One of eight children born to a family of Mexican-American journalists and social activists in Laredo Texas in 1885, Jovita Idár went on to make her mark as a crusader for civil and women’s rights in a border region notorious for the racist and misogynistic policies and practices of its ruling white culture.

Idár learned early on about civil rights. And with access to a better education, and more opportunities than many Tejano families who settled in South Texas long before the modern border with the United States was established in the 1840s, she was driven by a desire to improve conditions for others.

In 1903 she earned a teacher’s certificate from Laredo’s Holding Institute, founded along the Rio Grande in 1880 by the Methodist Episcopal Church. She took a teaching position in a little school in the town of Los Ojuelos, about 40 miles away that, today, is little more than a ghost town since a local oil boom went bust.

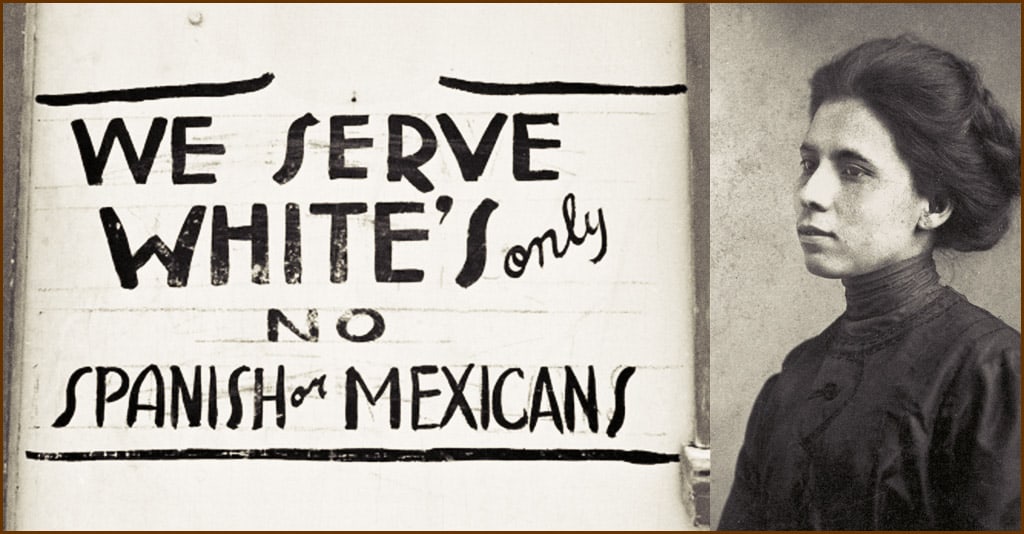

‘Juan Crow’ Laws

Once in the classroom, she came face to face with the realities of the dinner-table conversations she had grown up with. The same Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation infringed on the rights of Mexican Americans in South Texas; so much so that today’s scholars refer to them as “Juan Crow” laws. Signs reading, “No Negroes, Mexicans or dogs allowed” were common in stores and eateries. Schools were poorly funded and equipped. And speaking Spanish in public was discouraged.

As Robin Kadison Berson writes in Marching to a Different Drummer: Unrecognized Heroes of American History, “there were never enough textbooks for her pupils or enough papers, pens or pencils; if all her students came to class, there were not enough chairs or desks for them.” Frustrated, Idár realized her efforts at teaching made little impact on children’s lives in such poorly-equipped, segregated, rundown schools.

Newspaper reporter

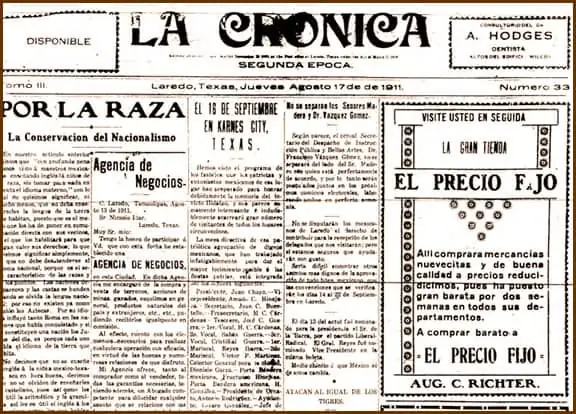

Believing she could channel her activism into journalism as a means for more meaningful change, she gave up teaching and came home to Laredo to become part of her father’s newspaper, La Crónica (The Chronicle), a major voice for Mexican and Tejano rights. In addition to biographical, historical and literary essays and poetry, La Crónica ran stories on education inequality, discrimination against Mexican Americans, poor economic conditions and the loss of Mexican culture.

It was there, against the backdrop of the decade-long (1910-1920) Mexican Revolution, Jovita Idár began writing exposés about Mexican American workers’ poor living conditions. Using pen names like Astraea (Greek goddess of justice) and Ave Negra (black bird), she also wrote about equal rights for women, encouraging female readers to educate themselves and become less dependent upon men.

Lynchings

But this was a period when the lynching of Mexican men hit an all-time high as Mexican Americans sought to advance their education, promote their culture and fight for their civil rights. In 1911, after the brutal lynching of a 14-year-old boy, a group of Mexican Americans gathered in Laredo seeking solutions. That meeting, led by the Idár family, was known as El Primer Congreso Mexicanista — the first Mexican American Civil Rights meeting — a group of Mexican Americans who wanted to fight for fair and equal treatment of Hispanic people in Texas.

At the same time, Jovita Idár co-founded and became the first president of La Liga Femenil Mexicanista (the League of Mexican Women). One of the first known Latina feminist organizations, its mission was to provide free education to Mexican children in Laredo. La Liga believed borders shouldn’t separate women, since Mexican and Mexican American women had the same needs and wants. Members crossed the border, sharing their message in Laredo, Texas, and Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. They created study sessions for women, opened free bilingual schools for children, and raised money for poor families; promoted financial independence for female workers, and encouraged them to join the feminist movement.

Both El Primer Congreso Mexicanista and La Liga Femenil Mexicanista took as their motto, Por la Raza y Para la Raza — For the Race and By the Race.

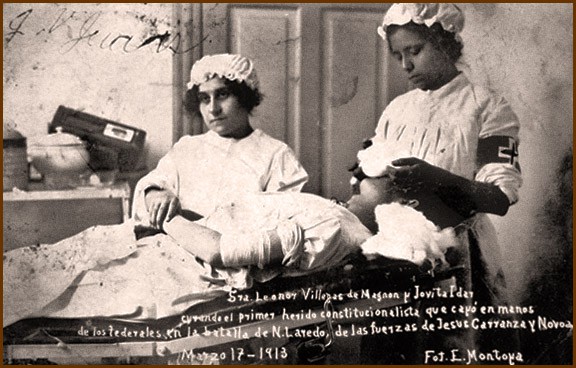

War-time nurse

By 1913, the Mexican Revolution’s Battle of Nuevo Laredo raged just across the Rio Grande from Idár’s home. With Mexican American women drawn to the revolutionaries’ cause, Idár and her friend, Leonor Villegas de Magnón, founded La Cruz Blanca (The White Cross) — a relief agency similar to the American Red Cross, and helped Mexican American women cross the border to volunteer as nurses. Idár and her volunteers traveled as far as Mexico City in their support of the revolutionary army.

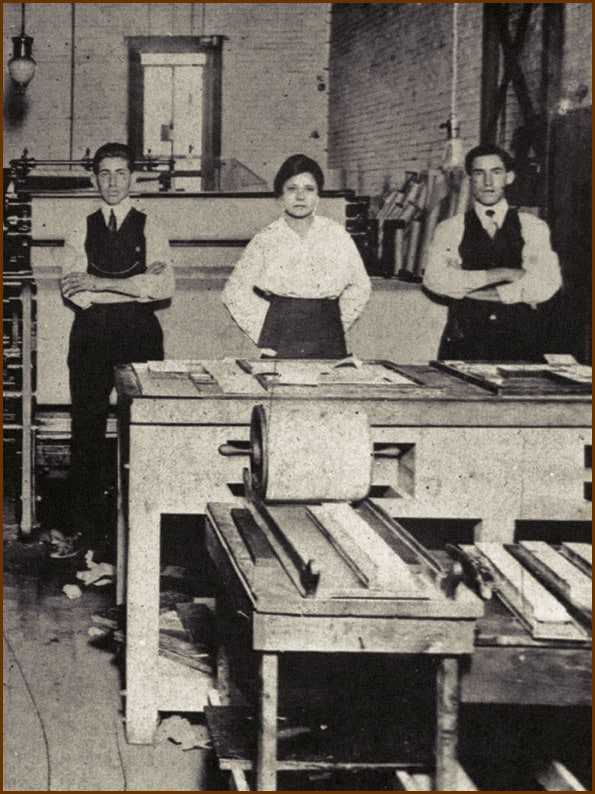

Upon her return from volunteer nursing, she began writing for the newspaper El Progreso (The Progress). An op-ed piece that took issue with President Wilson’s order to send U.S. troops to the southern border didn’t sit well with either the U.S. Army or the Texas Rangers who, at the time, served as a police force protecting Anglo Texan economic and political elites — shooting first and asking questions later. When they showed up one day under the governor’s orders to close El Progreso, Idár wasn’t having it.

Confronting a mob

Her argument against a group of white men with a reputation of violence against Mexicans was simple: silencing her newspaper violated its constitutional right to freedom of the press under the First Amendment. She single-handedly blocked the entrance to the newspaper’s office. But when they returned the next day, with Idár out of the office, they ransacked it, destroyed the presses, and effectively put an end to the newspaper.

With the death of her father in 1914, Idár became editor and senior writer at La Crónica, continuing to expose the conditions and inequalities under which Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants lived. Two years later, she founded the weekly paper Evolución, which she ran until 1920, when she turned it over to one of her brothers.

By then, she had married and moved to San Antonio with her husband, where the couple founded El Club Demócratica within their local Democratic party and became community activists and political leaders. Idár also returned to her teaching roots, establishing a local free kindergarten while volunteering her time as a Spanish-language interpreter at a local hospital. She was also active in helping undocumented workers obtain naturalization papers after the Border Patrol was created in 1924.

An unknown hero

Jovita Idár died at her home in San Antonio in June of 1946 at age 61. Having suffered from advanced tuberculosis, her cause of death was pulmonary hemorrhage. By the time of her death, very few people knew about her remarkable history as an educator, journalist, civil/human/women’s rights activist, and her work during the Mexican Revolution.

But times have changed. Since her death, Jovita Idár was profiled at the National Women’s History Museum; in the Women in Texas History series; in the 2005 edition of The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States; and in the series Texas Originals. She was included in the 1996 publication, Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage that includes Laura Gutierrez-Witt’s “Cultural Continuity in the Face of Change: Hispanic Printers in Texas.” And in 2018, Gabriela González’s Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability and Rights described the role of Idár and her family in political activism over several generations.

Today, if you visit Laredo’s St. Peter’s Plaza, you’ll find a historical marker honoring Idár’s life and legacy; her home town even renamed its soccer complex Jovita Idár’s El Progreso Park in 2019, four years after the marker was placed. And in a nod to the times, a Google Doodle honored Jovita Idár with a depiction of her famous blockade of El Progreso as part of Hispanic Heritage Month on September 21, 2020.

Today we know who Jovita Idár was. As an educator and activist, she believed in the cultural redemption of “la raza” — a term used to refer to Mexicans and other Latinos, understanding that education and empowerment were key to uplifting poor communities on both sides of the Rio Grande. And as a journalist and suffragist, she kept the focus of her writing on racism, women’s rights, segregation, poverty, bilingual education, anti-Mexican fervor, and access to democratic institutions — issues still very much in the news today.