowds. When, about 17 minutes later it became lodged on a reef off the Canadian shore, a riverman hooked it with a boat pole and pulled it in before another gentleman helped saw the barrel’s top off, exclaiming, “My God, she’s alive!”

Taylor, seasick and clutching a sodden pillow, was pulled to safety with nothing more than a small cut on her head and bruises on her body.

‘Goddess of Water’

Her derring-do and miraculous survival were celebrated with shouts of success; the steamer Maid of the Mist blew her horn, and the Boston Globe wrote a few days later that she had accomplished a feat “never attempted except in the deliberate commission of suicide.”

Annie Edson Taylor was even nicknamed the “Goddess of Water.” A poem was written in her honor, with these lines published by her descendants in a 1990 biography:

This great heroine of our nation

has won both fortune and fame.

Now people all over creation

will praise this illustrious dame.

Once safe, she complained only of soreness in her neck and shoulders. But her doctor prescribed strict bed rest and kept visitors to a minimum, fearing she was suffering from “Brain Fever” — a Victorian malady marked by headache, flushed skin, delirium and sensitivity to light and sound caused by emotional shock or excessive intellectual activity. While recuperating in bed, she received a letter with a proposal of marriage which she promptly turned down.

Fame, Fortune, Fraudsters

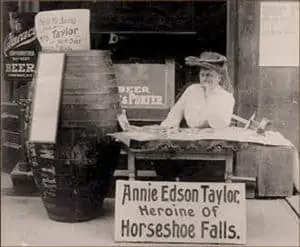

Once Taylor was fully recovered, she penned a slim 1902 book titled “Over the Falls,” describing her remarkable stunt, which she later sold for 10¢ a copy at a “fancy goods and souvenir stand” near the falls, along with miniature barrels and photos of herself.

In the 1910s she returned to the falls to sell her memoir and try her luck at a handful of moneymaking ideas that included working as a clairvoyant and offering “electric and magnetic” medical treatments. She embarked on a few unsuccessful tours and posed for pictures at local fairs. But the one thing she vowed never to do again was take another tumble, claiming, “I would rather face a cannon than go over the falls again.”

The fame she had so desperately sought proved fleeting. Sales of her memoir dwindled, along with her finances, and she fell into poverty. Even worse, she was cheated by fraudsters when her manager absconded with the barrel she intended to use as a prop for speaking engagements. What little money she had left was spent on unsuccessful attempts by private investigators to get it back. The dastardly manager is said to have traveled all over the country with the barrel and a younger, more attractive woman he passed off as Annie Edson Taylor, the Heroine of the Falls. Which was, perhaps, the ultimate indignity.

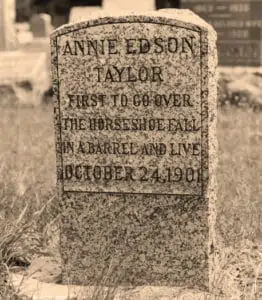

On March 20, 1921, local papers reported Taylor was “an inmate” at the Niagara County Infirmary at Lockport, New York. Having long attributed her ill health and near-blindness to the horrors of plunging over the falls 20 years earlier, she died in relative obscurity at the age of 82 in April of 1921. And although she died in the same financial straits she found herself in before stepping into that barrel, Annie Edson Taylor will always be remembered as the first person to take the tumble over Niagara Falls and live to tell her story.

Her funeral service was held on May 5, 1921; she was buried in a plot donated by the Oakwood Cemetery, near the falls. A group of friends and acquaintances contributed funds to erect a headstone next to the site of her ultimate adventure and greatest achievement.

Sadly, Annie Edson Taylor never found the fame she sought in life. So it’s more than a little ironic that, in death, her legacy lives on with a whole new audience. It turns out Oakwood Cemetery is now offering both narrated-guided and self-guided “Daredevil Tours” in which Taylor is prominently featured at Stop #4.

Afterword

After her stunt, both New York and Canada enacted laws designed to keep others from following in the footsteps of Annie Edson Taylor. Needless to say, they didn’t stop folks from trying. Between 1901 and 1995, 15 people went over the falls; only 10 survived. Among them: Sam Patch, a.k.a. the “Yankee Leapster,” who, in 1829, jumped into the falls from a high tower; and Bobby Leach, a Cockney circus stuntman who survived the plunge in a custom-designed metal barrel in 1911, only to die 15 years later when he slipped on an orange peel during a publicity tour, broke his leg and developed gangrene — he survived the amputation, but died soon thereafter.

She is proud of her success off going over the falls and i did not even know who she was until i read this now i really love her

R.I.P M.s Annie