Elizabeth Catlett never knew her father, a Tuskegee Institute math professor who died before she was born, but a small wooden bird sculpture he left behind gave wing to the artistic interests that would ultimately define her career. Born near Washington, D.C., in 1915, grandchild of formerly-enslaved people, her life’s work would give poignant voice to the dignity, pride, strength, and hard-won victories of Black women in a society dominated by white men.

It was a society that was particularly cruel to artists of color. Very few Black women were working artists and art museums in the segregated South were off-limits to African Americans. But Catlett’s determination and vision were driven by strong advice she received early in her arts education: focus on and create art about what you know best. Having grown up on her grandmothers’ stories of life in slavery, she set out to express Black women’s experiences in sculpture, prints, and paintings. And she would go on to become one of the most important American sculptors and printmakers of the 20th century.

Catlett graduated from Washington’s Dunbar High School in 1931. The first public high school for African Americans in the District of Columbia and the United States, it was founded in 1870 as the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth. Early in the 20th century, it was renamed for the first nationally-recognized Black poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar.

College admission rescinded

She enrolled on a scholarship at the Carnegie Institute of Technology only to have her admission rescinded when the school learned she was Black. Instead, she enrolled at Howard University, her tuition paid with scholarships and the savings of her mother, a teacher. In 1935, she graduated cum laude with a degree in art.

But because the idea of a Black woman becoming a successful working artist seemed out of reach in the 1930s, Elizabeth Catlett followed her mother’s path and moved to North Carolina to teach. She taught art for two years in North Carolina’s public schools, where she worked with Thurgood Marshall in a campaign to win equal pay for Black teachers. But when that effort failed, she reconsidered her options, choosing to leave the classroom and pursue graduate studies in art at the University of Iowa.

The Grant Wood Years

Despite being accepted, Catlett found herself barred from living in the dormitories because of her race, so she had to rent an off-campus room. She graduated in 1940, one of three students — and the first Black woman — to earn the first Masters in Fine Arts from the university.

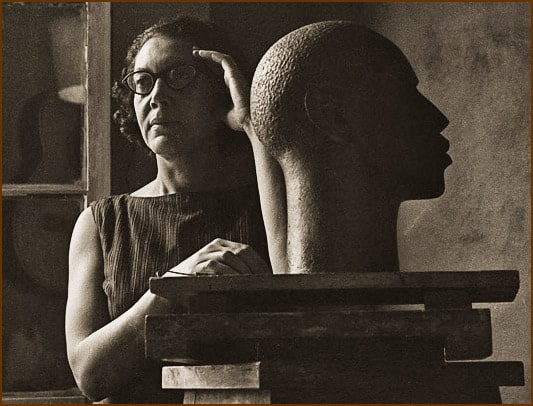

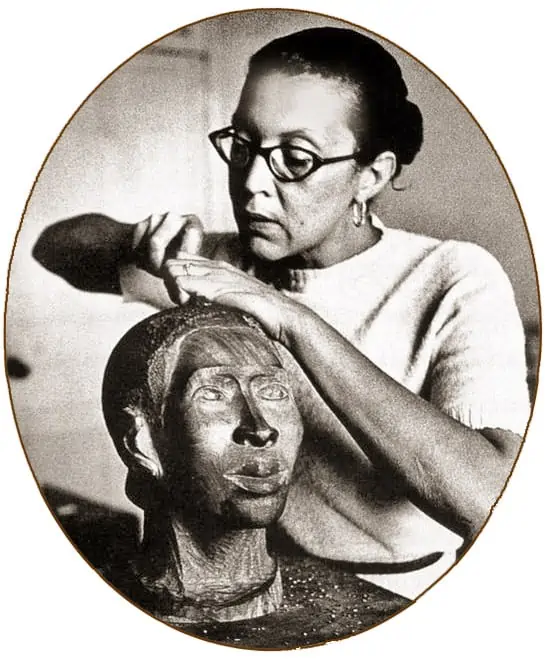

But it was there she met painter Grant Wood, perhaps best known for his painting America Gothic. He mentored Catlett, who soon turned her attention to sculpture. Wood encouraged her to experiment with different mediums to create lithographs, linoleum cuts and sculpture in wood, stone, clay and bronze. He was also the one who advised her to focus on what she knew best, so she began sculpting images of Black women and children. His advice paid off. The centerpiece of Catlett’s thesis exhibition was a limestone carving titled Negro Mother and Child. Now lost, her work captured the First Award in Sculpture at Chicago’s 1940 American Negro Exposition (also known as the Black World’s Fair).

New Orleans, Chicago and Harlem

For the next two years, Catlett taught drawing, painting, printmaking, and art history at Dillard University in New Orleans. Former students, most of whom had never been to an art museum, described her impact on them as “transformative.” Determined they see a major Picasso exhibit at a nearby museum closed to African Americans, she had students bused to the museum’s entrance on a day when it was closed to the white public.

Her next couple summers were spent in Chicago. She lived with the founders of the South Side Community Art Center, studying ceramics and lithography before resuming her work in sculpture. For the first time, she was part of a community of politically active artists dedicated to use art for social change.

She then married and moved to New York. It was in Harlem, in the 1940s, where she met artists and intellectuals like Gwendolyn Bennett, W.E.B. Dubois, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas and Paul Robeson. But more importantly, she taught adult education classes at the George Washington Carver People’s School — a night school for Harlem’s working-class people. Seeing for the first time how her students’ lives were shaped by their limited access to education brought her own privilege, thanks to her education and her class, into sharp focus and she was deeply moved by what she called the “cultural hunger” of the women she taught and with whom she worked.

A Sears, Roebuck Connection

Those women inspired her to apply for a Julius Rosenwald Fund Fellowship to produce a series of works (prints, paintings and sculptures) on the theme “The Negro Woman.” When her funding was renewed for a second year, Catlett realized she had to leave New York to complete the work she had proposed. Chartered by Sears, Roebuck and Company magnate Julius Rosenwald, the fund concentrated on equalizing opportunities among Americans, including funding schools for Blacks in the rural South. By the time the fund was dissolved in 1948, over $22 million had been awarded to hundreds of African American writers, educators, artists and scholars.

Having long been interested in post-Mexican Revolution art, Elizabeth Catlett and her husband went to Mexico in 1946. After several months, Catlett returned to the United States just long enough to dissolve her marriage, returning to Mexico on her own to establish a permanent residence.

Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Print Workshop)

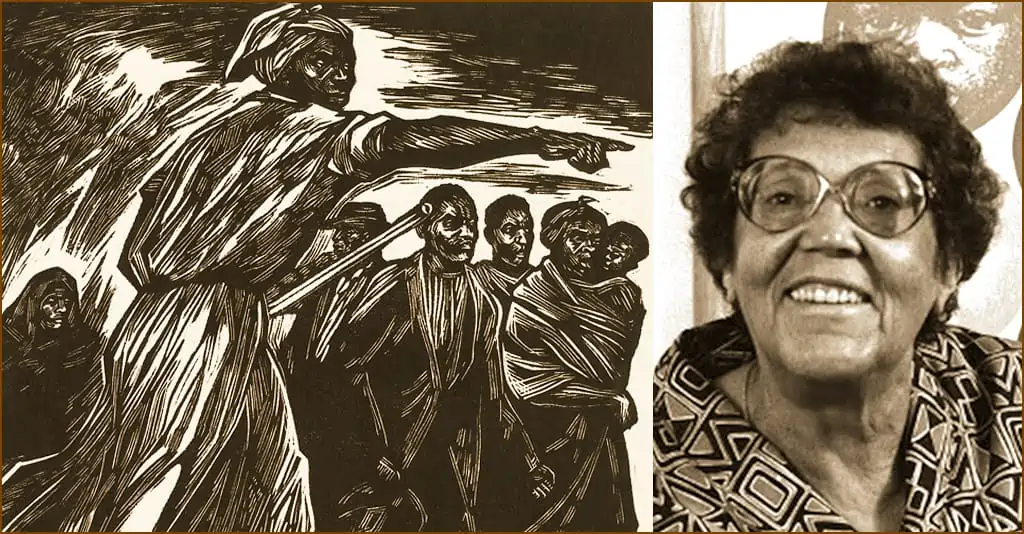

She soon found community with the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico City, a workshop dedicated to creating sociopolitical art whose beliefs meshed with her own — that to serve the people, art must reflect their social reality.

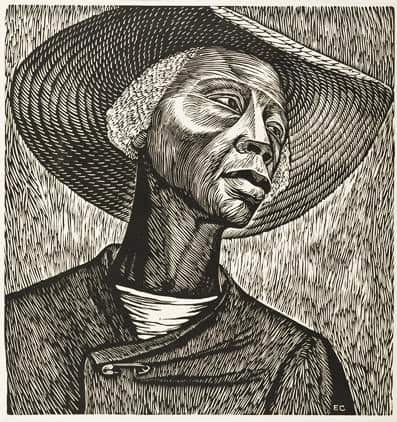

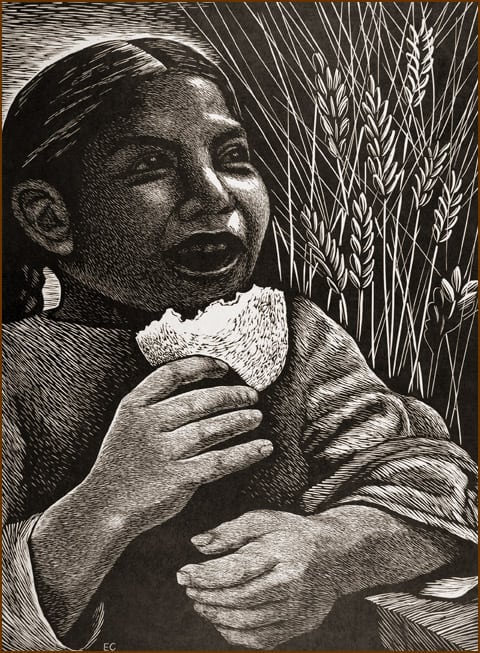

Prints, especially linoleum cuts, became Catlett’s perferred medium. From 1946-1947 she produced a series of 15 linocuts depicting the harsh reality of Black women’s struggles, from historical heroines to the fears and struggles of everyday African American women. Her 1952 Sharecropper is one of her most iconic works — from the woman’s tired eyes to her broad-brimmed straw hat and safety pin holding her jacket closed, all suggesting the hardships of her life.

She married fellow printmaker/muralist Francisco Mora in 1947 and they raised three sons. Becoming immersed in Mexico’s life and culture, she realized how similar Black and Mexican people’s histories and lived experiences were as she learned about “mestizaje,” or the blending of indigenous, Spanish and African ancestries shared by so many Mexicans.

Escuela Nacional del Artes Plásticas (National School of Fine Arts)

She returned to her love of sculpture in 1955 and, three years later, became the first female sculpture professor at the Escuela Nacional del Artes Plásticas, part of Mexico’s national university. Her appointment was immediately challenged by male colleagues who argued that she was (1) a woman, (2) a foreigner, (3) would only teach African sculpture and (4) that she was inept. Catlett ultimately won their respect and taught at the university until she retired almost 20 years later.

Barred from Her Own Country

Elizabeth Catlett continued her work with Taller de Gráfica Popular into the 1960s. It was an environment that supported her growing political activism. Some of its members were part of the Communist party, and Catlett’s support of a railroad strike in 1959 led to her arrest. Eventually, she was targeted by the United States Embassy and barred as an “undesirable alien” from entering the U.S. In 1962 she chose to renounce her American citizenship and became a Mexican citizen.

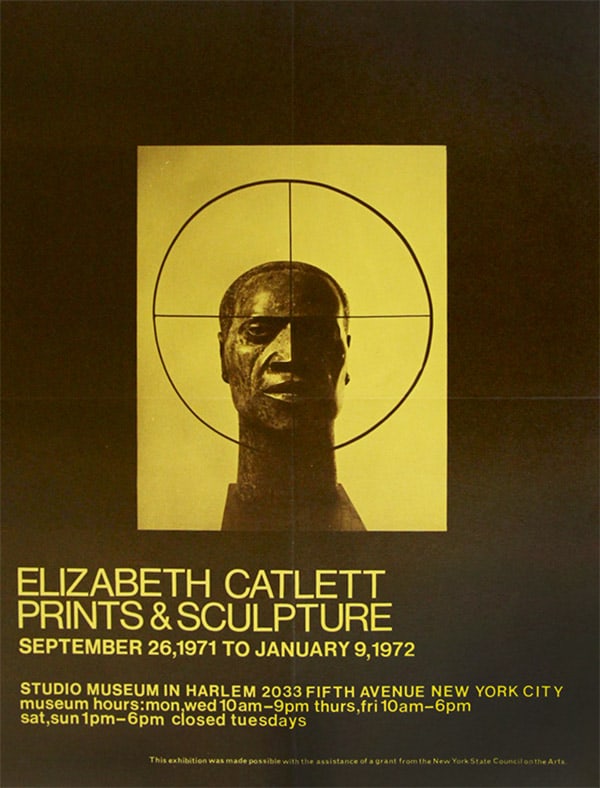

It was not until 1971, after a successful letter-writing campaign to the State Department by colleagues and friends, that she was granted a special visa to attend the opening of her solo show at Harlem’s Studio Museum. Though banned from her own country for almost a decade, her work during that turbulent time proclaimed solidarity with the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, focusing on the roles of women.

The Later Years

After leaving her position at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in 1975, she and her husband retired to Cuernavaca so she could devote more time to her art. But they also kept an apartment in New York City. She eventually regained her American citizenship in 2002, giving her dual citizenship.

Over her lifetime, Elizabeth Catlett received numerous awards and honors. A member of the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana (Hall of Mexican Fine Art), she received the Art Institute of Chicago’s Legends and Legacy Award and the International Sculpture Center’s Lifetime Achievement Award for contemporary sculpture. And she was awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts from Carnegie Mellon 76 years after it withdrew her scholarship for admission because of her race.

In 2006, the University of Iowa’s curator of European and American art visited Catlett in Cuernavaca and purchased 27 prints for its collection. Catlett donated proceeds of the sale to the University of Iowa Foundation to endow the Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship fund to support African American and Latino students in their study of printmaking. Today, the woman who was once barred from living in that university’s dormitories has a residence hall named in her honor.

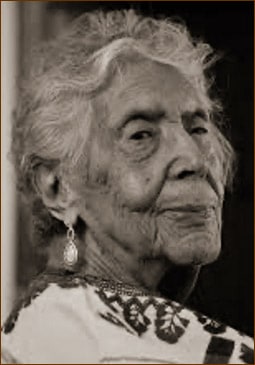

An active artist right up until her death, Catlett died peacefully in her sleep at her home in Cuernavaca in 2012 at the age of 96. Per her wishes, she was cremated in a private ceremony; her ashes, given to a family friend, remain in Mexico.

Legacy

Today Elizabeth Catlett is considered one of the most important American sculptors and printmakers of the 20th century.

She had known discrimination all her life: She was Black; she grew up poor; she was female; and she was targeted as an “undesirable alien” by her own government. But she never compromised her art and what it stood for. She once said, “I felt my work should do something for women because nobody was interested in them.”

Her work portrayed strong, dignified Black women as she brought expression to their careworn faces and focus to the respect Catlett felt they deserved. They had broad hips, broad shoulders and angular faces. And whether they stood with fists in the air or were nursing babies, their faces were often carved at an upward-looking angle that forced viewers to look up at them in a perspective that made them seem larger than life, like the real-life heroines they were.

Elizabeth Catlett was a feminist and an activist who pursued her career against all odds but freely acknowledged her contributions when it came to influencing younger African American women. There was a time when becoming a Black female sculptor “was unthinkable … There were maybe five or six Black women sculptors and they all had very tough circumstances to overcome. You can be Black, a woman, a sculptor, a printmaker, a teacher, a mother, a grandmother and keep a house. All you have to do is decide to do it,” she said.

Great article!!!!!!! Elizabeth Catlett and William Tolliver were the two most versatile artists if all time as well as two of the greatest artists of all time.