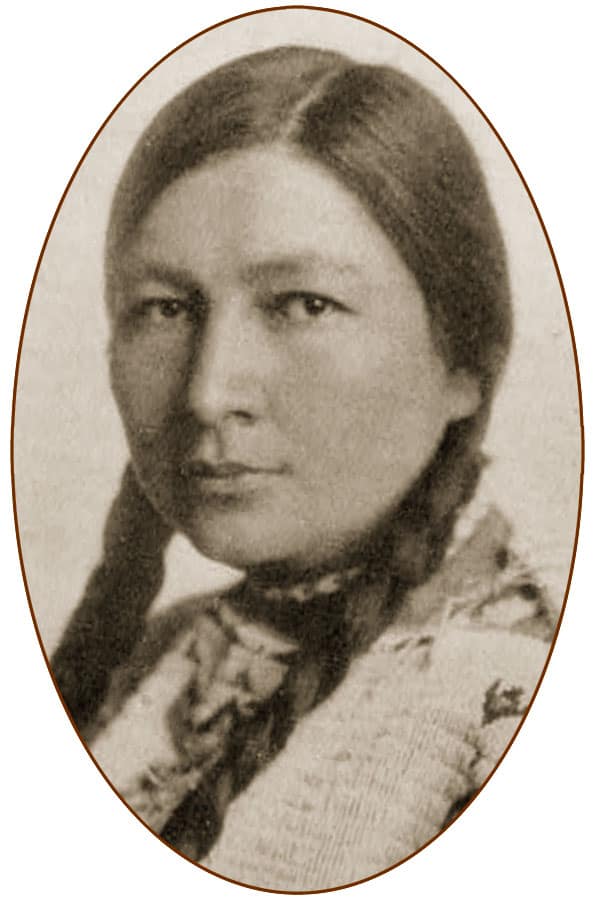

Zitkála-Sá (pronounced Zitkála Shá), also known as Gertrude Evaline Simmons, was born in 1876, year of the Battle of Little Bighorn, on South Dakota’s Yankton Sioux Reservation. Her mother was a full-blooded Dakota Sioux named Ellen Tatiyahewin (“She Reaches for the Wind”) Simmons, her father a white man about whom little is known. We do know he abandoned the family, leaving her mother to raise their children in traditional Sioux ways.

When Gertrude Simmons was eight years old, Quaker missionaries came to the reservation to recruit children for White’s Manual Labor Institute, a boarding school in Indiana. Her mother was hesitant to send her away. But fearing the Dakota way of life was ending, and with no schools on the reservation, she saw this as the only way her daughter could get an education. It was at White’s Simmons learned to write and took an interest in the violin.

Neither wild nor tame

After several years, she was given leave to visit her mother, who encouraged her to stay on the reservation. Caught between two cultures, “neither a wild Indian nor a tame one,” as she later wrote, she remained in South Dakota for four years before returning to Indiana to get her diploma.

Returning to White’s at 15, she continued her study of the piano and violin, leading the school to hire her as its music teacher when a previous teacher resigned. She graduated from White’s Manual Labor Institute in 1895. It was during this period, feeling culturally unmoored, that she took the Lakota Sioux name Zitkála-Sá, meaning “Red Bird,” for herself.

From there, she enrolled in Indiana’s Earlham College on a scholarship, one of few Native American students to join their teacher training program. But months before she could graduate, she was forced to to leave due to illness and financial difficulties, never completing her degree. When she left Indiana for the last time in 1899, she chose not to return home, moving instead to Boston, where she studied violin at the New England Conservatory of Music for a brief time.

Musical prodigy

She then moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and a job teaching music and speech at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School for about 18 months. The school took full advantage of her musical training, featuring her as a soloist with the Carlisle Indian Band. She was, in fact, their most heralded musician. Hailed as “charmingly artistic and graceful,” she toured Europe with the band in 1900, playing as a soloist at the Paris Exposition. While Outlook Magazine described her as “a young girl gifted with musical genius,” another review reflected the paternalism and racism of the period: “The fact of an Indian girl being able to play so marvelously well…is regarded as showing clearly the possibilities of not only lifting the Indian race completely out of the slough of despond, but elevating them to the same plane as that which the advanced man occupies.”

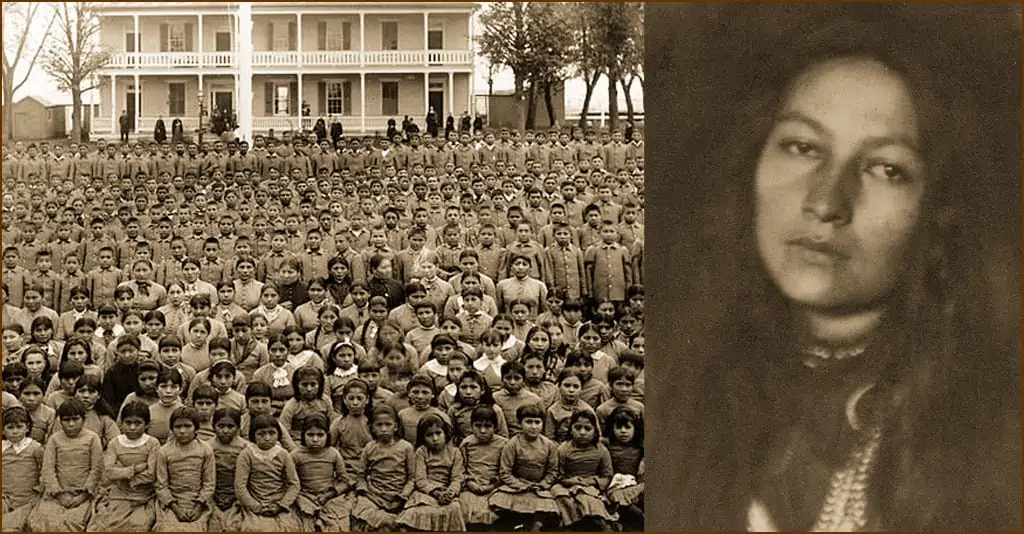

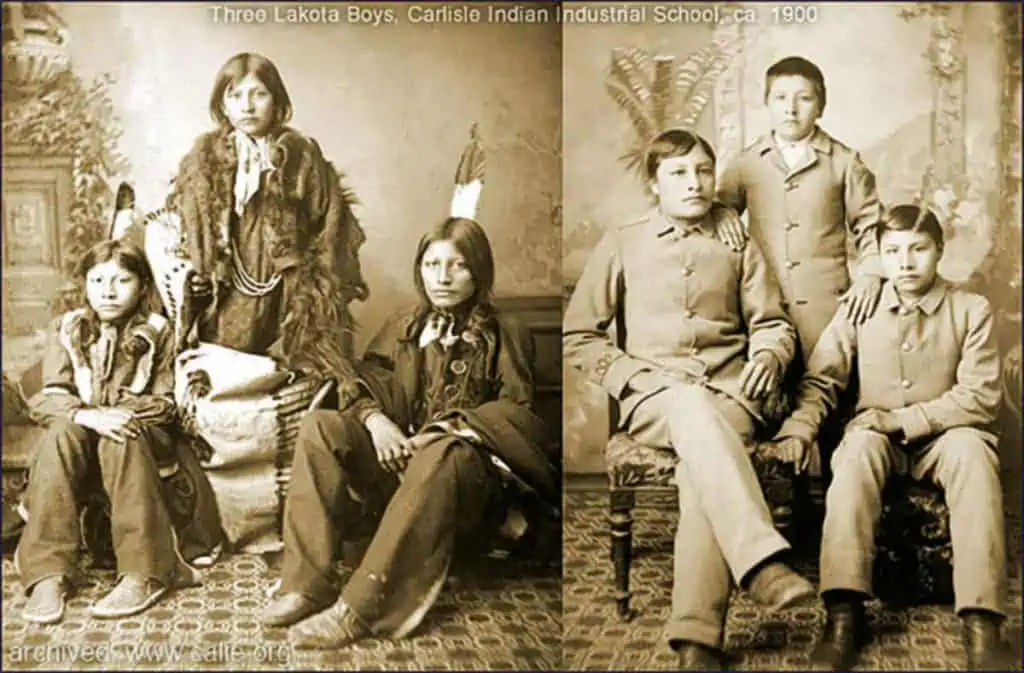

Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded by an army officer who saw education of Native American children as the way to move “from savagery to civilization” in the cruel and misguided belief that “we must kill the savage to save the man.” He exploited students for their labor while receiving government funding for every child recruited from the reservations. Between 1879 and 1918, Carlisle enrolled some 10,000 students from over 141 distinct Native American nations, stripping them of their names, languages, religions and dress in a forced-assimilation program.

Red Bird’s cultural epiphany

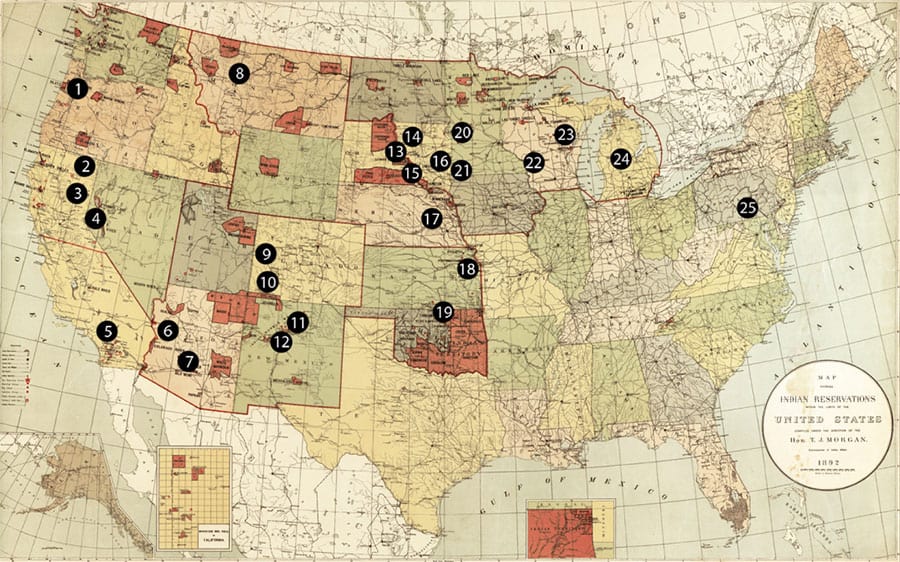

Touting her success at the Paris Exposition, the school sent Zitkála-Sá back to the Yankton Reservation to recruit more students. When she arrived, she was shocked to find her family home in disrepair, her people living in desperate poverty, and white settlers occupying land that had been given to the Yankton Sioux by the federal government.

Returning to Carlisle, she began writing and publishing stories and essays in The Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Magazine under her Lakota name, criticizing the school and facing an onslaught of harsh criticism for not being grateful enough for the kindness and support white people had given her in her education. In the school’s eyes, she had bitten the hand that fed her. Not long after, she either left or was fired from Carlisle, returning to the reservation to care for her ailing mother.

The same year, her book, Old Indian Legends, was published. An anthology of retold Dakota stories, it was intended to build a bridge between the two warring cultures within her. Her work was popularly acclaimed, including by Helen Keller, who wrote to thank her, saying “I have read them with exquisite pleasure.”

Reservation marriage

Back home in South Dakota, Zitkála-Sá had taken a job as a clerk with the Bureau of Indian Affairs office at the Standing Rock Reservation. It supported her financially while letting her pursue her writing about Dakota culture and values. And it was there she met Raymond Bonnin, a mixed-blood Nakota Sioux who lived on the reservation. They married in 1902 and had one son.

Not long after, they moved to Utah, where Zitkála-Sá worked as a teacher on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation; they stayed for 14 years. Her husband served in the U.S. Army during World War I and, years later, clerked at a Washington, DC, law firm.

In 1910, she met William Hanson, a music professor at Brigham Young University. Born and raised in Utah, he had a lifelong interest in the history and traditions of Native Americans. She collaborated with Hanson, writing the libretto for the opera The Sun Dance — the first and only opera to date written by a Native American, much less a Native American woman. The opera premiered to critical acclaim on the Uintah Reservation in 1913, the performance featuring local talent including a group of Ute braves from the nearby reservation. Typical of headlines in newspapers across the country was this, from the Chattanooga Daily Times, dated 7/1/1913: “Squaw Writes Opera.”

Opera as political advocacy

The Sun Dance opera was staged periodically by rural troupes before being performed in 1938 by the New York Light Opera Guild. The Sun Dance ritual that inspired the project was a ceremony of spiritual healing and the most sacred religious event of the Plains Native American communities. U.S. law at that time prohibited tribal nations’ celebration of the Sun Dance. Zitkála-Sá resisted that denial of religious freedom, elevating the sacred tribal chants and dances to what she knew was respected in western society, which was grand opera. By providing a space to perform those sacred dances and songs in public, she was preserving them.

In 1916, Zitkála-Sá became secretary of the Society of the American Indian, the first reform organization administered entirely by Native Americans, and she and her family moved to Washington, DC, where she edited the Society’s American Indian Magazine. Her primary cause was fighting for citizenship for Native Americans; in June of 1924, Congress enacted the Indian Citizenship Act, granting citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States.

Indians denied the vote

But the Indian Citizenship Act stopped short of affording voting rights. In response, Zitkála-Sá co-founded and presided over the National Council of American Indians to unify First Nations in the movement to gain voting rights, healthcare, legal standing and land rights.

She also also worked closely with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC), encouraging them to establish an Indian Welfare Committee and serving as researcher for the committee, investigating land management and probate claims.

Investigative reporting

Writing under her married name, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, she co-authored a scathing report titled Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Grant and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery in 1924, exposing the mistreatment of Native Americans in Oklahoma. Exposing efforts by governments and corporations to cheat Indian tribes out of leasing fees members earned from the development of oil-rich lands, it influenced passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, returning some lands to the tribes as communal property and supporting self-governance and self-management of the lands. And more than 80 years later, it provided inspiration for David Grann, author of a 2017 book titled Killers of the Flower Moon. The 2017 work detailed the 1920’s murders of Osage tribal members who had become wealthy from the deposits of oil on their land.

Sudden death

Three months before The Sun Dance was performed by the New York Light Opera Guild, Zitkála-Sá died unexpectedly at Georgetown Hospital in Washington, DC, at the age of 61, having just returned from a trip to the Yankton reservation.

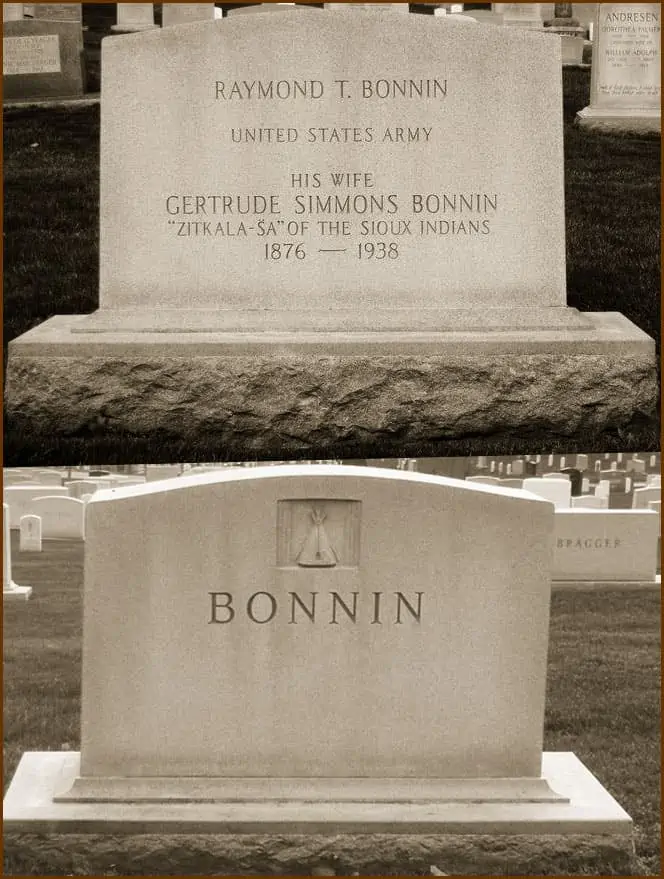

She was buried under the name Gertrude Simmons Bonnin at Arlington National Cemetery, her gravestone marked “Zitkala-Sa of the Sioux Nation,” the image of a teepee inscribed on the back of the stone. The burial honor was given not for her many contributions to the United States on behalf of her people, but because of her husband’s position as a U.S. Army Captain in World War I.

One of the most influential Native American activists of the 20th century, Zitkála-Sá struggled, persisted and triumphed over racism and sexism toward American Indian culture and women. Devoting her life to the protection, preservation and celebration of her Indigenous culture through the arts and political activism, she believed the answer to Native American issues lay with the Indian people themselves.

More than 80 years after her death, Native Americans continue her fight — against the theft of Indian land, in the name of thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous women, and for voter’s rights. That is her legacy, and that is why the voice of Zitkála-Sá resonates to this day.

Thank you ! I discover your website looking for the story of Ztkala-Sa; She was a remarquable et powerful women; I love her.