As a little girl born in Budapest, Ágnes Keleti dreamed of becoming a cellist. Instead, she saw her father deported to Auschwitz, escaped the Nazis using forged identity papers and, ten years later, became one of the greatest Olympian gymnasts of all time and the most successful Jewish female athlete in the history of the Games.

Born in 1921 to a Jewish Hungarian family, Ágnes Keleti’s father enrolled her in gymnastics at Budapest’s Jewish Club when she was four years old. By age 16, she was Hungary’s National Gymnastics Champion, looking forward to competing in the 1940 Olympic Games. But as World War II raged throughout Europe, Keleti’s plans, along with the 1940 and 1944 Games, were derailed.

Lost father to Auschwitz

Expelled from her gymnastics club with all the other non-Aryan athletes in 1941, she found herself in desperate straits. The Keletis lost their home; the family was separated and forced into hiding; and, in 1944, her father was deported to Auschwitz, where he and other close family members perished.

During Germany’s occupation of Hungary, Keleti survived by buying forged identity papers and posing as a Christian girl named Yuhasz Piroshka. She worked in a munitions factory, in the fur trade, and even hid in plain sight as a housekeeper in the home of Budapest’s Nazi-sponsored deputy commandant. But Keleti’s most harrowing job, during the 1944-45 battle for Budapest, was making morning rounds to collect the bodies of those who had perished the day before and transport them to mass graves. To this day, she wonders aloud, “Is it possible to forget such a thing?”

Mother and sister saved

In another part of Budapest, Keleti’s mother and sister were also in hiding, eventually saved by Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who rescued thousands of Jews by issuing Swedish “protective passports.” Once a week, Keleti smuggled bits of leftover food to her sister and mother. They were among the lucky ones — of the 800,000 Hungarian Jews in 1941, only about 25% survived the Holocaust.

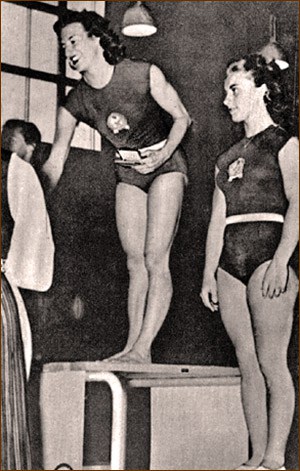

When the war ended in 1945, Keleti returned to gymnastics, taking center stage in international competitions from 1947 to 1956, But just days before she was due to compete in the 1948 London Olympic Games, 24-year-old Keleti tore a ligament in her ankle. On crutches, she watched from the sidelines as the Hungarian gymnasts placed second behind Czechoslovakia.

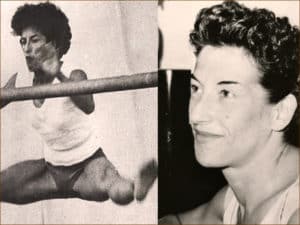

Her next chance to compete on the world stage came at the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games. It was the first Olympics to feature individual gymnastics events for women. And Ágnes Keleti was 31 years old — ancient in the world of gymnastics. She recalled being cool as a cucumber and remarkably laid back: “I didn’t really think I could win anything, but I was traveling and getting the chance to see the world.”

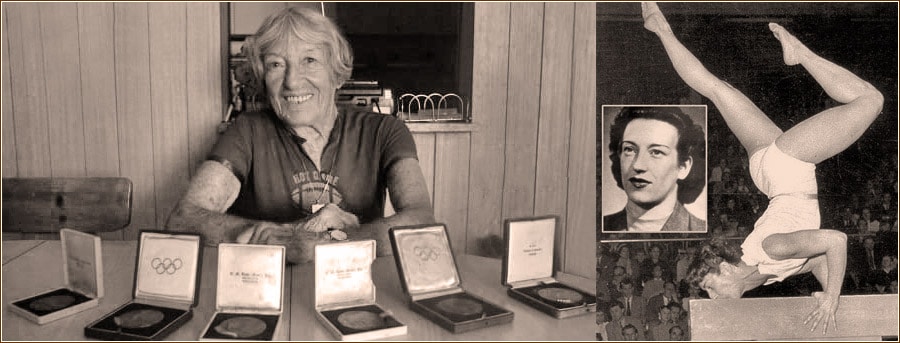

Four Olympic medals in 1952

Keleti surprised everyone, herself included, by winning four medals — a gold for her floor exercise program, a silver in team competition and two bronze medals for uneven bars. But she wasn’t done yet. In fact, this tiny “geriatric” gymnast was just getting warmed up. She had her sights set on Australia’s 1956 Melbourne Games.

But by Fall of 1956, public unrest and discontent in Hungary had escalated into open revolt against the ruling Communist Party. The rebels declared victory as Hungary appealed to the United Nations for backing. But as the West dithered, shying away from another global confrontation, the Soviets pounced, invading Hungary and successfully quashing the revolution.

Two weeks after the rebel uprising, Keleti and the Hungarian delegation left for the Melbourne Games. The pinnacle of her gymnastics career would also prove to be her last Olympics. At age 35, she won six Olympic medals — four golds and two silvers. Her showing made Ágnes Keleti the top medalist of the 1956 Olympiad and the oldest female gymnast to ever win gold.

Hungarian uprising

It was during the competition Keleti learned her country’s anti-Communist revolution was put down by the Soviet Union, leading her and 47 other Hungarian athletes to make a life-changing decision. They opted to defect to the West, Melbourne’s Hungarian community providing them with money, jobs and safe places to live while they applied for political asylum.

Keleti spent about nine months in Australia, working in unsatisfying jobs, until an Israeli diplomat sought her out with an invitation to take part in the 1957 Maccabiah Games — an international Jewish athletic competition similar to the Olympics. Arriving in Israel, she immediately felt at home. “I didn’t want to be a Jew in Hungary,” she recalled. “I wanted to be an Israeli in my own country.” She sent for her mother and sister, married in 1959, and retired to raise her two sons.

Revamped Israeli gymnastics training

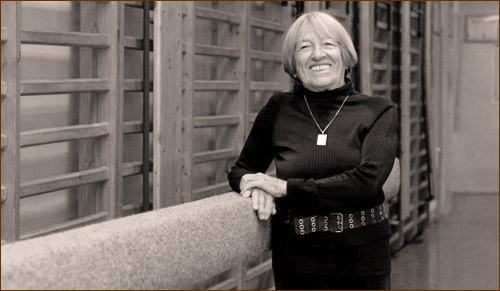

Though no longer competing, Keleti taught phys-ed at Tel Aviv University and, for 34 years, at the Wingate Institute for Sports. She also started coaching Israel’s national women’s gymnastics team, working with young athletes well into the 1990s, bringing in new training equipment and restructuring the way Israeli gymnasts trained. Described as “an object of admiration and awe among the girls and other coaches,” Keleti is recognized as the keystone of gymnastics in Israel.

In January of 2019, Ágnes Keleti celebrated her 98th birthday. Two years earlier, she was the subject of an interview during which she happily answered questions upside down from a handstand position, throwing in some handsprings and splits for good measure.

10 Olympic medals

Over her long, remarkable career, Ágnes Keleti won 10 medals from three Olympic Games, making her the third all-time among women for the most Olympic golds, and fourth all-time as an overall Olympic gold medal winner. A member of the Hungarian Sports Hall of Fame, she represented Hungary 24 times in international competition. Keleti is a member of the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame, the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and, in 2002, entered the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame as the most successful Jewish female athlete in Olympic history.

But despite all the medals and public accolades, Keleti remembers the tiny five-year-old girl who preferred practicing and playing the cello to tumbling and turning cartwheels. In a 2005 interview with the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, she grew wistful, citing a long-ago dream. “After everything got lost, my entire home,” she recalled, “I didn’t play anymore. The cellist died at age 18, when they took everything from us.”

During a 2012 interview, Ágnes Keleti found herself digging through cabinets, cupboards and drawers in her apartment, looking for her medals, before realizing she had misplaced them. No matter. As the plucky Holocaust survivor considered her gymnastic glory days and dedication to her sport, she explained, “Staying alive is more important than the medals. The medals have no meaning.”